When Monica, a 50 years-old mother of two, visited her doctor for a routine check-up she was told her blood pressure was 142/83 mmHg. That made her hypertensive, at least in the eyes of the health care system.

Her doctor prescribed a blood pressure drug and asked her to see him again in 2 month’s time.

Upon her follow-up visit Monica’s blood pressure had come down to 132/82 mmHg. The doctor recommended to continue taking the drug as it obviously kept her blood pressure in a healthier range.

What neither Monica nor her doctor realised was that she (a) quite possibly wasn’t hypertensive at her first visit, and that (b) the drop in blood pressure was unlikely to reflect the true effect of the drug, if there was an effect at all.

How reliable are hypertension diagnoses based on office blood pressure measurements?

Blood pressure is highly variable as it changes from one heartbeat to the next. This high variability has raised the question how reliable the typical one-visit snapshots at your doctor’s office really are.

Researchers of the Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation of Yale New Haven Hospital and Yale University set out to answer this question [1]. They looked at the visit-to-visit variability of 7.7 million blood pressure readings taken from more than 537,000 adults.

That makes it the largest ever study of blood pressure measurements performed at consecutive visits within a 90-day window.

The results show an average variability – expressed as a standard deviation (SD) – of 10.57 mmHg.

What does that mean for you?

Let us assume your true systolic blood pressure is 125 mmHg.

By the way, you can never know your true blood pressure, because of inevitable inaccuracies of measurements and the aforementioned beat-to-beat variability. That’s why researchers work with averages and standard deviations.

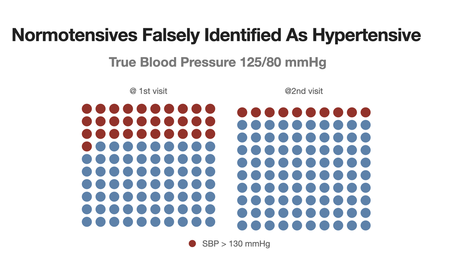

So, let’s say you and 99 other people with “true” systolic pressure of 125 mmHg have your blood pressure measured at your doctor’s office.

Approximately 31 (one third) of you will have a reading in excess of 130 mmHg, which is currently the defining threshold for hypertension (in the US; in Europe we see it a little more relaxed, with 140 mmHg being considered the “red line).

That is, you have a one-in-three chance of being suspected of having hypertension or pre-hypertension even if your blood pressure is normal.

Now let’s further assume that these 31 people - whose blood pressure is perfectly fine -– will be invited by their doctor for a follow-up visit within 3 months’ time. How many do you think will still have a reading above the “red line”?

Again, one third of this purportedly hypertensive cohort. That is, ten people will have a second reading that puts them into the hypertensive, respectively pre-hypertensive range (depending on where you reside).

So, here is the potential for 31 unnecessary follow-up consultations, 10 unjustified diagnoses of a chronic condition, and all the medication and treatment costs that come with it. Not to mention the needless anxiety that many of the misdiagnosed people will suffer

How reliably can office blood pressure measurements identify a drug’s effect?

Instead of only looking at how reliably doctors can identify hypertension, the researchers also asked how reliably doctors can detect and quantify the effects of blood pressure medication.

Again, the results are an eye-opener.

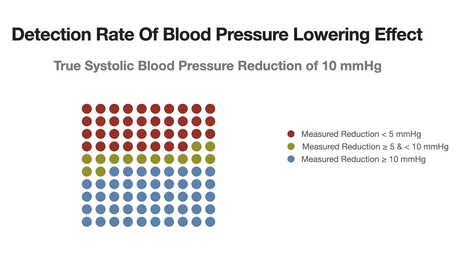

The researchers looked at how blood pressure readings changed over a visit-to-visit window of less than 90 days. That is the typical timeframe for a doctor to check how a new or modified prescription affects a patient’s blood pressure.

The mean visit-to-visit change in untreated individuals and individuals with no between-visit change of treatment was very close to zero (as would be expected). But the standard deviation (the measure of variability) was pretty high at 15 mmHg.

If you take these data and run a simulation (as I have done in preparation of this post) in which you assume that a blood pressure lowering intervention will result in a true 10 mmHg drop of systolic blood pressure between 2 visits, you’ll find that fully 38% of the treated individuals will show a blood pressure reduction of less than 5 mmHg, or even an increase.

Why is this important?

Because a 5 mmHg drop is the accepted threshold for a clinically relevant change in blood pressure. That is, a change that meaningfully reduces the risk of major cardiovascular events.

As an aside: the 38% of my simulation is even more optimistic than the 42% which the researchers pulled out from their real-life data. I am always skeptical about published numbers, that’s why I love to run simulations to check whether the data make sense.

Again, what does that mean for you?

For 4 out of 10 patients who have been prescribed an antihypertensive drug, the follow-up measurement of the drug’s effect will underestimate its true effect.

Keep in mind that the “4 out of 10” is probably an optimistic figure because the simulated drop of 10 mmHg exceeds what is typically achievable with any single drug [2].

The doctor’s knee-jerk reaction will probably be to either increase the dose or add another drug to the treatment combo.

The Alternative To Office Blood Pressure Measurements

What should be the reaction in both of the scenarios that I described above?

Not to rely on office blood pressure measurements.

I am not kidding. And I am not the only one saying this.

The hypertension societies around the world are warming up to the idea that regular and frequent home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) is more informative than the occasional BP recording at the doctor’s office. That’s what the 2023 guidelines of the European Society of Hypertension tell us [3].

The holy grail of HBPM is continuous cuffless blood pressure measurement through wearables. We are not there yet, but we are getting close. And I will address the pros and cons of this technology in one of my next posts.

What You Can Do Today

One convenient way of doing HBPM is by using a self-inflating WIFI-capable device that has also been validated.

In my team we are working with the Withings BPM Connect device, which directly communicates with our DIY lifestyle medicine platform.

My team and I have developed this platform to democratize access to individualized lifestyle medicine, making it accessible to lay-users and their doctors.

For the hypothetical Monica HBPM and our platform would certainly have been helpful. First, in finding out whether she is hypertensive, second, in testing how a change in her dietary or exercise habits might affect her blood pressure. All that before starting on any medication.

PS:

This post contains referral links for the Withings device on Amazon (Germany) and Amazon (UK). If you purchase the device from there, I will receive a small commission at no additional charge to you.

PPS:

You may follow me on LinkedIn for regular updates

Hashtags

#ScienceKitForHealth

#Blood Pressure

#Hypertension

#HomeBloodPressureMonitoring

#Withings

References

[1] Lu Y, Linderman GC, Mahajan S, Liu Y, Huang C, Khera R, et al. Quantifying Blood Pressure Visit-to-Visit Variability in the Real-World Setting: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2023:305–15. doi:10.1161/circoutcomes.122.009258.

[2] Wald DS, Law M, Morris JK, Bestwick JP, Wald NJ. Combination therapy versus monotherapy in reducing blood pressure: meta-analysis on 11,000 participants from 42 trials. Am J Med 2009;122:290–300. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.038.

[3] Mancia Chairperson G, Kreutz Co-Chair R, Brunström M, Burnier M, Grassi G, Januszewicz A, et al. 2023 ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension Endorsed by the European Renal Association (ERA) and the International Society of Hypertension (ISH). 2023. doi:10.1097/HJH.0000000000003480.