For those who are vegetarians, the idea of cooking with meat replacement might pop up some days when running out of cooking idea. Also, the sales of vegetarian food has risen up these days in the wake of horsemeat scandal because our appetite for processed meat products has reduced drastically. Some say: “It’s enough to change you into a vegetarian.”

For those who are vegetarians, the idea of cooking with meat replacement might pop up some days when running out of cooking idea. Also, the sales of vegetarian food has risen up these days in the wake of horsemeat scandal because our appetite for processed meat products has reduced drastically. Some say: “It’s enough to change you into a vegetarian.”

Imitation meat products come in various types from ‘pepperoni’, ‘lamb-style roast’ and ‘meat-free turkey’ to ‘fish-style steaks’, ‘duck’ pate and veggie ‘mince’.

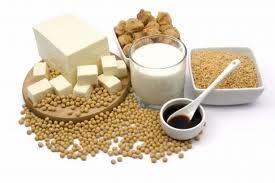

The main ingredient in mock meat products is made from highly processed types of soya flour, called ‘isolate’ or ‘concentrate’. It is labelled as vegetble protein, textured vegetable protein or soya protein.

The use of these soya ingredients isn’t restricted to meat lookalikes.

Even if you aren’t a meat avoider, you are almost certainly eating soya in a number of products, from cheese spreads and non-dairy creamer to protein bars and ice cream.

Study the label on a ready-made beef burger, for instance, and you will often find it contains soya protein isolate — a cheap filler to bulk out the meat.

The soya bean is cultivated worldwide, with the biggest supplies coming from the U.S. and Brazil.

Once the oil has been extracted, the solids that remain are processed to obtain pure protein.

Until the Eighties, soya protein was seen merely as a by-product of the soya oil industry, but then U.S. soya companies set about making it more profitable by promoting it as a health food.

They claimed eating soya could give you stronger bones, control symptoms of the menopause (hot flushes and night sweats) and make you less likely to develop breast, colon and prostate cancer.

These claims were largely based on research sponsored by the soya companies and on epidemiological studies that show associations between things.

For instance, because rates of heart disease are lower in most Asian countries than in western ones, soya companies argued this was because Asian people consumed more soya.

Soya was marketed as a wonder food, the Orient’s remedy for the West’s health problems.

However, the health virtues attributed to soya were soon challenged by researchers.

In 2006, for example, an American Heart Association review of a decade-long study of soya’s supposed benefits cast doubt on the ‘heart healthy’ claims and concluded that soya did not reduce hot flushes in women or help prevent cancer.

A study at Massachusetts General Hospital’s infertility clinic in 2008, where men were asked to consume various soya products, including tofu, veggie burgers, soya milk and protein shakes, found ‘higher intake of soya foods is associated with lower sperm concentration’.

The jury is out on the long-term health impact of eating soya, but there are reasons to be wary.

Soya beans contain naturally occurring toxins. These include phytic acid, which reduces our ability to absorb essential minerals, such as iron and zinc, and might therefore cause mineral deficiencies, and trypsin inhibitors, which impair the body’s capacity to digest protein.

These toxins are also found in other foods, such as chickpeas and wheat, but at lower levels.

Processing soya is designed to substantially reduce or remove these toxins, but traces may remain.

Soya also contains isoflavones — potent plant compounds that mimic the female hormone, oestrogen.

In 2011, the European Food Safety Authority’s scientific panel dismissed claims made by the soya industry that isoflavones helped hair growth, eased menopause symptoms, supported heart health and protected cells against oxidative damage.

It concluded a cause-and-effect relationship between consumption of soya products and health benefits ‘had not been established’.

Meanwhile, there have been suggestions that, far from being protective, eating too much soya protein can be harmful because of its hormonal effect.

In 2003, the UK government’s Committee on Toxicity identified three groups where evidence suggested there might be a potential risk from consuming large amounts of soya: babies fed on soya-based formula, people with an under-active thyroid and women diagnosed with breast cancer.

But the industrial nature of soya protein manufacture also raises concerns.

While some soya foods, such as tofu, miso, soya milk and yoghurt, are lightly processed, pure soya proteins — the sort you might find in a veggie sausage or vegan cheese — are commonly extracted by washing soya flour in acid in aluminium tanks.

This raises the possibility that aluminium, which is bad for the brain and nervous system, can leach into the product.

Another potential concern is the chemical solvent hexane — a component in glue and cement — is used to extract the oil from soya beans. It is known to poison the human nervous system.

Through repeated exposure, people can develop neurological problems similar to those experienced by solvent abusers.

The soya industry claims only trace residues of hexane find their way into the finished product.

Processing also frees up glutamic acid from the soya, a substance that can trigger allergic reactions.

Soya is one of the eight most common food allergens, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

A further issue with many soya products is not the soya itself, but what is added to it.

As soya protein is pale, odourless and almost taste-free, many manufacturers rely on sweeteners, artificial flavourings, salt and colourings to make their products more appealing.

So the irony is that in trying to avoid meat, vegetarians may be buying products with as many additives and industrialised ingredients as are found in cheap, processed meats.

But can soya really be so bad when Asian populations have been eating it for centuries, with no apparent problem?

It’s true that popular ingredients such as soy sauce and miso feature prominently in oriental cuisine.

But the soya in these products, when traditionally prepared, has been fermented, using time- honoured methods.

These involve soaking the beans, adding natural bacteria to encourage fermentation and a lengthy ageing process.

All this helps neutralise toxins in the beans.

So traditionally made, fermented soya foods are a different animal from modern soya proteins, which are produced using a fast-track chemical method.

Asian cultures also include soya in their diets in a different way from those in the West. Asian people don’t drink pints of soya milk each day as we do (think of all those soya lattes you hear people ordering in coffee shops).

Nor do they rely on soya as their main protein source.

In China, a vegetable dish containing a small amount of tofu would be just one element in a meal that featured meat or fish, and lots of veg.

We are far from fully understanding the impact of modern soya protein consumption.

As this ingredient has been in our diet for only three decades, there is no track record of safe use.

But while we await the answer, it may be wise to be cautious.

Source: Daily Mail