~ contributed by Nichole Orchosky based on her Capstone project for completion of the Museums & Archives Studies certificate. Know Thyself serves as an intro to an online exhibition Nicole has also prepared.

Toward the end of the 1700s, a young Franz Joseph Gall sat in a schoolroom and glanced around at his fellow classmates. Gall caught on to a trend that fascinated him–he noticed that the students with excellent memorization skills often had prominent eyes and large foreheads. This discovery led Gall to hypothesize that the physical structure of one’s head may correspond to one’s personality traits in consistent and predictable ways. As Gall grew older he began to lecture on the subject, he expanded his theory into the science of phrenology, which quickly gained traction in Europe before spreading overseas to America by way of Gall’s own student Johann Kaspar Spurzheim [1].

Image credit: Smithsonian Institution Archives, Smithsonian Institution. “Smithsonian Learning Lab Resource: Franz Joseph Gall 1758-1828).” Smithsonian Learning Lab, Smithsonian Center for Learning and Digital Access, 25 Nov. 2016.

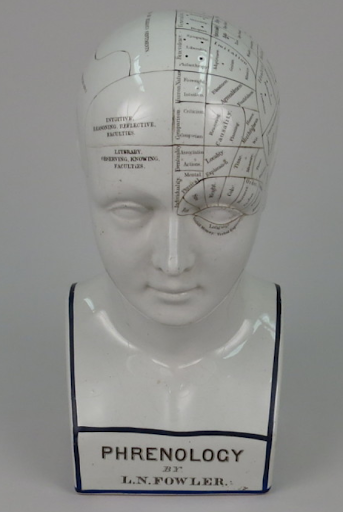

Phrenology, now considered pseudoscience, was widely popular in the 19th century among the general public as a way to make sense of human behavior. Middle class Americans were drawn to phrenology as one may be drawn to the predictions of astrological horoscope. They took comfort in the notion that something as unpredictable and subjective as the human psyche could now be quantified by a series of cranial measurements. The skull was divided into regions called “organs,” and the physical measurement of an organ would determine if you exhibited more or less of the personality trait corresponding to that organ. Gall theorized that the more developed the trait, the larger the organ, and the larger a protrusion it formed in the skull [1].

Image credit: National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. “Smithsonian Learning Lab Resource: Phrenology, By L. N. Fowler.” Smithsonian Learning Lab. 29 Jan. 2020. Smithsonian Center for Learning and Digital Access. 06 Dec. 2020.

As soon as brothers Orson and Lorenzo Fowler learned of the theory from visiting lecturer Spurzheim, they turned Phrenology into their life’s passion and joined with fellow phrenological enthusiast Samuel R. Wells to establish America’s most prominent phrenological hub, The Phrenological Cabinet in New York City [2]. The storefront functioned as a museum, medical office, and publishing house all in one. Busts, both real and replica skulls, and phrenological diagrams and literature were displayed and sold here. Anyone could walk in and have their own skull measured and examined to gain a better sense of self as well as discover ways in which they could correct their negative behaviors. Magazines like The Phrenological Journal and Life Illustrated were published and distributed here, including writings by the Fowlers themselves, who spent much of their time lecturing about their theories all over the country.

Image credit: Fowler and Wells families papers, #97. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

While the Fowlers gallivanted around America on lengthy lecture tours, who was left to take care of the family business? Samuel R. Wells oversaw the publishing side of The Phrenological Cabinet, but it was primarily the three men’s wives who took on the managerial and sometimes medical responsibilities within the office. Phrenology allowed women a sense of autonomy by allowing them a better understanding of their own mind and body, and for many women phrenology was a socially acceptable entry point to begin to seek out scientific knowledge. Abigail Fowler-Chumos, wife of Orson Fowler, became “Orson’s business manager, property manager, publisher, and phrenologist-in-training” [3]. Charlotte Fowler Wells, wife of Samuel Wells and sister to the Fowlers, “was the firm’s longstanding and highly respected business manager” and was even known as the “Mother of Phrenology” [3]. Lydia Fowler Wells, wife of Lorenzo Fowler, “was the second woman to receive an M.D. in the USA, after [British] Elizabeth Blackwell,” making her the first American woman to receive an M.D. [4]. When it came to the business of phrenology, middle-class American women were not only the number one consumers; they ran the show.

Image credit: “The Late Mrs. Lydia F. Fowler, M. D.” Wheaton College, c. 1880. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lydia_Folger_Fowler.jpg#metadata

During the Civil War, women stepped up to run their households in their husbands’ absences. Women were not about to let go of their newfound autonomy during the following Gilded Age, and phrenology was one of the earliest scientific fields in which women could practice and participate. You would be surprised to learn how progressive the Fowlers were as they “combined the business of phrenology with the work of reform, linking the science to temperance, dress reform, diet reform, water-cure and women’s rights” [4].

You can learn more about phrenology and women’s role in the field in the “Know Thyself” virtual exhibition.

Thirteen complete issues of The Phrenological Journal and Life Illustrated are now available as digital editions of the Ludy T. Benjamin, Jr. Popular Psychology Magazine Collection.

Sources Used:

- Morse, Minna Scherlinder. “Facing a Bumpy History,” Smithsonian Magazine, 1997 Oct. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/facing-a-bumpy-history-144497373/

- “Orson S. Fowler,” The Phrenological Journal and Life Illustrated, Vol. 84-85, pp. 196-198.

- Lilleleht, Erica. “‘Assuming the Privilege’ of Bridging Divides,” History of Psychology, vol. 18, no. 4, 2015, pp. 414-432.

- Bittel, Carla. “Woman, Know Thyself: Producing and Using Phrenological Knowledge in 19th-Century America,” Centaurus, 19 April 2014, pp. 104-130.