We recently received this query from a reader about contraindications for spinal movements:

When are extension and flexion of the spine contraindicated. I have a patient who has issues with L5 and L6. I guess extension (backbends) would be contraindicated, correct? Also what about folks who have issues with inter vertebral discs? And what about people who have a hump in the cervical-thoracic region?

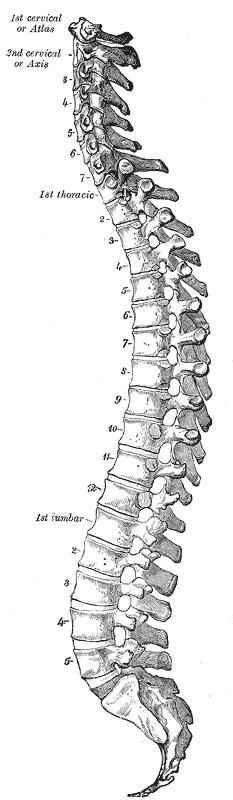

These are actually very complex questions but I will try to stay on track here. My previous post All about the Spine gave some background on how the spine changes shape in various movements, including forward bending, back bending, twists, and side bending. Now I like to think about the spine as a train where the head on the neck is the “engine, the subsequent vertebra are the train, and the coccyx is the “caboose.”

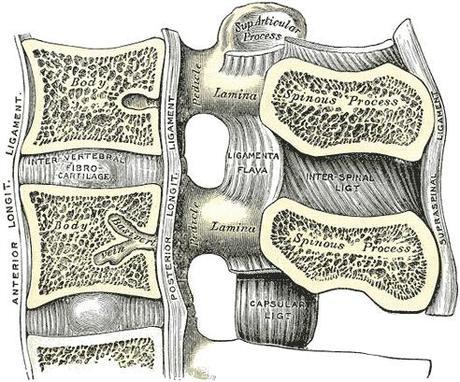

These are actually very complex questions but I will try to stay on track here. My previous post All about the Spine gave some background on how the spine changes shape in various movements, including forward bending, back bending, twists, and side bending. Now I like to think about the spine as a train where the head on the neck is the “engine, the subsequent vertebra are the train, and the coccyx is the “caboose.”All these separate vertebra are connected to each other by numerous ligamentous attachments. Anterior is a long ligament that runs down the front of the vertebra from C1-S1 and posterior is long ligament that runs down the back portion of the vertebra. This sandwiches the vertebra so they don’t slide forward or backward in relation to the individual top- and bottom-connecting vertebra. There are also many other types of connecting ligaments between different portions of the spine. Again, the function of all the ligaments is to keep the spine stable, and to allow coordination of movement but not too much movement at specific vertebral levels!

Anterior and Posterior Long Ligaments of the Spine

Now the interesting thing about ligaments is that they don’t have much stretch to them. In fact they don’t really stretch at all because they are stabilizing structures. What that means is that they limit movement in the spine. This is a good thing because since the spine houses the spinal cord, we really don’t want to tug or pinch our spinal cord because it is the main power house that connects our brain literally to our bones and muscles and allows us to move when and how we want to.Between each vertebra sits a cartilaginous structure called an intervertebral disc that is connected to both the top and bottom vertebrae. The discs are the shock absorbers of the spine and they absorb the motion at each vertebral level.

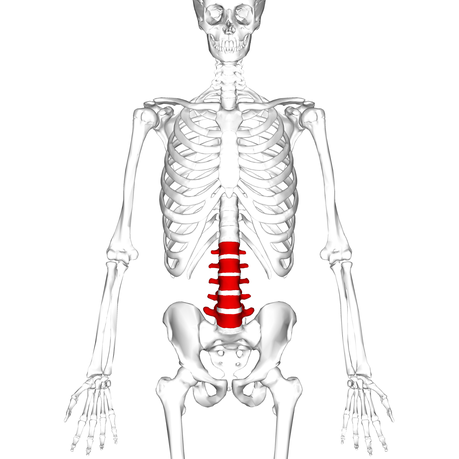

Lumbar Vertebrae (L1-L5)

Now lets talk about what happens when there is a problem at a specific vertebral level. We can have “cranky” backs and sometimes it doesn’t take a whole lot to have your back “go out” (actually I dislike this expression because the back isn’t going anywhere so it can’t really go “out”). However, there can be areas of the spine that are more sensitive to movement. The question asks about L5 and L6 specifically. Now there aren’t a whole lot of people who actually do have an L6. Typically we only have 5 lumbar vertebrae (L1-L5), and L5 is often injured or fragile in a lot of people from different causes.When there is a specific vertebral level that is injured, it is important to understand what the actual injury is because then you can understand how to take care of it so it heals.

There are specific spinal conditions where forward and backward bends should specifically avoided, including recent spinal surgeries, recent or acute disc injuries, or any acute injury where pain is a true warning sign not to proceed. For spinal instabilities like spondylolisthesis back bends should be avoided, and if you have facet arthritis of the spine in lower back or neck, backbends may aggregate this kind of arthritis pain. Also, with rheumatoid arthritis and other conditions where ligaments are adversely affected, all yoga postures will need modifications to avoid over stressing ligamentous attachments.

But specific level vertebral injuries can be challenging because you can’t just stop that area from moving Movement allows the intervertebral discs to get nutrition and hydration. When the spine is prevented from moving whether from medical intervention (like surgery) or wearing a rigid brace to prevent movement, sometimes the injured area heals but due to immobility a lot of other areas of the body aren’t very happy. When there is a disc injury, allowing some flexion and extension is encouraged but the issue is the degree of motion. So what you can learn to do is how to move without causing further injury.

When I say it is important to learn how to move, what I mean is that often when people do forward- or back-bending asanas, the movement isn’t well distributed along the spine and certain areas take more of the movement in an unhealthy way. When vertebrae are stiff or there is a particular loss of motion in one area, another corresponding adjacent area will move more to correct the motion loss. This isn’t a conscious action but the body learns how to make due with what happens. So if the L5 doesn’t move well then the vertebra above it, L4, will begin to move more to compensate for the loss of movement at L5, and S1 (the top of the sacrum) will also move more than it should to also compensate. This motion loss can occur anywhere along the spine and this is how problems develop, though certain areas are more predisposed to motion changes.

But in situation described by the reader (issues with L5 and L6), should the student practice forward and back bends? Well, there isn’t really a simple answer. Remember, the spine needs to move. So, the answer is yes, but with careful attention to form and detail. I like to think about making the movement long and soft, not short and tight. There is always a quality of “work” in every active asana, but the key is how much work is safe? There should never be sharp point specific pain and there should never be asymmetrical pain.

A passive backbend over a bolster or blanket roll (lying on your back with your knees bent using a bolster or a blanket roll perpendicular to the torso) to help change the upper back curve is beneficial as long as the neck and lower back are protected so they don’t arch too aggressively. Also, learning to relax as well as stretch the diaphragm are also helpful, which you can do with a gentle Cobra pose or supported Upward Bow (Urdhva Dhanurasana) with a chair. Another very accessible backbend for the upper back is Supported Bridge pose (setu Bandha Sarvangasana on low blankets (one for torso and one for legs, with or without a belt tied around the legs).

Ultimately, to keep your spine healthy, it needs to move daily through a full range of motion. Our daily lives limit our motion dramatically, so this is where your yoga practice plays a powerful role in spinal health. With attention to your breath, intention of non aggression in your practice, and a healthy dose of common sense we can encourage our spines to move safely in our practice. Then the key is to take these skills back into our daily lives to encourage more healthy motion.