contributed by Anthony Pankuch and Arianna Iliff. Anthony is an undergraduate student assistant, and Arianna is a graduate student assistant at the CCHP.

Last Monday, the World Health Organization released an early version of the upcoming ICD-11 to the public, the first major revision of the organization’s health and disease guidelines in 18 years. Included in this edition are two victories for the LGBTQ community: the removal of gender identity disorder and the reclassification of gender incongruence, alterations made with the expressed intent of destigmatizing the lives of transgender and non-binary individuals.

This change comes five years after the removal of the gender identity disorder diagnosis from the DSM, a similar diagnostic manual utilized exclusively within the United States. Traditionally, the DSM has followed in the footsteps of the ICD, changing to reflect the latter publication’s broader directions. So why has this dynamic seemingly been reversed with the subject of gender identity?

The DSM-I, shown in an exhibit at the National Museum of Psychology. This first edition, published in 1952, categorized homosexuality as a “sexual deviation” and a “sociopathic personality disturbance.”

Diagnoses of homosexuality and gender identity first appeared in the ICD in 1948 and 1965, respectively. Both homosexuality and “transvestitism,” as it was then labeled, were categorized as sexual deviances. Their inclusion validated purported “cures” for homosexuality and gender non-conformance, including drug and electroshock therapies, castration, and lobotomy.

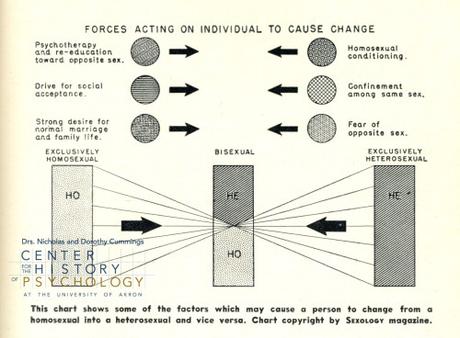

Popular psychology magazines such as “Sexology” sought to find both causes and cures for the “deviation” of homosexuality. Source: Ludy T. Benjamin Popular Psychology Magazine Collection.

The DSM-II, published in 1968, followed with matching diagnoses. However, with the rise of gay and transgender activism in the United States (remembered notably through the 1969 Stonewall Riots), the American publication became embroiled in controversy. A major protest against the American Psychiatric Association in 1970, combined with the efforts of researchers like Evelyn Hooker (1907-1996), led to a 1973 revision of the DSM-II and the gradual removal of homosexual diagnoses in the following decades.

Since then, the DSM has tended to be one step ahead of the ICD in diagnosing sexuality and gender identity. Psychology is a science of immense societal implications and an agent of social change, given its ability to classify and often stigmatize entire livelihoods. Even today, following the release of the ICD-11, activists have expressed a desire for further changes to the diagnosis of gender incongruence. The shifting nature of the DSM’s outlook on LGBTQ identities reminds us of this human element to psychology. The science, built upon a desire to better understand our human nature, continues to thrive not just through lab methods, but also through engagement with a diverse range of human perspectives.

The National Museum of Psychology features a unique exhibit on researcher Evelyn Hooker and the evolving diagnosis of homosexuality within the DSM.

This is the first in a series of blogs regarding the relationship between sexuality, gender identity, and psychology. Watch this space for additional posts.

Citations:

Branson, Helen Kitchen. “Can we prevent HOMOSEXUAL DEVELOPMENT?” Sexology, Nov. 1954, 245.

Drescher, Jack. “Queer diagnoses revisited: The past and future of homosexuality and gender diagnoses in DSM and ICD.” International Review of Psychiatry, vol. 27, no. 5, 2015, pp. 386-395. http://ezproxy.uakron.edu:2048/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2016-08809-004&site=ehost-live

Herek, Gregory M. “Sexual Orientation Differences as Deficits: Science and Stigma in the History of American Psychology.” Perspectives on Psychological Science, vol. 5, no. 6, 2010, 693-699. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/41613587.pdf