If you have been around the yoga classroom for any reasonable amount of time, you have likely heard of the psoas muscle. But you may not have a good idea of where it is or what it does! You should though, as your daily activities—or inactivity if you are sitting a lot during the day—can actually create a short, tight psoas muscle that could use a bit of lengthening. So today I’ll introduce you to your psoas muscle in a deeper way than can sometimes take place in the yoga classroom, inform you of some of its roles in posture and movement and suggest a few ways to lengthen it, if it is on the tighter side of life.

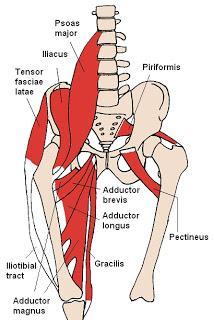

The only other time I could find on the blog that we had talked about the psoas muscle was way back in January of 2012 (I Think I Have Sciatica), where we first introduced this drawing of the lower torso and pelvis which shows nicely the psoas muscle seen here with everything except the skeleton and select muscle removed.

The psoas is said to originate from the sides of the lumber vertebrae, possibly even starting as high up as thoracic 12 (T12), so it has multiple spots on the side of the spine where it attaches. It then travels downward, close to the midline of the pelvis, just in front of the sacrum and ileum, until it heads slightly lateral and anterior, so it can leave the pelvis by sliding right over the lateral pubic bone and just behind the inguinal ligament in order to dive down and laterally attach to the upper inside of the femur bone (at a bony bump known as the lesser trochanter of the femur). Now we can actually feel the greater trochanter with our hands, just about six inches below the side of our pelvic rim, but the lesser bump is not accessible - due to lots of muscles which make touching it almost impossible. And due to the fact that the psoas lies deep within the pelvis, it can be challenging to feel it - both literally and perceptually.

The psoas is said to originate from the sides of the lumber vertebrae, possibly even starting as high up as thoracic 12 (T12), so it has multiple spots on the side of the spine where it attaches. It then travels downward, close to the midline of the pelvis, just in front of the sacrum and ileum, until it heads slightly lateral and anterior, so it can leave the pelvis by sliding right over the lateral pubic bone and just behind the inguinal ligament in order to dive down and laterally attach to the upper inside of the femur bone (at a bony bump known as the lesser trochanter of the femur). Now we can actually feel the greater trochanter with our hands, just about six inches below the side of our pelvic rim, but the lesser bump is not accessible - due to lots of muscles which make touching it almost impossible. And due to the fact that the psoas lies deep within the pelvis, it can be challenging to feel it - both literally and perceptually. Hopefully, with the help of the picture and my written description, you are starting to get oriented to where the psoas is. But what does this muscle do when it contracts and shortens? It depends a bit on which part of the set-up is stabilized and which part is free to move. And it also depends on whether it is working in concert with other muscles to help you walk (for instance), or to help you maintain upright posture when you are standing still.

Let’s look at it working alone first. If the spinal origins of the psoas are stable and not moving, the psoas is said to have the following effect on the femur bone (to which it attaches): it flexes the femur toward the belly, pulling it slightly medially toward the pubic symphysis, and rolls the thigh bone externally on its axis. If we wanted to take the femur bone in the opposite direction as a way of stretching it, we’d need to take it backward towards the buttocks, swing it slightly out to the side and internally rotate it. Doing a modified Locust pose (Salabasana), with the legs apart a bit and an emphasis on rolling the thighbones in would be an example of a pose that could lengthen the psoas.

When we stabilize the femur, as when you are sitting in a chair, and contract the psoas, the origin gets pulled forward and down, encouraging the forward folding action known as flexion of the lumbar spine. We use this action whenever we bend over to pick something up off the floor. The psoas also works in concert with several other spinal muscles to encourage the upward lift of the spine that we cultivate in poses like Mountains pose. In that setting, it does not create excessive lumber flexion, but does allow the natural curve in the lumber area to be present. So that is a bit about what the muscle does (realizing that the psoas works with other muscles that flex the femur bone, such as part of the quadriceps).

When the psoas is overly tight and short, it can affect the lower back in a negative way (contributing to back pain), influence the ease of a neutral pelvic tilt and affect gait. There are passive ways to release tension in the psoas and more active ways to lengthen and stretch the psoas.

In The Psoas Book, author Liz Koch recommends “releasing” tension in the psoas by lying in Constructive Rest position (on your back, with your knees bent and the soles of your feet on the floor), with your feet about 1-2 feet from your hips, and staying there for a while (maybe 5-10 minutes) with close attention to sensations in the area of the back belly and hip joints, as you attempt to sense the releasing of tension in those areas. Another version of Constructive Rest involves having your calves on a support, like our Easy Inverted pose (see Easy Inverted Pose). Once you get better at sensing release in tension in this area, slowly move one foot further away from the hips without letting the pelvis tip or tuck and stop when tension is encountered in the areas you are observing. Gradually moving that foot until the leg is straight, if you can do so without changing the pelvic alignment. A more advanced variation involves folding one leg into the chest (in an upside-down Pigeon pose), without tipping or tucking your pelvis, and then again slowly extending the other leg long on the floor (it’s the lengthening leg that will stretch that side's psoas).

In my regular classes, I often take advantage of the back leg position in Warrior 1 to bring attention to the psoas of the back leg, as it needs to lengthen in order to keep the pelvis neutral (not going into dramatic anteversion or forward tip). From there, doing drop knee lunges, both with the hands on the floor next to the feet for an easier version, but gradually coming up higher, with hands on blocks, and finally with hands on the front thigh, while letting the hips and torso move a bit forward while keeping the pelvis stable, are great ways to lengthen the psoas. The back leg in upright Pigeon pose also gives a good stretch to the psoas.

This list of ways to work with your psoas is by no means complete. You might look at Mary Pullig Shaztz, MD’s book Back Care Basics for her approach to psoas stretching in the face of back pain. And Jean Couch’s classic The Runners Yoga Book is sure to have a few suggestions as well. And if our readers have any favorites, please write a comment back to us! Happy stretching!

Subscribe to YOGA FOR HEALTHY AGING by Email ° Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook