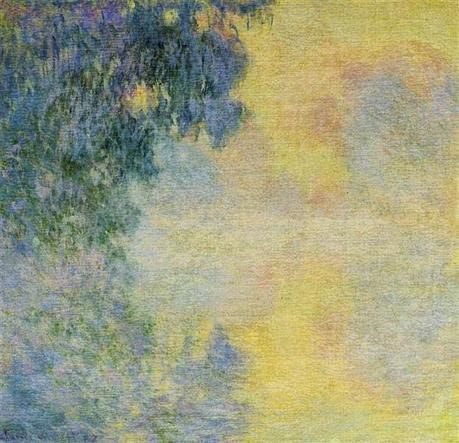

Misty Morning on the Seine, Sunrise by Claude Monet

In earlier posts I discussed the first five of the eight-fold path or eight rungs/limbs/steps of Yoga as described in the Raja Yoga section of the Yoga Sutras by Patanjali. Each step or limb prepares us for the next higher step. Thus, the first three limbs (yama, niyama, and asana help to prepare the body and enable practitioners to become more flexible, stable, and grounded. The fourth limb, pranayama, consists of breath practice and is designed to allow you to gain mastery over the respiratory process while building a connection between the breath, the mind, and the intellect. The fifth limb, pratyahara, helps us to discriminate between the harmonious and disharmonious impressions that we draw in through the five senses.Pratyahara serves as a fulcrum regulating external practices like asana and pranayama to internal observances like dharana (focus), dhyana (meditation) and samadhi (deep absorption). The three internal observances that also constitute the last three limbs in the Yoga philosophy have been described as “trayam ekatra samyama” and translates as “the three processes of dharana, dhyana, and samadhi, when taken together on the same object, place or point is called samyama”. While the first five limbs help us develop our power of focus and concentration, we continue to get distracted by our actions and our attention travels as well. Our focus constantly shifts as we try to become more adept at a particular posture or breathing technique. With a balanced breath, it becomes easy for the mind to focus on a single object or thought process while avoiding other mental dramas.

Dharana

Think about dharana or focus as the preparatory step towards attaining a deeper meditative stance. Dharana helps to reduce the chattering of the mind and filters out all irrelevant thought processes. To attain mastery over dharana, start out by focusing on any sound or a mantra (the silent repetition of a sound), or practice with an image or an object in mind. The most important thing to remember is that the goal is in the practice. If your mind wanders, just gently bring it back to focus without any judgment. Bringing the mind back to the object or the mantra—as many times as it takes—is what dharana is all about. The practice of dharana is not concentrating on the object rather it is the awareness with which you redirect the mind, again and again. This very practice—the mind running or getting distracted, you bringing it back—in essence is dharana.

Dharana does not have to happen only when we sit down to meditate. You can practice dharana when you are on your mat as well. Notice how your senses are acting during a pose: are you inundated with lot of thoughts, action, and dramas about the specific pose or are you intimidated by your neighbor’s perfect pose? Notice if your mind is very busy, constantly judging yourself or your neighbors. Can you gently practice pratyahara, let go of your sensory impressions, and start focusing on the pose itself? To “be in the pose” requires practice of dharana, letting go of the ego and focusing just on the pose so as to find your true self. Dharana gets easier as you practice it. When you get familiar with dharana, the mind becomes a much less restless place to be. Notice the joy, the pleasure, and bliss when you are able to successfully focus on something.

Dhyana

Since Dhyana (meditation) is a progression of dharana, the same techniques of dharana can lead you to dhyana. An extended period of focus prepares the path for dhyana. When the mind stops wandering and maintains a continuous period of stillness, at that point you are in dhyana. Dhyana or meditation is a state of being in which you are keenly aware without a need for focus and with the mind at its quietest. In that state of mind you no longer possess bodily awareness, the sense organs are not distracted, and the stillness produces few or no thoughts at all. In this state there is nothing else you can think about.

We can experience this state on the yoga mat as well. As you come back to a pose again and again, you are now able to do it smoothly and hold the pose without any distress or chattering mind, and you then become so overwhelmed by the pose that it becomes everything that you can think about. You are not distracted and you don’t want anything else as you feel transformed in that pose—you have achieved a complete state of satisfaction—this is dhyana. It comes when a process turns into something totally natural and there is nothing else you want to think about. It is not easy to reach the state of dhyana; one has to work towards it by means of dharana. It is for this reason that in the Yoga Sutras, dharana, dhyana, and samadhi are described as a three-staged process called samyama.

Samadhi

As you start to focus on an object or a mantra or some task, and as you naturally gravitate towards it and become one with it, you experience samadhi, “the insight.” Patanjali describes this eighth and final stage or limb as insight, rapture, or a state of ecstasy—a state in which the individual merges with his or her point of focus and transcends the self altogether.

Having a continuous practice of meditation helps the individual to achieve the state of samadhi. As you sit to meditate, both mind and body relax into a state of deep and profound restfulness. Any dramas in the mind or emotional upheavals get dissolved without effort, and a personal experience of complete peace, joy, and creativity unfolds. Anyone can learn this, and it does not require concentration or mental effort. The benefits are immediate, tangible, and cumulative, and the practice itself is relaxing and enjoyable. Seasoned meditators can naturally and effortlessly go into this state of insight. In this meditative state there is no separation between self and the world around; the individual experiences complete oneness and in that state there is only peace. One can get a similar experience on the mat as well.

After an hour of asana practice on the mat, your experience of samadhi is heavily dependent on the status of your mind. You experience oneness and complete peace when you are totally unaware of “I” or “mine” with the body, mind and intellect working in complete unison. This experience may be momentary, maybe even a fleeting second, but it is an experience of truth, uncontrollable joy, and peace.

Thus, the ultimate objective of yoga is reigning in the fluctuations of the mind to achieve complete liberation from mental turbulence—seeing things as they truly are and experiencing only peace. This would be the state of samyama, the ultimate step—peace or enlightenment—which can only be experienced individually. As BKS Iyengar aptly put it, “You must do the asana with your soul.” This would mean being in samyama, which requires cultivating the quality of focus, concentration, and letting go of the ego, including your body image, to feel open, grounded, and calm and experience oneness with your true self. In this state, you experience contentment and enjoy a sense of accomplishment. It’s a great positive spiral and it results in improved health and happiness.

Subscribe to Yoga for Healthy Aging by Email ° Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook ° Join this site with Google Friend Connect