– contributed by Lizette Royer Barton.

I have to start by saying that every day I am in awe of young people, both in the history of psychology and their presence in the pressing issues of today. Change is slow, painfully slow at times, and thankfully we have young people who are willing to fight the long, painful fights from which we eventually all benefit.

In digging through the SPSSI records recently I unearthed some materials regarding the early history of the Black Students Psychological Association (BSPA), a group of young Black psychology students who took matters into their own hands and demanded change. In honor of Black History month and in honor of young people, specifically young people of color, let’s talk a little bit about BSPA and recognize the group’s importance in the history of psychology.

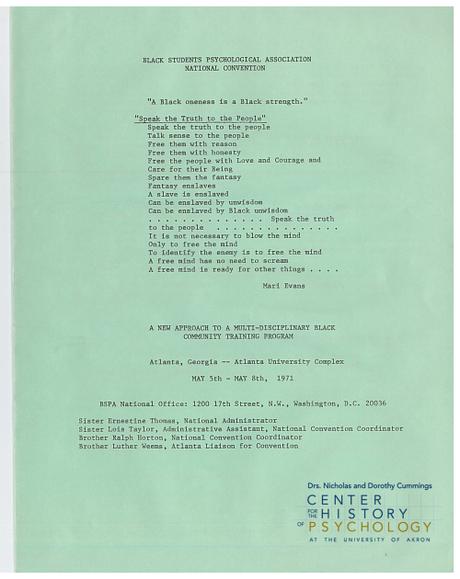

BSPA 1971 National Convention program, SPSSI records, box 743, folder 6

You may have heard the story the story about a group of Black psychology students disrupting George Miller‘s presidential address at the 1969 American Psychological Association’s annual convention in Washington DC. Students disrupting the “old guard” makes for a good story after all, but what happened after that? Heck, what happened before that?

Gary Simpkins was a undergraduate psychology student at California State College in Los Angeles (now known as California State University, Los Angeles) when he took a psychology course with Dr. Charles Thomas, a founding member of the Association of Black Psychology (ABPsi) who at the time was serving as co-chairman of the group. With Dr. Thomas serving as a faculty adviser Simpkins and his fellow students started the Black Students Psychological Association.

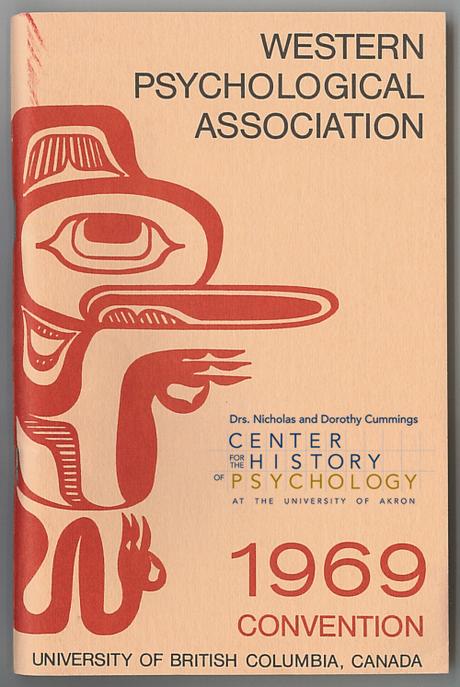

According to Simpkins & Simpkins (2009), early BSPA meetings took place at Thomas’ home and a community mental health center, and Thomas arranged for members of ABPsi to meet regularly with the students. With the support of ABPSi, BSPA decided to attend the Western Psychological Association (WPA) convention in Vancouver, British Columbia June 18-21, 1969.

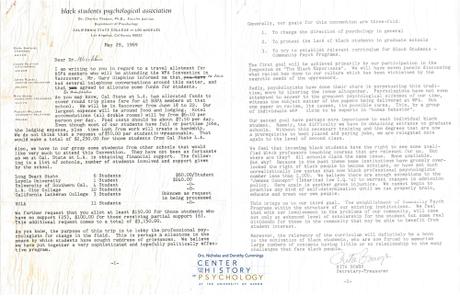

The image below is a May 1969 letter from BSPA secretary-treasurer Rita Boags to SPSSI executive secretary Caroline Weichlein seeking travel funds for BSPA members to attend WPA in Vancouver. Notice Boags hand written “Dr. Zimbardo” in the first paragraph. Following receipt of the letter, SPSSI secretary-treasurer Robert Hefner contacted Zimbardo to inform him that SPSSI did not have the funds for the request. The CCHP also has a copy of Philip Zimbardo’s June 9, 1969 response to Rita Boags in which he informs her that SPSSI is unable to grant the funds.

SPSSI records, box 743, folder 1

But funding aside, let’s take a closer look at Boags’ letter and BSPA’s goals for attending the WPA convention at the top of page 2.

Boags to Weichlein, page 2, SPSSI records, box 743, folder 1

Simpkins & Simpkins (2009) wrote that Thomas helped to get them onto the convention program and they scheduled a panel titled, “Racism in Organized Psychology.”

I took to the WPA records and located the 1969 program.

Western Psychological Association records, box 490, folder 1

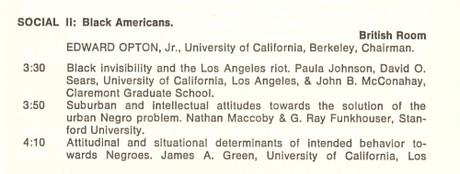

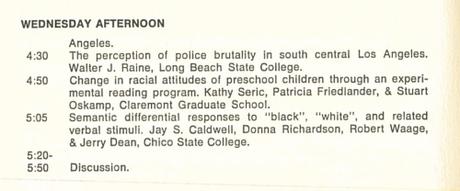

I scoured the program but did not find a panel titled, “Racism in Organized Psychology.” However I did find two sessions of interest – Social II: Black Americans and Challenge and Change in 1969: Black Perspective in Psychology.

1969 WPA convention program, WPA records, box 490, folder 1

Perhaps the panel Simpkins is referring to was ABPsi’s nearly three-hour symposium, “Challenge of Change in 1969: Black Perspective in Psychology.”

Did BSPA members present their papers during this time?

1969 WPA convention program, WPA records, box 490, folder 1

From the materials housed here at the CCHP I could not determine whether or not that was the case. Does anyone know?

BSPA seems to have been founded in either later 1968 or early 1969. The annual Western Psychological Association convention was June 18-21, 1969. The American Psychological Association convention in Washington DC – the meeting where Gary Simpkins and BSPA members interrupted APA president George Miller’s presidential address – was in September of 1969. Those students got to work quickly!

BSPA addressed the APA Council the following day (September 2, 1969) and outlined five specific concerns and their plans for implementation: (1) the recruitment of Black students into psychology; (2) the recruitment of Black faculty members into psychology; (3) the gathering and dissemination of information concerning the availability of various sources of financial aid for Black students; (4) the design and provision of programs offering meaningful community experience for Black students in the field of psychology; and (5) the research and development of terminal programs at all degree levels that would equip Black students with the tools necessary to function within the Black community.

You can go out on your own and find what happened next regarding APA (start here, Baker page 492). The gist is that APA President George Miller and President-Elect George Albee agreed to meet with members of BSPA and ABPsi to work out details. They met in Watts in Southern California for two days and in October a specific plan was reported back to APA Council.

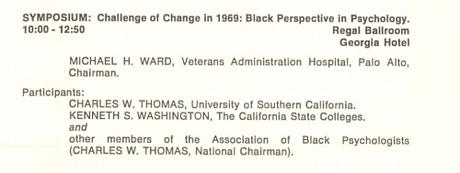

BSPA members Gary Simpkins and Phillip Raphael wrote a report detailing the events at the 1969 annual convention, the meeting with APA Council, and the subsequent meeting with Miller and Albee. It was published as a “special insert” in the American Psychologist (1970) – Black Students, APA, and the Challenge of Change.

SPSSI records, box 743, folder 6

One year later, the Black Students Psychological Association had a national office in Washington, DC and they held their first national conference in Atlanta, GA.

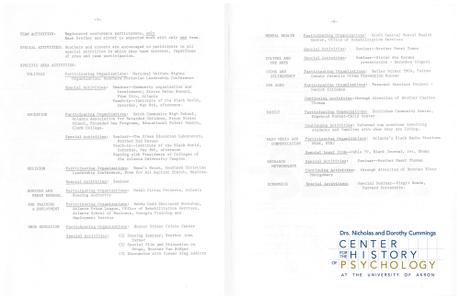

BSPA 1971 National Convention program, SPSSI records, box 743, folder 6

The program was innovative and really cool.

There were team activities, special activities, and specific area activities organized around the following themes: politics, education, religion, housing and urban renewal, job training and employment, drug education, mental health, culture and the arts, crime and delinquency, our aged [senior citizens], family, mass media and communication, research methodology, and economics. The specific area activities were held all around Atlanta with local leaders hosting and participating.

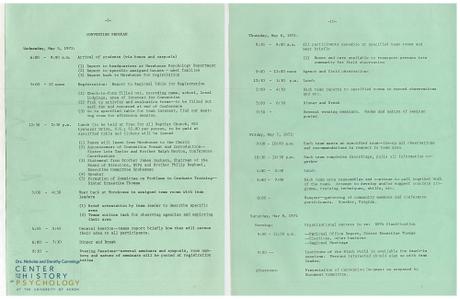

BSPA 1971 National Convention program, SPSSI records, box 743, folder 6

BSPA 1971 National Convention program, daily schedule, SPSSI records, box 743, folder 6

This wasn’t just academics reading papers with audience members asking “questions” (AKA not really asking questions but rather telling everyone in the room what they already know. You guys know what I’m talking about). This was an engaged group of people, mostly students, tackling real issues in the community with psychology.

Awe inspiring.

The SPSSI records also include a bit of information about the BSPA’s second national convention in 1972 on the Bronx Campus of New York University but that is where our archival trail runs cold.

According to Bertha Garret Holliday (2009), “In that same year [1971], an ideological-political chasm began to emerge between ABPSi and BSPA. Meetings focused on effecting a merger between the organizations met with little success.”

And in a very brief chapter by Simpkins in Robert L. Williams (2008) History of the Association of Black Psychologists: Profiles of Outstanding Black Psychologists, Simpkins asserts that BSPA “…continued to exist for a number of years as an affiliate of ABPSi. Later, BSPA made a transition to the now existing ABPSi Student Circle.”

I want to know more. I want to know about this group and its members and how the BSPA may have shaped their careers in psychology. I want to know what came out of that first meeting in Atlanta. I want to know more about the “ideological-political chasm” between ABPSi and BSPA. I want to know more about ALL OF IT!

But alas, I have reference requests in my inbox and my “real job” to attend to. My references are below. Someone take up this project and get back to me. And in the meantime, let’s hear it again for the young people who always have and always will be the change makers!

References

(Some of these sources are cited above but others are not. Many are available in full-text via PsycNet. All of them are good so go read them.):

(Jul 1969). Black Students Demand Changes in Psychology. SPSSI Newsletter, 3.

(Jul 1970). BSPA opens office in APA building. The Washington Report, 6(7), 1, 3.

Baker, D. B. (2003). The challenge of change: Formation of the Association of Black Psychologists. In D. K. Freedheim & I. B. Weiner (Eds.), Handbook of Psychology, Volume I: History of Psychology (pp. 492-495). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Blau, T. H. (1970). APA Commission on Accelerating Black Participation in Psychology. American Psychologist, 25(12), 1103–1104.

Holliday, B. G. (2009). The history and visions of African American Psychology: Multiple pathways to place, space, and authority. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 15(4), 317-337.

Jones, R. L. (Ed.). (1991). Black psychology. Cobb & Henry Publishers.

McKeachie, W. J. (1970). Report of the Recording Secretary. American Psychologist, 25(1), 9–12.

Nelson, B. (1969). Searching for social relevance at an APA meeting. Science, 165(3898), 1101-1104.

Sawyer, J. (1970). Why women, Black people, students, and other interest groups should be represented in the APA. American Psychologist, 26(6), 557-558.

Simpkins, G., & Raphael, P. (1970). Black students, APA, and the challenge of change. American Psychologist, 25(5), xxi–xxvi.

Simpkins, G. and Simpkins F. (2009). Between the Rhetoric and Reality. Lauriat Press.

Thomas, C. W. (1970). Psychologists, psychology, and the black community. In F. F. Korten, S. W. Cook, & J. I. Lacey (Eds.), Psychology and the problems of society (pp. 259–267). American Psychological Association.

Warren, J. (Apr 1971). BSPA still struggling to define relationship with APA. APA Monitor, 2(4), 1, 11.

Williams, R. L. (2008). History of the Association of Black Psychologists: Profiles of Outstanding Black Psychologists. AuthorHouse.

Williams, R. L. (2008). A 40-year history of the Association of Black Psychologists (ABPSi). Journal of Black Psychology, 40(3), 249-260.

CCHP Archival Collections:

Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues (SPSSI) Archives records

Western Psychological Association records