A word about chronic illnesses.

It’s not always easy to conceive of addiction as a complex disease—but it’s getting easier. There are certain similarities among chronic diseases. As with diabetes, asthma, and high blood pressure, drug addiction often requires protracted and multi-faceted treatments—treatments that typically do not produce the kinds of dramatic cures and breakthroughs that are associated with recovery from other kinds of medical conditions.

As we become increasingly comfortable with the concept of addictive disease, we risk losing sight of a crucial distinction between acute medical disorders, like infections and broken bones; and chronic disorders with multiple biological, psychological, and social components, like diabetes and addiction.

William L. White of Chestnut Health Systems, and Thomas McClellan, Executive Director of the Treatment Research Institute and until recently the deputy director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) in the White House, co-authored a paper for Counselor Magazine that seeks to make the distinction clear. In “Addiction as a Chronic Disorder,” the two seasoned treatment professionals point out that “chronic care has to be quite different from acute care,” and that all treatments for chronic diseases like diabetes and addiction have three things in common:

1) They reduce symptoms but cannot affect root causes. Such treatments “do not return the affected individual to normal.”

2) They require major changes in lifestyle and behavior for maximum effectiveness. For example, “even if individuals with diabetes regularly take their insulin as prescribed, this will not stop disease progression if they do not also reduce sugar and starch intake, increase exercise and reduce stress levels.”

3) Due to their complex nature, “relapses are likely to occur in all chronic illnesses. Increasingly, family members are being trained to also provide continued monitoring, “ the authors point out.

So far, so good. But chronic care treatment is not what addiction treatment in America is really about. Addiction treatment in both medical and private settings is frequently governed by acute care thinking—the “broken bone” model of treatment. For example:

--“Services are delivered ‘programmatically’ in a uniform series of encapsulated activities (screen admission, a single point-in-time assessment, treatment procedures, discharge, brief ‘aftercare’ followed by termination of the service relationship).”

--“Services transpire over a short (and historically ever-shorter) period of time, usually as a function of pre-arranged, time-limited insurance payments.”

-- “The individual/family/community is given the impression at discharge (‘graduation’) that ‘cure has occurred.’”

-- “Post-treatment relapse and re-admissions are viewed as the failure (non-compliance) of the individual rather than potential flaws in the design or execution of the treatment protocol.”

Some fifteen years ago, the acute care model began to fall under increasing scrutiny as the neurosciences took wing and insights related to chronic diseases of the body and brain began to accumulate. As White and McClellan are at pains to point out, heavy drinking and other forms of drug abuse do not inexorably become chronic disorders. "Many substance use problems are developmental and as such are often outgrown in the successful transition from adolescence into adulthood. Others occur in tandem with major life transitions (e.g., death of a loved one, divorce, job loss) and are resolved by time, natural support, brief professional intervention or peer-based intervention by others in recovery."

It’s the same with high blood pressure: A period of hypertension may or may not lead to a chronic condition, and at present it’s difficult to predict whose high blood pressure is likely to prove resistant to changes in diet, exercise, and weight.

Beyond the matter of treatment, what do chronic diseases like asthma, diabetes, and addiction really have in common?

--They are influenced by both genetic and environmental risk factors.

--They have “a prolonged course that varies from person to person in intensity and pattern.”

--They are accompanied by “risks of profound pathophysiology, disability and premature death.”

--They have effective treatments, and “similar remission rates, but no known cures.”

If substance dependence is like other chronic illnesses, then two important insights follow: 1) “Acute care models of intervention for severe substance dependence may reduce substance use temporarily but those reductions are not likely to sustain once care stops,” and 2) “methods used in the treatment of other chronic illnesses might be effectively adapted to enhance long-term recovery from substance dependence.”

In the end, the authors argue that acute forms of treatment applied to a chronic disorder “offer an explanation of the generally high and rapid rates of relapse following cessation of most available addiction treatments: there is simply no quick fix for the most severe forms of this disorder.”

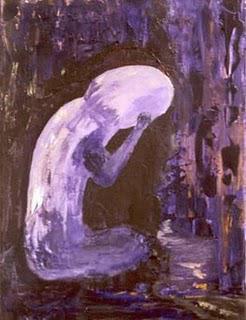

Graphics Credit: http://www.mdjunction.com