Fuji, Mountains in Clear Weather by Hokusai

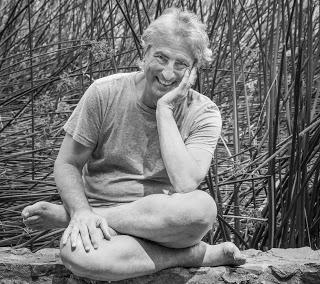

As Nina was working on correcting my earlier misapprehension about the yogic concept of avidya (see Spiritual Ignorance ), at her encouragement I reread my post from 2015 What if We Could Weed Out Avidya? where I had taken a stab at defining avidya based on multiples sources that I had studied over the years. As you will read below, in that post I was describing everyday forms of ignorance, which are obviously important and do also cause some suffering, but were not actually what the yogis were trying to get at. So I thought I’d go to my local source for everything related to yoga history and philosophy, Richard Rosen, author of many books on yoga—including my new favorite, Yoga FAQ, where he actually addresses this beautifully—to get his feedback on that post of mine. What he wrote to me was so important, interesting, and well written that I'm including what he wrote in this post in its entirety. After his discussion, you can see my response to him (and to you)—BaxterRichard: You’ve written an excellent/insightful piece on what we could call “everyday ignorance,” but this isn’t quite the same thing as avidya in a traditional or better classical sense. Avidya, I’m sure you know, means “not knowing" (a "not" + vidya "to know"), and you correctly attribute it to a misapprehension at the core of our lives. But the misapprehension is more specific than “having a mistaken understanding of the way things are.” It’s actually a “mistaken understanding” of your true Self (with a capital S). We mistakenly believe we’re the person summed up on our driver’s license, the one in the bad picture nowadays with purple hair and the low-balled weight.

That “person” is nothing more than a product of fluctuations, which chain into habits (samskaras), and then into personality traits (vasanas). According to classical yoga human consciousness is, and this is a bit hard to grok, a material process called citta (pronounced CHIT-uh); in other words, if I look across my room right now at my guitar, my citta assumes the shape of that instrument. Our perception is possible then because my citta is composed of the same stuff as the material world.Anything material is diametrically opposed to the Self, purusha, which is completely immaterial. Trapped by our misapprehension we’re convinced that we’re an individual limited in time, space, and knowledge (asmita "ego-ness), that we need to have certain things to make us complete (raga "desire") and should avoid other things that we don’t like (dvesha), and that we need to cling to this unknowingly mistaken identity come heck or high water (abhinivesha). These are the kleshas, avidya and its four accomplices. Our suffering from avidya then, while anxiety may be a symptom, goes to the core of our being. It’s called duhkah, literally “bad space" (pronounced dew-kuh) that is a kind of existential suffering that permeates our lives. On some level, we’re all aware of that suffering, though most people chalk it up to mundane things like lack of money, unhappy relationships, or unfulfilling jobs. This isn’t to say that the suffering we experience in our lives is superficial and “wrong-headed,” it’s certainly real enough. But no matter how much money we earn, how supportive our relationships, or how fulfilling our work, that suffering will always persist. This is the main question that every yoga school wants to answer, "Who am I?" As Baxter correctly says, the fluctuating mind “muddies the waters” and prevents us from seeing the truth about ourselves. The solution as he says, at least according to classical yoga, is to “gain control of the fluctuations” through a very intense form of meditation. Quieting the fluctuations is sometimes compared to slowly cleaning a dirty mirror that we’ve been staring into all our lives. At the practice's culmination, when the "mirror" is wiped clean, our true "face" is revealed and avidya and the suffering it brings are overcome. Hooray! By the by the classical yamas and niyamas aren’t prescribed as means to make us better citizens. This may be a byproduct, but their real purpose is to calm things down in our wildly fluctuating citta and prepare us to meditate. There are way better yamas and niyamas in other texts for making us into nice guys, like compassion, hospitality, generosity, and open-mindedness. I’d also point out that the Iyengar and Desikachar books aren’t strictly “translations." They’re interpretations of the text that tone down the (for us) objectionable demands made by the yamas/niyamas that were originally directed toward world-renouncing ascetics. Hopefully, my clarifications will help your readers have a clearer distinction between the core avidya and its everyday expressions. Baxter: Well, I certainly think what you have shared with me and our readers today will do just that! And I also appreciate the distinction you make about the yamas and niyamas, as not actually being equivalent to the 10 commandments, but tools to advance one’s progress in quieting the mind. Thank you so much for taking the time to provide feedback on my post and the very important concept of avidya. I suspect we may check in with you, again, about this and other topics. And my sincere apologies to our readers for any confusion I may have caused through my incomplete and inaccurate description of avidya in the past. Richard Rosen teaches public classes locally at You and the Mat in Oakland, CA. His latest book from Shambhala is Yoga FAQ (2017). He can be reached through his website at RichardRosenYoga.com.Subscribe to Yoga for Healthy Aging by Email ° Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook and Twitter ° To order Yoga for Healthy Aging: A Guide to Lifelong Well-Being, go to Amazon, Shambhala, Indie Boundor your local bookstore.