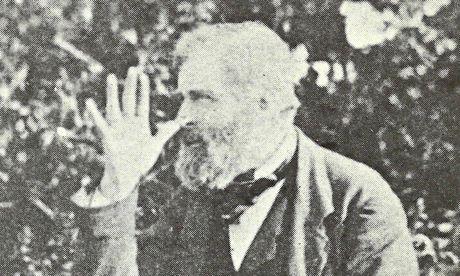

It really was awfully bad form of Master William Shakespeare not to vouchsafe further and better particulars of his life so as to satisfy my intuitive guess (need?) that he was a man after my own heart, the sort of chap with whom I could happily quaff a pint or two of ale in my local pub, The Tippling Philosopher. Regretfully, along with everybody else, my fond thoughts are exactly that - fond, in the Shakespearean sense meaning daft or loopy. The fact is that we know precious little of the man who seemed able to speak in a thousand voices. However, much of what we do know is due to an eccentric Victorian scholar whom today might well be described as 'a volume short of a library'! Thanks to Charles Nicholl at 'The Graun' I learned more about this oddity who did so much for Shakespearean scholorship - James Orchard Halliwell-Phillipps. Here he is in a typical pose which he entitled: 'My reply to the idiots who ask me to resume literary studies':

Rather than literary studies, what Mr. Halliwell-Phillips concentrated upon was collecting Shakespearean artifacts which he mostly stored in a ramshackle property formed from small, ready-made Victorian bungalows linked by corridors which a visitor described as looking like "a squatters' camp in South Africa". Not the least of the treasures he unearthed was a hoard of documents from Stratford. As Mr. Nicholl tells it:

What he laboriously uncovered and transcribed was a wealth of fragmentary detail touching on Shakespeare's "other" life as a provincial landowner and family-man – the property deals and minor lawsuits, the pressurising of debtors, the hoarding of malt, the quarts of claret and sack disbursed to a visiting preacher – and out into the penumbra of family associations stretching from his yeoman grandfather Richard Shakespeare to his childless granddaughter and last lineal descendant, Elizabeth Barnard. Much of what he found could be called prosaic, but this was precisely the stuff he relished. His aim was to grasp a sense of the daily, mundane texture of Shakespeare's life. This ran counter to the general adulation – almost deification – of Shakespeare that had taken hold in the later 18th century, particularly after the bicentennial of 1764 orchestrated by the actor David Garrick. According to James Shapiro's book Contested Will, it was the apparent disparity between these two identities – "between Shakespeare the poet and Shakespeare the businessman; between the London playwright and the Stratford haggler" – that blew up that great bubble of fruitless conjecture known as the "authorship controversy", launched on an unsuspecting world by Delia Bacon in 1856.

As a result of this eccentric man's almost pathological search for Shakespearean detritus (which included, mind you, one of only two original quarto editions of Hamlet from 1603!) we can now place our hero-worship into perspective and recognize that great poet and playwright and philosopher though he was, he was also a money-grubbing bourgeois not above profiting from some careful market-fixing who would sue your arse off if you owed him money! In other words, were you to meet him for a pint of ale in your local, you would be buying the drinks!