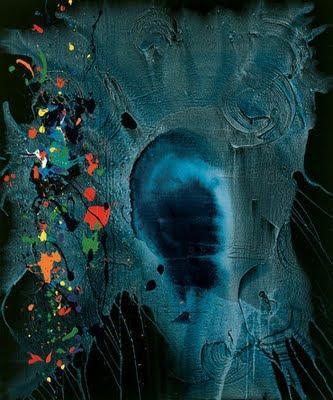

Love and Grief by John Holland*

I will be 65 in August. I started doing yoga when I was 18 in 1970 using the black and white pictures in an old paperback copy of Richard Hittleman's book as a guide. Even given lengthy breaks, I have practiced yoga for more than 40 years, mostly on my own, supplemented periodically with classes and several private sessions. And I practiced yoga two to three times a week with a wonderful teacher throughout my second pregnancy in 1986 with my son, Maxx. He was my "yoga baby."The shock and trauma of Maxx’s diagnosis, illness, and ultimate death from T-Cell Lymphoma in 2007 at the age of 21 was completely unexpected, swift, and utterly annihilating to all of us. Diagnosed on July 11, dead on December 6th—one day a healthy, vibrant, funny, intelligent college junior looking forward to the rest of his life and just 17 weeks later, after physically and emotionally undergoing grueling treatment, gone from this world.

I felt that my life was over. Being on this planet without my son was unimaginable. I wanted no part of it. I continued to work full time only because I had to, but beyond basic household tasks and the rare outing to a movie or a visit with my daughter, I was psychologically immobilized by anxiety, remorse, guilt, and fear. A full year passed before I was able to return to intentional physical movement in the form of deliberate exercise, something I had done regularly all my life and an interest that Maxx and I had shared and enjoyed together. My first effort was to return to my stationary bike. Pedaling and often crying, I started with 10 minutes a night. Soon thereafter, I was able to lie on my back, legs propped up against the wall, arms stretched out to either side. Slowly, I began to add back some of the familiar poses I had practiced several evenings a week before he became ill.

My practice was halting, abbreviated, a haphazard mix of soothing, improperly aligned poses. My body was stiff with sorrow and non-use, any former flexibility gone. My spirit so flattened, sometimes I couldn't even bring myself to the mat unless I'd had a glass or two of wine—an approach I called "Drunk Yoga." But my practice was becoming more consistent and I continued.

I was unable to sit for any form of breathing meditation because quietly focusing on the sound of my breath was an excruciating trigger for a panic attack. We had watched Maxx struggling for air just before he had been intubated only hours before he died. The memory of him lying in a coma, a ventilator down his throat, precluded me from taking a conscious cleansing breath for the next eight years.

Now, ten years later, I still practice yoga, though much has changed in my approach. Early on in my grief, I mistakenly believed yoga would prove to be a way "out" or "through." The only time I was ever able to find a few moments of respite was when I was moving or resting in a yoga pose. I developed a short series of floor poses that seemed to calm me—all were essentially restorative in nature.

During this time I also took medication for anxiety and depression (still do), was in various forms of talk therapy, read, wrote, and tried in whatever fashion I could to find a life of some sort after losing my son. Yoga played its part, but yoga was not—could never be—a panacea for either the grief or intense anger I felt. In fact, I feel that the current emphasis on yoga for grief—meaning in the past decade—is misleading and ultimately deeply disappointing for anyone encouraged to think it is a way “out.” Grief for a lost child or a beloved other is a pain that one carries for a lifetime. There is no "out." There is no "through." We ultimately learn ways to shoulder the burden, to live with the weight of our sorrow. A regular practice seems to allow time and space for that lesson.

As with most ideas or concepts that "trend" in our popular culture, yoga in the mainstream has become a particularly lucrative market for studios, teachers, fashion, authors, businesses, and health-care entrepreneurs of every type. It is touted as solution for everything from alleviating back pain to promoting world peace. In many ways, yoga has become a snake oil for our time. Caveat Emptor. My point being that the bereaved are an extremely vulnerable population.

We are prone to reach for anything we think will give us some momentary respite from the agony of loss. Yoga can, and does, help. For some, practice can become an entire lifestyle with far reaching effects. In my own experience, however, yoga was not the only approach to finding a life after losing my son. Rather, it is one of many choices for activity that I have attempted to cobble together in the last nine years. find that both practicing and learning about yoga is more beneficial in smaller, more digestible doses. Too much of anything, too quickly, is counterproductive and anxiety provoking.

So it is important to remember that the experience of grief and the manifestation of sorrow are unique to the person, specific to circumstances, and dependent upon so many variables as to be impossible to categorize or mitigate.

Despite my reservations, I can say that yoga (asanas and breath work) has had a positive effect on my state of mind. This takes different forms and can occur both during the practice and on my moods long after. I am a realist. My practice is what works for me given my own temperament and my own experience. I offer these few suggestions in the hope that others may benefit.

My poses are primarily seated and I emphasize any hip-openers as well as shoulder and back stretching, as that is where I hold my tension. I move very slowly, breathing as deeply as possible. I do not force or push my body, and my motions are never vigorous. Powerful, yang-type asanas make me anxious and seem counter-intuitive to my needs, which are for extended, calming movement and breath. My flow is ad hoc, extemporaneous, flexible. I try to follow the sensations in my body, which will let me know what to try first and what comes next.

In addition to these yoga movements, I also ride a stationary bike every evening for 30 minutes and do light hand weights to strengthen my upper back muscles and improve my posture. The bereaved tend to hunch imperceptibly forward (over their hearts) as the years pass in an unconscious broken posture of self-defeat.

The combination of all three kinds of movement has admittedly been very helpful when I am experiencing some of my deepest sorrow. I did the same few poses over and over again with little variation. The sameness of the routine itself was comforting. Now, I am able to more easily change the sequences, add new poses, and remove others. Essentially, I do what feels best in no particular recommended order, but according to what my body seems to be requesting at the time.

- Cat/Cow Pose: Breathing appropriately and very slowly (several times to loosen low back). See Featured Pose: Dynamic Cat-Cow Pose.

- Dynamic Downward-Facing Dog: Moving in and out of Downward-Facing Dog pose with my breath from the all-fours position or from Cat pose, repeating a few times.

- Lunge Pose (Vanarasana): Both high version and low version, with back knee on the ground. See Featured Pose: Lunge Pose.

- Child's Pose (Balasana), with arms extended: Hold for several seconds. See Featured Pose: Child's Pose.

- Reclined Arms Overhead pose (Supta Urdva Hastasana): Breathing slowly in three-part breath, stretching as much as I can into shoulders.

- Thread the Needle Hip Stretch: See Opening Your Hips Without Knee Pain. Friday Q&A: Opening Your Hips without Knee Pain.

- Reclined Leg Stretch (Supta Padangusthasana), all three versions: Leg straight up, out to the side, and twisting. See Featured Pose: Reclined Leg Stretch.

- Wide Angle Seated Forward Bend (Upavista Konasana) and Sideways Wide Angle Seated Forward Bend (Parsva Upavista Konasana).

- Frog Pose (Mandukasana): For an inner thigh stretch.

- Legs Up the Wall Pose (Viparita Karani), with no support. See Featured Pose: Legs Up the Wall Pose.

- Gentle Twists: Any kind, seated or reclined.

I will also practice in a reclined position once in awhile. In both poses I will occasionally place one hand on my heart and one on my belly. This calms me and helps me to concentrate on breathing in and out slowly. It feels reassuring to feel pressure in these two areas. Frequently, I listen to tonal meditative music. I am easily aroused and agitated by any noise, and find that listening to this type of music helps greatly in facilitating concentration.

I believe that people who are grieving, or suffering from any intense emotional distress can eventually be open to, and will try, in small steps and with gentle persuasive nudges to move in the direction of something that offers a non-competitive, non-judgmental, accepting opportunity to turn down the volume of despair. I think yoga allows for this flexible, individual approach.

Though I am not a teacher, a celebrity, or an expert, it is likely that I am representative of the majority of grievers who simply must find ways to survive after suffering great loss. I am a proletariat practitioner in the front line trenches and as such, I believe my own experience to be as valid as any "grief expert"—possibly more so.

Lisa Wendell is originally from Southern California, and she moved with her husband, Steve, and their children, Megan and Maxx, to the San Francisco Bay Area in 1986. Recently retired from her position as the Acquisitions Director in the library of a private university, she is hoping to take more time to write, exercise, read, garden and develop her yoga practice. Since the death of her son in 2007, she has devoted singular and concentrated effort toward accepting, understanding, and living with the significance of her loss.

Subscribe to Yoga for Healthy Aging by Email ° Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook ° Join this site with Google Friend Connect