Cancer has been recognized as a disease since the time of the ancient Egyptians. Ancient manuscripts from the seventeenth century BC describe a "bulging mass in the breast" - believed to be the first description of breast cancer. The Greek historian Herodotus, writing around 440 BC describes Atossa, the queen of Persia who suffered from an illness likely to be inflammatory breast cancer. In a thousand year old gravesite in Peru, mummified remains show a bone tumor. So cancer dates back to antiquity, but it was likely very rare, given the shorter life expectancy of the time. But the cause was unknown, mostly blamed on bad gods.

In the second century AD, the Greek physician Galen used the term oncos (swelling) since cancers could often be detected as hard nodules under the skin, in the breast, etc. It is from this root that oncology, oncologist, and oncologic are all derived. Galen also used the suffix -oma to denote a cancer. Celsus (ca 25 BC - ca 50 AD) a Roman encyclopaedist who wrote the medical text De Medicina, translated the Greek term 'karkinos' into 'cancer', the Latin word for crab.

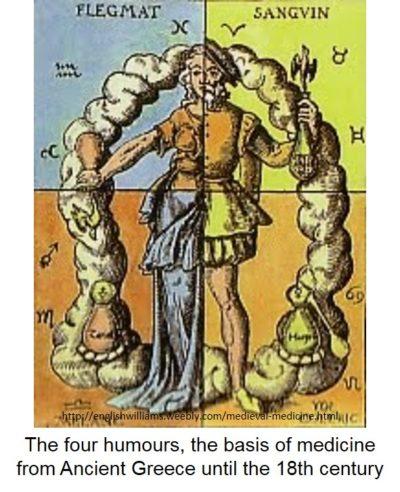

When attempting to understand the cause of disease, the ancient Greeks were firm believers in the Humoral Theory. All diseases resulted from an imbalance of the four humours - blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile. Inflammation was the result of too much blood, pustules - too much phlegm, jaundice - too much yellow bile.

Cancer was considered an internal excess of black bile. These local accumulations of black bile would be seen as tumours, but the disease was a systemic disease of the whole body. Treatment, was therefore aimed at removing this systemic excess, including those 'oldies but goodies' blood letting, purging and laxatives. Local treatments like excision would not work because it was a systemic disease. Again, a surprisingly insightful comment into the nature of cancer. This spared many a cancer patient surgery, which was a pretty gruesome thing in ancient Rome. No antiseptics, no anesthetics, no analgesics - yikes.

By the 1700s, Lymph Theory took the spotlight, developed by Hoffman and Stahl. The liquid parts of the body (blood and lymph) are always circulating throughout the body. Cancer was believed to occur whenever lymph did not properly circulate. Stasis and then fermentation and degeneration of lymph was believed to cause cancer.

By 1838, the focus moved to cells rather than fluids with the Blastema Theory. The German pathologist Johannes Muller showed that cancer was not caused by lymph, but instead originated from cells. It was later shown that these cancer cells derived from other cells.

With this realization that cancers were simply cells, doctors began to imagine that they could cure cancer by cutting it out. With the advent of modern anesthesia and anti-sepsis, surgery had been transformed from a barbaric ritualistic sacrifice to a fairly reasonable medical procedure. But there was a problem. The cancer would inevitably come back, usually at the resected surgical margin. If there was any cancer visible left after surgery, the damned thing would invariably come back. In the 1860s, cancer surgeries had become more and more radical and extensive hacking away more and more normal tissue to remove all visible tumor.

William Halsted, a surgeon working on breast cancer thought he had a solution. Cancer is like a crab - sending microscopic pincers out into the adjoining tissue which are not visible, leading to inevitable relapse. Well, why not simply cut all possible tissue affected even if there was no evidence of involvement. This was called 'radical' surgery, from the original Latin meaning of 'root'.

This does have a logic to it. A radical mastectomy, to remove the breast and all the surrounding tissue might be disfiguring and painful, but the alternative was death. It was a misguided kindness. Dr. Halsted collected his results and in 1907 presented them to the American Surgical Association. Patients whose cancer had not spread to the neck or lymph nodes did very well. But those with metastatic spread did poorly and how extensive the surgery was irrelevant to the overall outcome. Local disease did well with local therapies like surgery.

Around the same time, in 1895, Röntgen discovered X-rays - high energy forms of electromagnetic radiation. It was invisible, but could damage and kill living tissue. By 1896, barely 1 year later, a medical student, Emil Grubbe tested this new invention on cancer. By 1902, with the Curies discovery of radium, more powerful and precise x-rays could be developed. This brought up the tantalizing possibility of blasting cancer with X-rays and the new field of radiation oncology was born.

The same problem as had befallen surgical attempts at cure became obvious. While you could destroy the local tumor, it would soon recur. So, a local treatment, surgical or radiation could only treat early disease, before it had spread. Once spread, it was too late for such measures.

So the search was on for systemic agents that could kill cancer. What was needed was something that could be delivered to the whole body - chemotherapy. The first solution came from an unlikely source - the deadly poison mustard gases of World War I. This colourless gas smelled of mustard or horseradish. In 1917, the Germans lobbed artillery shells filled with mustard gas at British troops near the small town of Ypres. It blistered and burned the lungs, and the skin, but also had a peculiar predilection for selectively destroying parts of the bone marrow, the white blood cells. Working with chemical derivatives of mustard gas, scientists in the 1940s began to treat cancers of the white blood cells, called lymphomas. It worked, but only for a time.

Once again, the lymphoma would improve, but inevitably relapse. But it was a start. The concept had at least been proven. Other chemotherapeutic agents would be developed, but all had the same fatal flaw. Drugs would be effective for a short period of time, but then inevitably lose effectiveness.

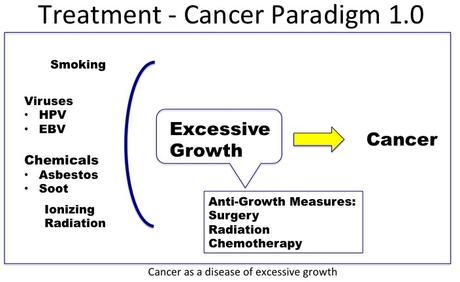

Cancer paradigm 1.0

This, then was Cancer Paradigm 1.0. Cancer was a disease of uncontrolled cellular growth. It was excessive and haphazard eventually damaging all the surrounding normal tissues. It happened in all different tissues of the body, and often spread to other parts. If the problem was too much growth, then the answer is to kill it. This gave us surgery, radiation and chemotherapy, still the basis of much of our cancer treatments today.

But this Cancer Paradigm 1.0 suffers from a fatal flaw. It did not answer the question of what was causing this uncontrolled cell growth. It did not identify the root cause, the ultimate cause. The treatments could only treat the proximal causes and therefore were less useful. Local diseases could be treated, but systemic disease could not.

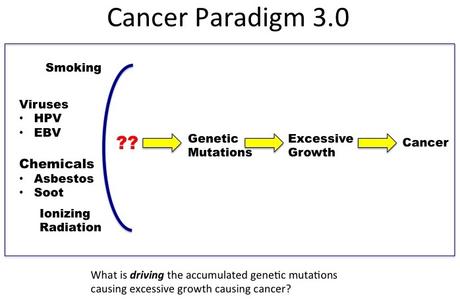

We know that there are certain causes of cancer - smoking, viruses (HPV), and chemicals (soot, asbestos). But we didn't know how these were related. Somehow these various diseases all caused excessive growth of cancerous cells. What the intermediary step was unknown.

So doctors did the best they could. They treated the excessive growth with relatively indiscriminate killing of cells that are growing quickly. And it worked for some cancers, but failed for the majority. Nevertheless, it was a step.

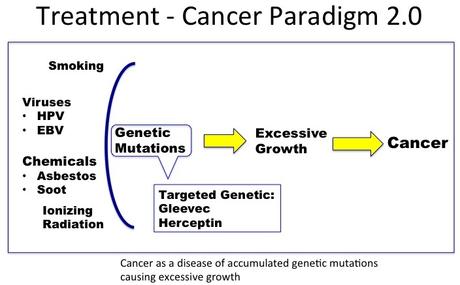

Cancer paradigm 2.0

The next big event was Watson and Crick's discovery of DNA in 1953 and the subsequent discovery of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. This would usher in Cancer Paradigm 2.0 - Cancer as a genetic disease. Once again, we had a list of known causes of cancer and known excess growth of cancer cells. According to the somatic mutation theory (SMT) all of these varied diseases causes genetic mutations which caused the excess growth.

We were bravely trying to peel back the layers of the truth. In addition to all the treatments of Cancer Paradigm 1.0, this new cancer paradigm as a genetic disease led to new treatments. Gleevec for chronic myelogenous leukaemia and Herceptin for breast cancer are the most well known treatments and the most notorious successes of this paradigm. These are major advances in treatment for relatively minor diseases compared to the totality of cancer. This is not to downplay their benefits, but, as a whole, this paradigm has failed to live up to its hype.

Most cancers, as we've discussed before, have not been affected. Cancer mortality continues to increase. We know that cancers have many, many genetic mutations. The Cancer Genome Atlas proved that without a doubt. The problem was not finding the genetic mutations, the problem was we were finding too many mutations. Different mutations even within the same cancer. Despite huge investments of time, money and brainpower into this new genetic paradigm, we've not seen the commensurate benefits. The genetic defects were not the ultimate cause of the cancer - they were still only an intermediary step, a proximate cause. What we need to know is what is driving those mutations.

As the sun is setting on Cancer Paradigm 2.0, a new dawn breaks over Cancer Paradigm 3.0. Since the early 2010s, realization is slowly percolating that the genetic paradigm 2.0 is a dead end. The National Cancer Institute reached out beyond the usual cadre of researchers and funded other scientists to help think 'beyond the box'. Cosmologist Paul Davies and astrobiologist Charley Lineweaver were eventually invited to develop the new atavistic paradigm of cancer.

This, too, may not be the ultimate cause we are searching for, but at a minimum, we can expect new treatments, and new discoveries. Stay tuned...

Do you want to read more by Dr. Fung? Here are his most popular posts about cancer: