– Contributed by Rhonda Rinehart

Back in December we posted about a future Cummings Center building assessment being funded through an NEH grant. We were hopeful about this knowledge-gathering journey we were about to take, looking toward collections care and the significant part that the building will ultimately play in that role. After three whirlwind days learning about the bones and the guts of our building and how to make it healthier and stronger, we are preparing to make some changes.

Jeremy Linden from Linden Preservation Services spent three days onsite to get to know not just the building, but the collections, the staff, and even typical Akron weather patterns. The goal was to provide information about how all of these elements work together to create our current preservation environment. The assessment focused mostly on the basement where the majority of Cummings Center materials live. But to know what’s going on in the basement we needed to know what’s happening outside and around it as well.

Jeremy Linden illustrating cooling and heating zones in CCHP basement

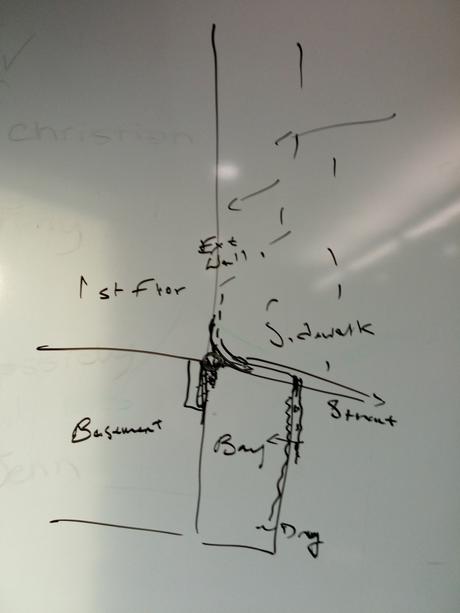

Linden’s illustration of southside structure of basement storage

The two central points of focus were the heating and cooling systems within the building and the basement foundation, or ‘envelope’. We learned how the building mechanical systems are configured, how they communicate with one another and with the university’s physical facilities staff, and the pathways individual HVAC units take throughout the building to provide CCHP spaces with our unique heating and cooling needs.

In addition to proper heating and cooling, archival storage spaces also require appropriate humidification and de-humidification for optimal collections preservation. How all of these components correspond to create the building’s interior environment led to the biggest surprise of Jeremy’s visit: how we handle our heating, cooling, and humidity in the basement has a direct impact on moisture coming into the basement walls. If the difference between interior and exterior environments is too great in an underground environment, moisture pressure or vapor is created as it moves through the walls to the lowest point. The telltale signs of this event are mineral salts, called efflorescence, on the walls from moisture left behind. Vapor pressure also causes spalling, or deterioration of the wall’s coating. So we need to be careful about how the basement environment reacts to our heating, cooling, and humidification efforts into the future.

White mineral deposits on basement walls due to efflorescence

Spalling as a consequence of vapor pressure

The good news is that we can take concrete steps toward short and long term improvements based on Jeremy’s findings. We’ll begin with a basement envelope study which will evaluate the condition of the building’s foundation and provide information on improving the basement environment.

Tools of the trade – thermal camera, moisture meter, temperature and relative humidity meter

Thermal imaging to detect water leaks, moisture seepage, and structural integrity of a CCHP basement pipe

Spending three days learning about the environment that we work in and care for our collections in was a significant move toward improved collection stewardship. Thanks to the NEH grant, we know more than we did before about our building and its systems, and we feel more confident in our journey forward.

We are excited about our next steps. After completing the building envelope study, we are planning a design study that will guide a significant renovation to the Archives of the History of American Psychology. This will guide us in future renovations that will provide our unique collections with a home with room for growth and the capacity for state-of-the-art preservation.