In the morning, the train ride is refreshing. The air seems cool as it whips through the wagons, and we fly by slums where people go about bathing from buckets, brushing their teeth and hanging clothes.

As a volunteer with One! International, I agreed to visit the school in Nallasopara twice a week. The journey begins before 7:00 am when my alarm would go off, the only time I needed an alarm; after that, the sounds and smells of my neighbourhood would do the trick just as well. I would wash my face, squeeze into a tunic to cover my bottom and put on my dirty shoes. Nothing clean survives Nallasopara. After I stuff a 2L bottle of water in my bag, I head down to the end of my street where the garbage pile swells and shrinks daily, and I catch a rickshaw ride to the Bandra station. There, the crowds begin.

I meet a young gentleman there, the appointed volunteer body guard. He is a young man of 19 years, very conscious of his style and appearance. He would often be sporting a freshly pressed shirt and sunglasses. I always wondered how he obtained such distinct crease lines in his shirts since his residence was the school in Khar, no official laundry services available. Indians are resourceful. Once, I saw him fiddling with his sunglasses and noticed the temple was bent. I took them from him and attempted to realign the parts, to no avail.

We trail up the stairs, through the buzzing crowds and find our way to the platform. If there’s time, we have chai. When the train comes, he sees me to the ladies’ first class compartment and waves farewell. “Nallasopara,” he reminds me. That’s where I will see him next.

If I’m lucky, there is a seat available. Usually in the morning, there is. I can see through the metal grating into second class. It’s always crowded.

Indian women are peculiar. Even when an entire carriage is empty, there is almost always one who insists on sitting directly beside me. Apparently, I’m infringing on her personal space, how dare I. Sometimes, I move, sometimes I’m stubborn.

The train heads north.

We eventually get past the real city limits of Mumbai and blow our way into countryside. Green! I see a river and pastures, and children playing cricket in fields, real fields! I smell something other than garbage and pollution.

The relief is short-lived, however. Only a couple of stops later is our arrival at Nallasopara. All other station stops seem quiet and vacant by comparison. I sling my backpack on my front, queue up at the train door behind the ladies who appear to be getting off as well. That’s the trick: find the Indians who look like they are going where you are, and then follow their surge. You will never get anywhere on your own. Even before the train stops, people are trying to get on.

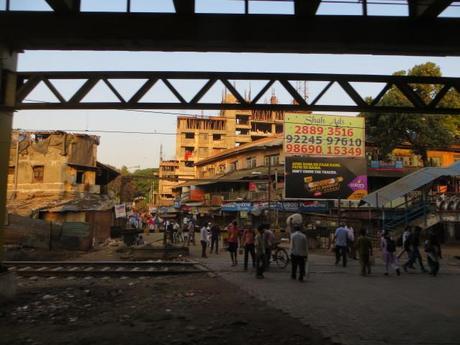

Sights like this are not uncommon:

Amazingly, in the crowds, the volunteer guardian finds me when we arrive. Finding the one bobbing white person in the crowd is not so hard, I guess. And trust me, I was the only one (so long as there were no other volunteers with me, which was often the case). Nallasopara is not a place where tourists or foreigners go.

In the morning, the station is humming with people going places, selling vegetables, selling pieces of cloth. My bodyguard had great foresight when he bought one such piece and tied it around his face later, just like a bandito. I wish I had understood sooner, so I could have bought one for myself. Nallasopara is dusty.

There are puppies playing and cows weaving through the crowd. On one or two occasions, the cows appeared to be on the same morning commute as all the humans.

Once we carve our way through the crowds, we make it to a dusty street. The young gentleman guiding me negotiates a rickshaw ride. We sit in the back. Often, if it’s just the two of us, other people jump on as well. If it’s a man, my body guard ensures he sits between us. If it’s a woman, it’s alright if he sits in the front with the driver, and she sits with me. Sometimes two people sit up front with the driver and link arms in order to stay on the rickshaw.

The rickshaw ride is dusty and bumpy. We go past shops and people and construction and animals. Trucks kick up rocks and dust and spew out fumes. If I have a scarf with me, I cover my nose and mouth. My body guard is already prepared with his handkerchief.

We often fit up to 7 people in one rickshaw. Between linking arms and creative seating arrangements, we manage. The whole ride takes anywhere from 10-20 minutes. In the heat, which by this point is beginning to set in, the jolting ride can feel like forever.

At our stop, we get out of the rickshaw. There are a few stares from the Indians here; it’s nothing but a wide street, with trucks and rickshaws and animals going by, but for the most part, unlike at the station, the Indians from this area are used to seeing white people.

We begin walking. This is what that walk looks like:

I’m told that during monsoon, these dusty streets are like rivers, and you can imagine what is flowing through the water. This is India, after all. And yes, volunteers are still required to go twice a week.

After this walk that takes about 10 minutes, we arrive at the school, and suddenly it’s all worth it.

There’s a chorus of children shouting “GOOD MORNING DIDI!”

The days in Nalla are hard. For me, the foreigner who suffers in such extreme heat, I melt away while I’m here. Almost every day, the power cuts out, leaving us with no fans to circulate the hot air. The classrooms become ovens. Temperatures are always at least 5 degrees Celsius higher up here. The school in Khar is cool by comparison. In Nalla, there is no running water. I must drink the water I’ve brought with me or buy more bottled stuff while I’m here. Often, I can drink 2L or more and never have to pee. To wash my hands, there is a huge drum of water at the door, and a shared chunk of soap. I’m reminded over and over not to drink this water, even though the children often do. There are two bathroom stalls in the courtyard. Toward the end of my stay in India, someone broke one of the doors, and that brought the stall count down to one. In that heat, and shared between all those little bodies, that squatter was anything but charming. I’ll let your imagination take you away. If any volunteer is going to get sick with Delhi belly, it’s here.

After a couple of visits, the other two volunteers give Nallasopara the name “Nallasoproblem”.

After a full day of teaching classes, sometimes 5 or 6, with class planning and marking assignments and tests, it’s time to go home, home being back to Bandra. I do this whole post in reverse: dusty walk, stares and goats in the street. Bumpy, dusty rickshaw ride – stacked with people in 40C weather. Sweat, pollution, dust. More dust. Arrive at the train station, no shade in sight. I can feel myself baking. Fight to get on the train, pray for a seat. Sometimes I can’t find the first class compartment in time and end up in second class. This means standing with my face in some lady’s armpit and being groped all over. At least it’s just ladies. No personal space in India. Arrival in Bandra. The surge and push of crowds going home. Find my body guard once more. Stand in line for a rickshaw and head back to the volunteer apartment. Proceed to collapse.

It’s no wonder I was so exhausted at the end of these days in Nallasopara.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Have you ever been to Nallasopara? Tell me about it!