Meditating by Melina Meza

“There is emerging evidence from the extant literature to support the beliefs that modern adaptations of yoga practice are beneficial for mental and physical health. Here, we delineate very specific components of yoga practice (ethics, postures, breath regulation, and meditation) that are rooted in a historical framework and employed in varying degrees in contemporary contexts as a model for understanding how yoga may achieve its benefits – facilitating self-regulation and resulting in psychological and physical well-being.” —Gard, et alIf you’ve been reading this blog for any amount of time, you’ve probably realized that I firmly believe that yoga is an effective practice for psychological well-being as well as for physical health. Over the years, I’ve written about how yoga poses, breath work, and yoga philosophy all can help with psychological well-being (I’ve left discussions of meditation to some of our other readers because frankly that really isn’t my strong point). Although I don’t require scientific proof that these practices provide significant benefit for psychological health—sometimes your own experience is the best guide there is—I was excited to see an intriguing new study Potential self-regulatory mechanisms of yoga for psychological health by Gard, et al in the journal Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, which provided a model for understanding how yoga can achieve these benefits.

And since I have a handy medical researcher who I can ask for an assessment of studies like these (some are pretty dubious), I sent the study to Brad for a sniff test. It passed! In fact, his exact words were, “This looks pretty serious.” So I’m sharing the study with you today. Basically, the study proposed that yoga achieved its benefits by “facilitating self-regulation.” According to an article in Psychology Today Anger in the Age of Entitlement:

“Research consistently shows that self-regulation skill is necessary for reliable emotional well being. Behaviorally, self-regulation is the ability to act in your long-term best interest, consistent with your deepest values. (Violation of one's deepest values causes guilt, shame, and anxiety, which undermine well being.) Emotionally, self-regulation is the ability to calm yourself down when you're upset and cheer yourself up when you're down.”

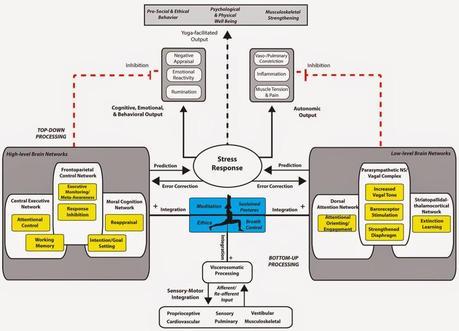

Well, I quite like the sound of that! In fact, it seems that both those aspects of self-regulation—the ability to act in your long-term interest, consistent with your deepest values, and the ability to calm yourself down and cheer yourself up—are what I've been writing about all these years, without even knowing about self-regulation. The proposed model for understanding how yoga provides the ability to "self regulate" is actually quite complex, however. The authors put it this way, “Specifically, we describe how yoga may function through top-down and bottom-up mechanisms for the regulation of cognition, emotions, behaviors, and peripheral physiology, as well as for improving efficiency and integration of the processes that subserve self-regulation.” Okay, that’s a lot of jargon! And the following figure may or may not give you an idea of what they mean by that. (Of course, if you’d like to read the entire paper, you can simple read it here).

"Ethics (Yama and Niyama): On the foundation of the yogic path of self-regulation lie ethical and moral precepts, which are specific examples of the standards or guidelines that contribute to self-control suggested by Zell and Baumeister (2013). "Postures (Asana): Modern and historic yoga practice manuals such as Light on Yoga (Iyengar, 1995) often suggest a connection between emotional states, physical health, and postures. Although this link has not scientifically been established yet for any particular poses (or set of poses) specifically, there is evidence linking posture, emotion, and mental health (Michalak et al., 2009, 2011, 2014). We attempt to address these hypothesized benefits in the following section.

"Breath Regulation (Pranayama): Traditionally, two benefits of pranayama are described to help the practitioner down-regulate arousal and increase awareness of the interaction between the body and the mind (Sovik, 1999)."Meditation (Pratyahara, Dharana, Dhyana, Samadhi): In the yoga tradition, the concentrative meditation techniques described in Raja yoga help the practitioner begin to see the conditions that lead to mental and emotional suffering (fluctuations) and the conditions that remedy suffering (i.e., mental stillness). Suffering is further described as a time when the mind is in an afflicted state—either grasping onto an experience, not wanting to let it go, or experiencing aversion, trying to push some object of experience away with force. In both cases, how one relates to one’s inner experience will create either more or less suffering. Such suffering can also be described as a mental state that prevents the mind from seeing reality without emotional bias. The ability to see reality clearly without bias, through meditation practices, is a revered tool of self-regulation within yoga (Cope, 2006) and similarly in mindfulness traditions (Vago and Silbersweig, 2012)."

Subscribe to YOGA FOR HEALTHY AGING by Email ° Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook