After reading Women's Flexibility is a Liability in Yoga by William Broad and responding with Is Women's Flexibility a Liability in Yoga? Shari's Response to William Broad and Differences Between Male and Female Pelvic Structures I thought some general advice about how to keep your hips healthy and happy would be helpful for both women and men alike.

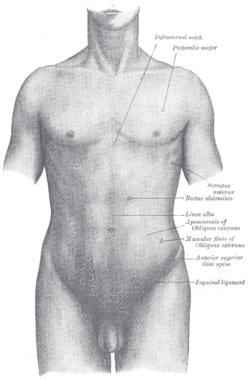

I suggest you start by finding your hips and assessing your mobility. I often ask my students to begin by locating their hip joints. They are not on the outside of your pelvis but the spot where when you lift your legs up when you are climbing chairs, you feel the muscle moving under your fingers. This is the head of your femur (thigh bone).

Hip Joint is located approx. behind Inguinal Ligament

Next, test your own amount of leg external and internal rotation. Lie on the floor in Savasana (Corpse pose), with your feet slightly apart. Then, moving from your hips while keeping your legs straight, turn your legs out so your feet turn away from each other. This is external rotation. As you do this motion, make sure you are doing the movement from your hips not from your lower leg/knee. Observe how far you can turn your legs out, and whether both sides are the same. Next, moving from your hips while keeping your legs straight, turn your legs in so your feet are turning toward each other. This is internal rotation. Again, as you do exercise, make sure you are doing the movement from your hips not from your lower leg/knee. Observe how far you can turn your legs in, and whether both sides are the same.Once you can sense how much actual hip rotation you actually have (and whether you are the same on both sides), you can begin to assess your own foot placements for standing poses. Start by exploring your particular hip alignment in wide-legged, side-facing standing poses, such as Warrior 2 or Triangle pose. Try whether it is easier to feel your hip position if you step into your standing pose from Mountain pose (Tadasana) by stepping back with your left leg and keeping your right leg stable, rather than stepping the right leg forward and the left leg back (the traditional Iyengar yoga cue). Then, as you take your stance in the pose, first try keeping your front heel in line with your back middle arch and notice how your back leg internal rotation feels. If you find that in order to do this alignment you have to reposition your lower leg moving from your knee to correct this alignment, try a wider front heel to back heel stance and see if this feels like less tension in your knees and back hip.

I remind my students to not square the pelvis (see Squarer's Beware) but to allow the front pelvis to be in the same plane as the front knee and the back knee to be in the same plane as the back pelvis. In these types of poses, your front leg will be in external rotation relative to your back leg, which is in internal rotation. While working with your hips, don’t forget your knee positioning—to protect your knees, please align your knee with the middle of your ankle joint and generally in line with your second toe. All these joints should be lined up. Proper alignment that is optimum for you may take some experimentation, so if in you’re doubt, use a mirror to help you check exactly which direction your knees and hips are facing.

Continue this exploration in all your wide-legged standing poses, such as Extended Side Angle pose and Warrior 1. Try not to force rotation by causing your pelvis to move more than is comfortable over your stable legs. And don’t be afraid to line up your front heel with your back heel if that gives you more a sense of freedom in your hip joints! Turning one joint surface too much in relationship to another (the femur turning in the cup of the acetabula) will put stress and strain on the hip joint capsule and the ligaments that keep the hip within the socket of the acetabula.

Some rules of thumb for standing poses:

- Any pain in the groin or knees need to be respected. Please back out of the position.

- Pay attention to pain in any body part, especially when doing single leg positions (balancing poses) and try to modify to avoid reproducing the pain. It is really important to learn how to use your muscles (which need to contract on both sides of the joints ) and bones to support your weight rather than depending on the ligamentous structures inside the joints to provide stability. Pain can come from compressing the pain sensitive structures inside joints (ligaments, tendons and capsules) or from moving beyond the joints limits of mobility (see Range of Motion: Yoga's Got it Covered).

- Try to avoid overly stretching the front of your thighs close to your hip crease in your back leg in poses like Warrior 1, Triangle pose, etc. And for lunges, avoid going into your end range with your back leg and “hanging out” there.

Sitting on a Prop

Remember the spine has curves for a reason—they serve as a means to distribute weight through the spine along the vertebral bodies. If you sit in a reversed or slumped position, you change the weight-bearing forces onto the facet joints and the soft tissue structures of the back (muscles and ligaments and discs). When you sit with your bones providing the support, you will tire less and breath better!Finally, in bent leg positions, you may need to support your outer legs to prevent the sensation of hip pain. You can place folded blankets or blocks under your knees to keep your legs from hanging in space.

Sitting in Hero pose (Virasana) is a different hip position—internal rotation. Depending on the degree of internal rotation that you have, it may or may not be possible for you to sit with your knees together. In this case, try sitting on a higher support so your pelvis can be over the heads of your femurs (thigh bones) not behind them, and allow your knees to separate but not roll out. Align your thighs with your hip joints. Try palpating your hips in Hero pose and experiment to see if changing how close together your knees are helps to make the pose more comfortable. Reclined Hero pose (Supta Virasana) is also a different hip position because internal rotation is now superimposed with a backbend and if your hips can’t move into internal rotation, then your lumbar spine and sacrum will try to compensate for the lack of movement which can also cause pain and discomfort. This is especially the case for women because our sacroiliac joints may not lock down in weight bearing in this backbend so there can be an uneven distribution of weight in the back bend position. Learning how to prop for both Hero pose and Reclined Hero pose is really important, and you may need a teacher to help you with these alignment issues.

The bony structure and joint orientation of your hips in the acetabulum of the pelvis are variables that cannot be changed. Bones can only move in certain ways due to form and function. We may try to compensate for our immobility by excessively overusing our soft tissue ligaments and joint capsules to try to gain flexibility that we lack. Or, we may inadvertently try to make our hips move beyond their anatomical possibilities by the sports that we do or the yoga that we practice because we think the goal is more flexibility. This certainly can cause excessive wear and tear of the hip joint leading to cartilage deterioration and arthritis. So the issue really is our perception of what a pose is supposed to look like. How a pose feels is very individualistic, and it is not good to struggle with a pose that always causes pain. Sometimes for some of us certain poses aren’t attainable in the classical sense, but I believe that if we can recreate the feel of the pose we can get the benefits. For example, Dancer’s pose (Natarajasana) is a challenging balancing backbend in which you raise one bent leg behind you and reach overhead with one bent arm to hold the toes of your raised foot. However, modifying this pose by reaching your straight arm back to hold your foot instead of up overhead will allow you to recreate the beauty and concentration of the classical pose.

For healthy aging, I believe that struggle may not always be the best way to go; instead, learning to be less aggressive and more adaptive is a best way to approach asana. Mental focus and alertness with concentration on using the breath to create asana is more satisfying than trying to force oneself into contortions that may not be possible for one’s innate physical structure. This is how we balance and protect ourselves from injury during the physical asana practice.