Megan Ramos and I started using intermittent fasting in the Intensive Dietary Management program sometime around 2013. At the time, the entire notion of fasting smelled faintly of quackery. The prevailing wisdom was that skipping meals was an entirely suicidal idea, from a weight standpoint. After all, everybody 'knew' that skipping meals would make you so ravenously hungry that you would be helpless to resist stuffing donuts by the box into your mouth.

Indeed, when we started, I had never heard anybody talk about fasting. It just sort of occurred to me one day that if you wanted to lose weight, then maybe just not eating was a good idea. I was a physician, and I ask people to fast all the time. When people go for surgery, they need to fast the night before. When people go for a colonoscopy, they need to fast for 24-48 hours. When people go for fasting bloodwork, they need to fast. So, I knew that fasting wasn't completely out of the question.

But nevertheless, my initial reaction to this thought was that it would never work. But then I paused. I thought to myself 'Why wouldn't it work?' There really was no reason. I also had a good understanding of human physiology and knew that the body stored fat in case there was nothing to eat. So, if we gave our body the chance, it would have to burn this fat that was so carefully stored. So, I set out to research it.

Treating patients with IF

So, we just started treating patients with various fasting protocols. And the results were simply stunning. We had patients reverse their long standing type 2 diabetes in mere months. We had patients lose hundreds of pounds. Not everybody did it, of course, but those that did, generally lost weight. After all, if you don't eat, you will generally lose weight. But everybody still thought I was crazy, batsh** stupid. I heard it from doctors. I heard it from dieticians. I heard it from nurses. I heard it from personal trainers.

Around then, I started giving lectures at Low Carb High Fat/ Ketogenic conferences. This was a few years ago, so most people thought eating lots of fat was really crazy. Ketogenic diets, since then, have become quite mainstream, with Keto cookbooks regularly in the best sellers lists. And in this room of 'crazy' dieters, people would look at me and think 'This guy is crazy'. My, my. How things have changed in a few short years.

Increasing interest

The same survey also found that people increasingly blamed sugar (33%) and carbohydrates (25%) for weight gain, which is almost double the percent that blamed dietary fat. In the 1990s any type of fat was considered fattening. We had low fat everything. But eating low fat foods like white bread, pasta and jellybeans certainly did nothing to help weight loss efforts to the amazement of the Dietary Guidelines people, who have continuously stressed fat reduction as their core message for good health. You can't fool people forever.

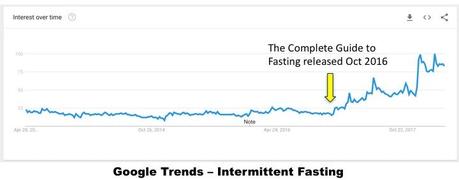

Google Trends shows the same increasing interest in intermittent fasting. Up to about 2016, when I wrote The Obesity Code and The Complete Guide to Fasting, there was a low level interest in the topic. After 2016, interest has grown significantly. There are more than 3 times the number of daily searches on the topic.

2018 seems to be the year that intermittent fasting is really catching the attention of the mainstream. An article in Good Morning America quoted Robin Foroutan, a registered dietician and spokesperson for the Academy of Nutrition and Dietitics, the main governing body for dieticians in the United States saying "It's nice when something is popular and actually safe". Wow. Fasting went from being a completely crazy idea in 2013 to a practice called popular AND safe by dieticians. Our own IDM program is building a community around helping others fast, and also providing personalized counselling.

Even respected academic institutions like Harvard have come around in their thinking. In a recent Harvard Health Blog, Dr. Tello wrote a 'surprising update' on intermittent fasting - it just might work. She quotes Harvard University's Dr. Wexler, Director of the Massachusetts General Hospital Diabetes Center "There is evidence to suggest that the circadian rhythm fasting approach, where meals are restricted to an eight to 10-hour period of the daytime, is effective".

The advice to eat 6 or 8 or 10 times a day and to always eat breakfast even if not hungry was never rooted in any science. There were no studies to show that this sort of advice actually worked. But if you don't eat, then people can't sell you products. So, eating all the time was good for business even if not good for your waist line. Repeated often enough, this advice to eat 10 small meals per day gained a sheen of respectability that was never deserved. If you are not hungry, then don't eat. That seems pretty logical. Instead, we believed, and told our children that "Even if you are not hungry, you must shove some granola bars into your mouth or you'll be unhealthy". Then we turn around and wonder we have a childhood obesity crisis.

My son, this week went to a school camp for robotics. On the parents information, they reassured me that they will provide my child with lunch and 2 snacks per day. ARGHH. Why does my child, or any child need 2 snacks? Yet, because it comes from the school means that we are indoctrinating our kids to believe they must eat constantly to be healthy. By contrast, in the 1970s, when I grew up, nobody, but nobody ate snacks. Obesity, not such a problem.