Giving the polypill to everybody above the age of 55 kills two birds with one stone: cardiovascular risk and preventive medicine. That's what the proponents of the polypill say. The medical establishment is in uproar. Here is why you should be, too. But for a different reason.

Giving the polypill to everybody above the age of 55 kills two birds with one stone: cardiovascular risk and preventive medicine. That's what the proponents of the polypill say. The medical establishment is in uproar. Here is why you should be, too. But for a different reason.We are typically sold on the notion, that heart disease and stroke have become today's major killer, for one simple reason: We live far longer than our ancestors of a hundred years ago, whose major cause of death were infectious diseases. Their eradication has brought upon us the blessings of longer lives, and with it the detriments of aging related cardiovascular disease. It's root cause is elevated cholesterol, a theory enshrined in the so-called lipid hypothesis. Questioning it is to the medical establishment what Galileo's theories were to the catholic church: plain heresy. After all, cholesterol lowering drugs, the statins, are a blessing to mankind and substantial reducer of cardiovascular death. This is what nearly everyone believes. The Chinese Tao has a quote for such situations. It goes something like this: "when everyone knows something is good, this is bad already." You might reject my suggestion that such ancient wisdom could possibly apply to modern medicine. So, let's get cracking at those facts which everyone knows.

Claim 1: Heart disease, stroke and cancer are today's major killers Undeniably. Cardiovascular disease accounts for roughly one in three deaths (30%), followed by cancer, which kills another one in four (23%) [1]. Which means your chance of dying of any one of those two clusters is fifty-fifty. By the way, these data, and the ones which follow, are drawn from U.S. statistics. Unfortunately they are typical for the rest of the developed world and pretty close to what the developing nations experience, too.

Claim 2: One hundred years ago, Infectious diseases were the main killers Yes, indeed. In 1900, one third of all deaths were due to tuberculosis and influenza alone.

Claim 3: Since we eliminated those infectious diseases we have a longer life expectancy and therefore we simply die of aging related diseases.

This is where it starts to get hairy. First, you must NOT confuse life expectancy with life span. Life expectancy is typically quoted as life expectancy at birth. It is an average value of all the years lived divided by the number of those born alive. You can imagine how this number is very sensitive to the rate of infant deaths and of deaths during the early adult years. Particularly when one third of all newborns die within the first 12 months. Which was a typical infant death rate, not only in ancient Rome but throughout most of modern history until the 17th century. While this infant mortality rate made Roman's have an average life expectancy at birth of a little less than 30 years, a considerable part of the population lived to their sixties and seventies. In fact, very few people will have died at age 30, most either having done so way earlier or much later. Back to 1900.

In 1900, U.S. females had a life expectancy at birth of 51 years, whereas those who reached 50 had a remaining life expectancy of another 22 years, to reach 72. Today these numbers stand at 80 years life expectancy at birth and 82 years at the age of 50. Which means two things: First, while life expectancy at birth has increased dramatically by more than 30 years over the past 100 years, life span hasn't increased that much. Second, life expectancies at birth and at age 50 have become virtually the same. The reason is a substantial reduction in infectious diseases, which killed considerable numbers of infants, of women giving birth, and of young adults. Which brings us to ...

Claim 4: Cardiovascular disease and cancer are diseases of old age, which is why they are more prominent today than 100 years ago.

When we compare today's death rates with those of the past, we need to keep in mind that the age distribution in 1900 was substantially different to what it is today. In 1900 there were a lot less people of age 65 and older than there are today. So, we need to answer the question, what would the CVD mortality have been in 1900 if the population had had the same age distribution as ours has today. Thankfully, the U.S. CDC provides us with a standardization tool, which allows us to answer this question. They simply use the U.S. population at the year 2000 as the standard to which all other population data can be standardized. The process is called "adjustment for age" and, when applied to mortality rates, they become truly comparable as so-called age-adjusted mortality rates. So, in the future, when you read something about mortality rates or disease rates, make sure to check which rates he uses for comparison. If he doesn't say which is which, you need to be very skeptical about his interpretation.

Now here comes the surprise: The mortality rate for cardiovascular disease in 1900 was 22% vs. today's 31%. At first blush, this doesn't sound that much different. But think about it: If CVD is merely the disease of old age, why should there be a difference at all? And if there is a difference, why should we be dying of this disease at a 50% higher rate when we have all the medical technology, and the statins, which our grand parents didn't have.

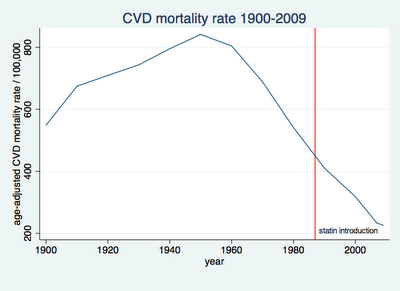

The entire issue becomes even weirder when you look at the development of the CVD mortality rate over the 11 decades from 1900 to today (Figure 1). CVD rose to a 60% prominence in 1960 before steeply falling to today's level. You can see that in the 1950s and 1960s people died of "age-related" heart attacks and strokes at a 50% higher rate than 50 years earlier. Another 60 years later we die at a quarter the rate of the 1960s. Which begs the question: What happened?

Figure 1

Actually, there are two parts to this question: If heart disease is age-related, why was there such a dramatic rise in age-adjusted mortality over the first half of the past century, when there should have been none. I have my theories, but I will keep them for one of my next posts.

Far more pertinent to this post's subject is the second part of the question: What did happen in the 1960s and thereafter? If you think the answer is "statins happened, stupid", then you are in for a surprise. The first statin to hit the market was Merck's Lovastatin. In 1987! Its the red vertical line in the chart of figure 1. Almost 30 years after CVD mortality rate began its steep descent. A descent, which did not accelerate with the introduction of statins to the market.

Now, don't get me wrong, I'm not saying statins do not reduce the risk of dying from CVD, or the risk of experiencing a non-fatal heart attack or stroke. There is quite some evidence to their benefits. My point is that, whatever statins do, they do not show up on our mortality radar as the grand reducer of CVD death. Not within the current medical practice of risk estimation and subsequent risk-based treatment.

Enter the proponents of the polypill, which contains a statin, a blood pressure lowering medication, and an aspirin. Are these proponents right to say, give a statin to everyone, who has hit the age of 55? Well, they have a point. Wald and colleagues ran a computer simulation to compare the most simple of all screenings, age, vs. the UK's National Institute of Health guidelines, which recommend screening everybody from age 40 at five-yearly intervals until people reach the risk threshold of a 20% chance of a cardiovascular event in the next 10 years [2]. That's the cut-off for treatment. Astonishingly, the benefits are virtually the same. What this screening routine buys at the costs for doctor visits and blood tests, we get free of charge with the age threshold.

This paper was so counterintuitive to the established way of medical thinking, that the authors' paper, first submitted to the British Medical Journal in 2009, went through a 2-years Odyssey of being rejected by 4 Journals and 24 reviewers, before finally being published in PLoS One in 2011.

But costs from a societal perspective are not the costs which interest you. You might be more interested to know, that even at an elevated risk of CVD, 25 people would have to swallow a statin for 5 years to prevent just 1 heart attack. How much larger will this number be, the number needed to treat (NNT), as we call it, if you are simply 55 but with no other CVD risk factor? You won't get an answer anytime soon. Big Pharma is not interested to finance a study, which could deliver the answer. They don't earn much money from polypills which only use generic statins, those whose patent protection has expired.

To me the NNT is definitely too high. I won't take the polypill, though I just crossed that age threshold a few days back. I pursue another path to health and longevity. And I believe, you might want to look at my reasoning for that path. I will introduce it progressively over the next few posts. Not that I evangelize it, not to worry. I simply believe there is a third alternative to the risk-oriented practice of preventive medicine and to the kitchen-sink approach of its polypill wielding opponents. This third alternative is heresy to both. But with heresy I'm in good company. Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis was a heretic when he suggested in the mid 1800s that the high rate of deadly childbed fever was due to physicians not washing their hands between dissecting dead bodies and helping women deliver their children. It took about 50 years for his ideas to become medical mainstream.

That's because new ideas become accepted in medicine not upon proof of being better than the old ones, but upon the old professors, who have built their careers on the old ideas, dying out. So, let's try to survive them.

1.Kochanek, K.D., et al., Deaths: Preliminary Data for 2009, in National Vital Statistics Reports 2011, U.S. Department of Health And Human Services.

2.Wald, N.J., M. Simmonds, and J.K. Morris, Screening for future cardiovascular disease using age alone compared with multiple risk factors and age. PLoS ONE, 2011. 6(5): p. e18742.