–Contributed by Charity Smith

With Dr. Zimbardo’s upcoming visit to CCHP right around the corner (Oct. 5th, see website for details), you’d think I’d go the easy route and write about the Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE). Check! Another item off my to-do list. Ok, admittedly, that’s pretty much what I intended to do…but then I got to thinking: how could my little blog post possibly compete with hearing about the SPE, straight from Zimbardo himself? Let’s face it, it couldn’t.

In searching for a new angle, I discovered that Zimbardo is the 2015 recipient of the Kurt Lewin Award—the namesake of which, is the very man whose groundbreaking research on group dynamics laid the foundation for both the SPE and Milgram’s (1963) famed (READ: infamous) obedience study. Here enter, Kurt Lewin—father of modern social psychology, pioneer researcher of human interactions, and psychologist extraordinaire. Thwarted again, my words cannot compete with those of Zimbardo, who so accurately and succinctly heralded Lewin as “probably the most influential figure in all of social psychology,” (1985).

Lewin, a Jewish immigrant who left Germany in 1933, posited that our behaviors are not simply inherent to our nature; they are the result of an interaction between ourselves (and all the contextual baggage that entails) and environment. This concept is woven throughout Resolving Social Conflicts: Selected Papers on Group Dynamics, a text published posthumously by Lewin’s wife in 1948. Divided into three sections and spanning Lewin’s work from 1935 to 1946, the text explores group dynamics, belongingness, and cultural oppression.

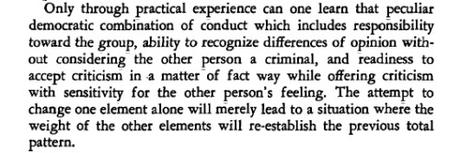

Part I, “Problems of Changing Culture,” explores what is needed for a culture to make effective and lasting change, particularly in relation to Germany and WWII. Perhaps the best synopsis of Lewin’s theories on conflict resolution (not to mention some timeless advice for all of us) comes from an amalgam of two articles, both found in this first section:

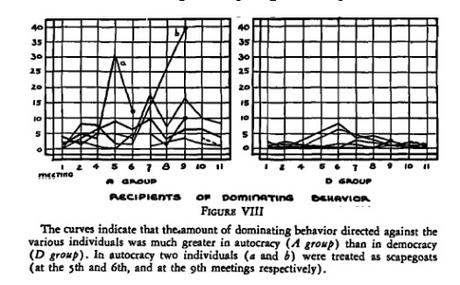

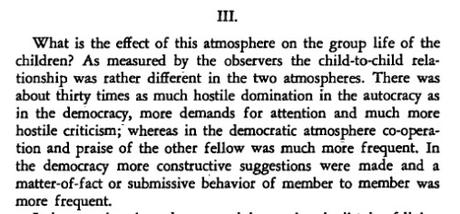

Part II, “Conflicts in Face-to-Face Groups,” Lewin discusses the impact of leadership styles on tension, conflict resolution, and behaviors resulting from group membership. Although he cites research on children, the below table and discussion of autocratic and democratic governance provides more than just the study’s findings. These results, which mirror the stark contrast between German and American rule, serve as a reminder of the space Lewin’s research holds in time: WWII.

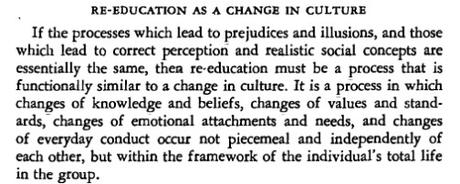

Part III, “Inter-Group Conflicts and Group Belongingness,” largely centers on the impact of prejudice and segregation on Jewish people during WWI and WWII. Spanning 1935-1946, and heavy with Lewin’s own views and minority status, these articles make salient the weight of oppression and contain concepts that are, sadly, timeless. Below he proffers both the problem and the solution:

Although I didn’t go the route of the SPE, the opportunity to read Lewin’s book brought to light the atrocities of the most horrific prison experiment of all: The Holocaust. With articles that explore this time period on a personal, psychological, and sociological level, Lewin not only defines how social evils arise, but provides us with a road map back to the humane.

Lewin, K. (1948). Resolving social conflicts: Selected papers on group dynamics. New York: Harper & Bros.

Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral study of obedience. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67, 371-378.

Zimbardo, P. G. (1985, June). Laugh where we must, be candid where we can. [A conversation with Allen Funt.] Psychology Today, 19, 42-47.