Drug treatments for marijuana withdrawal.

Drug treatments for marijuana withdrawal.Sometimes it’s easy to forget that marijuana is the most widely used illegal drug of all. We demonize it, yet we take it for granted. We punish citizens for its possession, but we call it a “soft” drug.

The idea of marijuana as an addictive drug--for some but by no means all users—still seems preposterous to a large number of recreational pot smokers. Yet these same people have far less trouble dealing with the existence of raging alcoholics surrounded by a majority of controlled, recreational drinkers or non-drinkers.

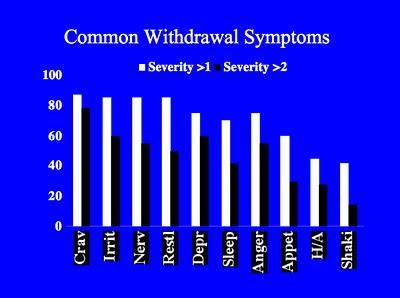

For purposes of this post, we are going to stipulate that sufficient scientific evidence now exists to include marijuana in the category of addictive psychoactive drugs. Heavy, daily users of marijuana sometimes find themselves in an unexpected bind if they decide to quit cold. Perhaps as many as one or two in every ten heavy pot smokers will find themselves suffering from flu-like symptoms, loss of appetite, insomnia, vivid dreams, irritability, generalized anxiety, and other side effects that can be at least as unpleasant as quitting cold turkey after a long cigarette habit.

Why didn’t we know this earlier? Perhaps for the same reasons that we didn’t know until the 1980s, as a general piece of knowledge, that cocaine was highly addictive. (Marijuana Anonymous didn’t start up until 1989). Doesn’t that sound absurd now, the state of our understanding of cocaine’s effects only 30 years ago? For people who suffer strong and repeatable withdrawal symptoms when they try to quit smoking weed, it is equally absurd to proclaim that what they are wrestling with does not resemble a genuine drug addiction (See the Addiction Inbox thread on marijuana withdrawal, which is now approaching 1,000 comments, and which constitutes a major database of self-reported data on marijuana withdrawal).

Having identified marijuana as classically addictive for a small slice of the user population, the focus has lately turned toward human laboratory studies, although most of the human studies thus far have been open-label trials rather than controlled double-blind studies. A group of researchers at Columbia University has been testing a variety of medications in search of a compound with demonstrated effects on marijuana abstinence and withdrawal. A study published online last year examines the effectiveness of a variety of medications on the course of marijuana craving and withdrawal in users classified as marijuana dependent. In other words, they are looking for the equivalent of a nicotine patch for marijuana.

In an article for CNS Drugs, Ryan Vandrey of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and Margaret Haney of the New York State Psychiatric Institute, surveyed such studies as presently exist on the subject of pharmacotherapy for cannabis dependence. There are presently no clinically validated treatments for marijuana withdrawal. And, unlike the hundreds of controlled, double blind trials of pharmaceuticals for addiction to alcohol, cigarettes, cocaine, and heroin, recent research on medications for marijuana dependence has been sparse and scattershot.

In an article for CNS Drugs, Ryan Vandrey of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and Margaret Haney of the New York State Psychiatric Institute, surveyed such studies as presently exist on the subject of pharmacotherapy for cannabis dependence. There are presently no clinically validated treatments for marijuana withdrawal. And, unlike the hundreds of controlled, double blind trials of pharmaceuticals for addiction to alcohol, cigarettes, cocaine, and heroin, recent research on medications for marijuana dependence has been sparse and scattershot.Nonetheless, the marijuana withdrawal syndrome is now well established in the scientific literature, as well as anecdotally. Among heavy dope smokers, the authors write, cold-turkey cessation from marijuana “produces cellular changes in the brain reward pathway (increased corticotrophin-releasing factor, decreased dopamine) that have been linked to the dysphoric effects associated with withdrawal from drugs such as alcohol, opiates, and cocaine, and are thought to contribute to relapse.”

What have they discovered so far?

One obvious starting point was dronabinol, a.k.a. Marinol, the government-approved synthetic THC often prescribed for nausea, vomiting, and appetite loss due to chemotherapy. Marinol is a direct approach to the nicotine patch strategy: A substance that stimulates cannabis receptors in a manner similar to, but by no means identical with, the high produced by natural marijuana. Perhaps a regular low dose of Marinol would keep the cannabis cravings at bay among problem users trying to quit. As it turns out, not really. Some studies showed that you could reduce a pot addict’s withdrawal symptoms somewhat in a home environment with Marinol, but the dose required to accomplish this was high enough to represent potential problems of its own.

Another obvious candidate for investigation was rimonabant, a.k.a. Accomplia—but for the opposite reason. Rimonabant, which started out life as an anti-obesity medication, blocks the cannabinoid receptor CB1, so in that sense it should function roughly like Antabuse for alcoholics. It is the “anti-weed,” but as it turned out, rimonabant’s effect on cannabis receptors didn’t do the trick, either. Rimonabant “reduced the effects of smoked cannabis in two studies,” Vandrey and Haney write, “but a reduction of subjective drug effects was not consistently observed.” Furthermore, rimonabant is under suspicion for causing “adverse psychiatric effects” and is not much in favor at present.

Next up, naltrexone—an opiod receptor antagonist, which blocks the effects of heroin and is used in alcohol and heroin detox and withdrawal. Naltrexone has been shown in some studies to “reduce the subjective effects of cannabinoids in humans,” the authors note. But no dice: “In cannabis users, pretreatment with high doses of naltrexone (50-200 mg) failed to attenuate, and in some cases enhanced, the subjective effects of dronabinol and smoked cannabis.” To make matters worse, “the effect of naltrexone can be overcome with higher doses of cannabis.”

Other possible anti-craving drugs for marijuana have not been as rigorously studied. An open-label investigation of buspirone, which works on serotonin and dopamine systems, caused a decline in self-reported cannabis use, and pot smokers showed marked decreases in craving and irritability—but, as these things often go, buspirone was not well-tolerated by the participants, with too many dropouts due to adverse side effects.

Lithium, a mood stabilizer commonly prescribed for bipolar disorder, has shown promise in several small studies. An open-label lithium trial by the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre in New South Wales resulted in “significant reductions in symptoms of depression and anxiety and cannabis-related problems.” More studies are needed.

Fluoxetine, better known to the world as Prozac, has been anecdotally associated with reduced marijuana use in depressed alcohol-dependent patients, but has never been the subject of any large clinical studies with a population of users whose primary drug is marijuana.

And finally, there is a dark-horse candidate, a treatment drug sometimes employed to prevent relapse in cases of heroin addiction. Lofexidine is an alpha-2-adrenergic agonist that has been in use for years in the U.K. under the name BritLofex to treat the common symptoms of heroin withdrawal, such as cramps, chills, sweating, loss of appetite, and diarrhea. Similar but less intense withdrawal symptoms also afflict heavily addicted marijuana users. In a 2008 paper published in Psychopharmacology, “lofexidene was sedating, worsened abstinence-related anorexia, and did not robustly attenuate withdrawal, but improved sleep and decreased marijuana relapse.” Lofexidine combined with THC yielded even better results.

It appears that immediate research might be most profitably focused on lofexidine and lithium. And indeed, additional studies of the two drugs for cannabis dependency are planned by NIDA. Also, the combination of dronabinol and lofexidine appears to be worth pursuing in future clinical investigations of anti-craving drugs for marijuana.

Vandrey, R., & Haney, M. (2009). Pharmacotherapy for Cannabis Dependence CNS Drugs, 23 (7), 543-553 DOI: 10.2165/00023210-200923070-00001

Graphics Credit: http://archives.drugabuse.gov