It's alright, you can tell the 'Memsahib', she's quite used to me being in love with other women. I suppose it began with the very young Brigitte Bardot and I haven't looked back since. The only problem with my multiple, nascent love affairs is that the other party never reciprocates. In this particular case I think the reason is probably because the lady is dead - and has been for a century and half!

Ada Lovelace - and you would have to love her for her name apart from anything else. Here she is:

Ada was actually born Augusta Ada Byron and she was the daughter of that rapscallion poet, romantic and adventurer, Lord Byron. He and his wife seperated immediately after Ada's birth and she never had contact with her father again not least because he died when she was eight. In due time she married and produced three children. By and large it was a good-ish marriage but Ada was a very modern woman for her time and she might well have indulged a few naughtinesses - such a pity I wasn't around!

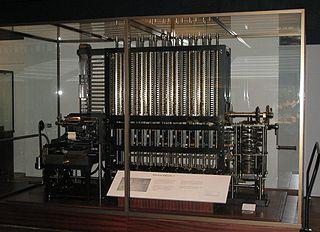

However, as James Gleik (yes, it's him again!) reminds us in his superb book The Information, Ada was a very considerable mathematician who moved easily in the highest scientific circles of her time. She struck up a friendship with Charles Babbage who was desperately trying to bring his 'difference engine' to full fruition. Babbage was one of the very greatest of the Victorian polymaths but amongst the many schemes and visions he had, his desire to produce a fully automatic calculating machine was pre-eminent. Ada threw herself into the work and messages between them would criss-cross London several times a day and night. Alas, she died desperately early of a hideously painful cancer and Babbage's machine never quite took off. What a cruel fate for two such brilliant people, both able to sense the future but both born too early to have the means to bring it about.

The London Science Museum's difference engine, built from Babbage's design. The design has the same precision on all columns, but when calculating polynomials, the precision on the higher-order columns could be lower. The Engine is not a replica (one was never built during Babbage's lifetime); therefore this is the first one - the original.

(And don't ask me what "polynomials" are!) Anyway, as I have mentioned before, she was, I think, the inspiration for Tom Stoppard when he wrote his superb play Arcadia and invented the character of young Thomasina Coverly, a scientific genius before her time. And, yes, I'm in love with her, too!