Q: I was wondering if there are any resources or practices that you can share with me for people who have mitral valve regurgitation. I myself have it, maybe born with it but some of my students mentioned that as well. I haven't found any info on yoga and people who have that and low blood pressure and it is not due to a heart attack. Are inversions ok? Running? The pace of walking and running?

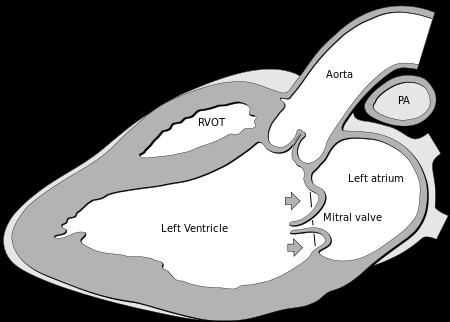

Q: I was wondering if there are any resources or practices that you can share with me for people who have mitral valve regurgitation. I myself have it, maybe born with it but some of my students mentioned that as well. I haven't found any info on yoga and people who have that and low blood pressure and it is not due to a heart attack. Are inversions ok? Running? The pace of walking and running? When I was in my full-time family medical practice, I had quite a number of patients who had a diagnosis of Mitral Valve Prolapse (MVP), which at times resulted in “regurgitation” of blood from heart’s left ventricle backwards into the left atrium, the opposite direction that the blood is supposed to flow. The left side of the heart receives blood freshly oxygenated from the lungs, and pumps it out to the rest of the body. The one-way valve (usually!) between the entrance chamber, the atrium, and the large exit chamber, the ventricle, is the mitral valve. Normally, the mitral valve allows the blood from the atrium to flow into the ventricle when the upper chamber muscle walls contract, and it closes and prevents backflow when the ventricle chamber walls contract and send the blood out the aorta and to the rest of the body. If the valve leaflets just bulge back (prolapse) toward the atrium, there might be no leakage of blood. Sometimes, however, they both bulge backwards and separate a bit, allowing the regurgitation our reader experiences. For most people, MVP is not life threatening and does not require any special treatment. For a small minority however, the condition does require treatment.Approximately 2% of the US population has MVP. Many people do not even know they have it. Although you may have had this condition your entire life, you may never have specific symptoms related to the prolapsing valve, and if it is discovered by chance while some other condition is being investigated, you may be quite surprised to discover you have it. Often, those who have symptoms also have the regurgitation. Symptoms are usually mild and develop gradually, and can vary quite a bit from person to person. The most common symptoms are:

- Racing or irregular heartbeat (arrhythmia)

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

- Difficulty breathing or shortness of breath, often when lying flat or during physical activity (this could require modifications for our yoga practice)

- Fatigue

- Chest pain that's not caused by a heart attack or coronary artery disease

In addition to the echocardiogram (ultrasound test), your doc might order a treadmill stress test to see if there are any limitations on your ability to exercise. So, for our reader, you might request this test if you are worried about the safety of a strong yoga practice as to relates to your MVP. And, as with many conditions that might affect your yoga practice or other forms of physical activity and exertion, you will need to do some investigating and experimenting to see what works for us and what does not. If you have MVP AND low blood pressure (see Friday Q&A: Low Blood Pressure), you may want to be more cautious and watchful when entering, maintaining, and exiting inversions. It might actually be getting up after an inversion where you would need to be most cautious, so take it slow and see how your body responds. Start with easy inversions, such as Standing Forward Bend (Uttanasana) Downward-Facing Dog pose (Adho Muka Svanasana) or Legs Up the Wall pose (Vipariti Karani) and see how these go. Then advance to more challenging inversions (it is always a good idea to learn these from an experienced teacher). For the majority of people with MVP who take up yoga, the condition will likely be a non-issue, but it is still worth checking with your doctor. For that smaller minority of individuals who are experiencing dizziness, shortness of breath, or heart arrhythmia, I’d recommend discussing limitations with your cardiologist before diving into a more vigorous and rigorous yoga practice. However, gentle and restorative yoga would likely be safe for just about anyone with MVP, as long as you are able rest supine without shortness of breath. —BaxterSubscribe to Yoga for Healthy Aging by Email ° Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook ° Join this site with Google Friend Connect