by Nina

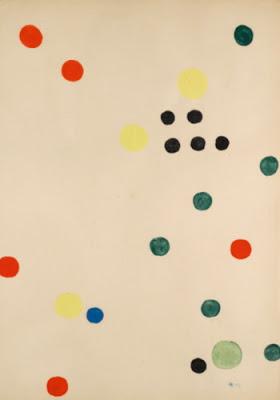

Signal Series by Yuri Zlotnikov

Although we tend to consider anger a “negative” emotion, it’s actually a healthy signal that alerts us to a potential threat. My friend Dr. Scott Lauze, who is both a psychiatrist and practitioner of mindfulness meditation, says, “The way I think about it, anger is a normal response to certain situations, even a healthy one, and expressing that in a skillful way is normal and important.”Anger can signal there is a potential threat that is physical, emotional, or both. And the threat could be to the well-being or survival of yourself, of others, or even of an organization, a community, or country that you care about.Generally, expressing anger in a skillful way means bearing the yamas in mind as you respond, particularly the yama ahimsa (non-violence), which is the number one yama in every yoga text, as well as satya (truthfulness). But the skillful way to respond to your anger also depends on the particular situation. Sometimes the threat is real and reacting to it by working to find a possible solution to the problem can be the best response. In Real Change, Sharon Salzburg says:“When an interaction, person, or experience makes us angry, our bodies and minds are effectively having an emotional “immune” response. We are telling ourselves to self-protect, the same way blood rushes to the site of an insect bite. It is often anger that turns our heart-thudding distress into action, that pushes us to actively protect someone’s right to be happy, to be healthy, to be whole.” —Real Change, page 59So, anger at a real injustice or threat is not only a healthy response but it can lead to beneficial acts and even to social activism.But other times, anger can be triggered automatically due to deep patterns of behavior created by previous experiences you’ve had. Charissa Loftis says that she experienced anger on a regular basis when interacting with her family because of these types of patterns:“I grew up in a home marked by PTSD, alcohol abuse, and depression. These issues heavily influenced our interactions with one another, and over the decades, those interactions shaped our habits and familial roles within the family.”In situations like these, the automatic anger you respond with, while natural, might be clouding the issues for you, preventing you from finding a new way of navigating the situation. In that case, a skillful response might mean taking a different tack. If the situation is one you want to improve, you might cultivate compassion for all those involved in the conflict. This is what Charissa did. She started by practicing compassion for herself, which led her to be able to cultivate compassion for her parents, especially for her father who was a Vietnam War veteran. This, in turn, created an opening for her to see her family situation from a new perspective and to changing her actions accordingly, leading to a positive outcome for the entire family (see Dissolving Family Related Anger for her story).But when a situation is dangerous for you and there is no workable or healthy solution, the skillful response could be to walk away.Another potential pitfall with anger is holding on to it for too long, leading you to cycle again and again through the same negative feelings and painful memories. This form of anger is called resentment. Resentment not only doesn’t resolve the conflicts you are reliving, but it can also cause you to experience, as Sharon Salzburg puts it (Page 59), “emotional bondage.” Dr. Lauze describes resentment this way:“We keep that little burning ember of anger alive and fan the flames from time to time. But, like a mentor told me, resentment is like lighting yourself on fire, hoping the other person dies of smoke inhalation. It ends up hurting us more than it hurts the other person, who frequently has forgotten all about the precipitating event and has moved on and has no idea you are harboring the resentment.”For resentment, there are many different techniques that you can use to “let go” of your anger so you can move on. See Letting Go, Part 1 for some ideas.What if, in the midst of anger, you can’t tell what the most skillful response would be? In the moment, see if you can take a deep breath and stop for a “precious pause,” as Patricia Walden calls it. This may give you a brief window in which to assess your current situation before simply reacting. If you have more than a moment, focus on your exhalation. After each inhalation, exhale consciously and deliberately, maybe even making a "positive" sound as you do so. These conscious exhalations may calm you down a bit and, as Iyengar yoga teacher Jarvis Chen explains, because anger makes your diaphragm tight, conscious exhalations can also help release that constriction.

If you have more time, you can use your yoga practice to cool down from the heat of anger. Yoga stress management practices, such as supported inverted poses, restorative yoga, and guided relaxation, can dial down your fight, flight, or freeze response, which in turn can help you think more clearly. See Stress Management for When You're Stressed for several ideas. However, if you're feeling too worked up for quieter practices, Jarvis suggests starting with active yoga poses, especially those that get you out of your brain and into your body, such as Downward-Facing Dog pose, Standing Forward Bend, and even Handstand, if you do it. Then you can move on to one or more of your favorite stress management practices. When you're ready, you can also practice one or more sessions of self-enquiry (tarka) to delve more deeply into the reasons for your anger. I’ll write about self-enquiry in the future, but for now I’ll end with a quote from Dr. Lynn Somerstein, who is both a yoga therapist and a psychoanalyst, and who describes herself as an “anger expert” because she grew up with people who were angry all the time and whose retaliatory rage caused her to hide her angry feelings.“Yoga brings you closer to your body, feelings, and mind. Thich Nhat Hanh said it best, “Breathing in, I know I am angry. Breathing out, I know that the anger is in me.” The first step is to recognize and befriend your feelings, and then ask yourself why and how you are angry. Know that you are human, and the person you’re angry with is human, too.” —Dr. Lynn Somerstein

Subscribe to Yoga for Healthy Aging by Email ° Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook ° To order Yoga for Healthy Aging: A Guide to Lifelong Well-Being, go to Amazon, Shambhala, Indie Bound or your local bookstore.