As a family doctor with a low-carb clinic, I see ultrasound reports of non-alcoholic fatty livers on an almost daily basis. It's no surprise, though, because the patients who enroll at my clinic have type 2 diabetes and/or are overweight for the most part. Those are the two most important risk factors in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. I actually like to see those reports, and I'll tell you why further down.

When I ask my patients, what did the radiologist say to them during the ultrasound, they invariably say "He/She told me to stop drinking alcohol or to eat less fat. But doctor, I don't drink, and I've been eating low fat all my life!". Yes, I know. Eating low fat is what got your liver in trouble in the first place...

My friend Dr. L'Espérance is a radiologist who has been low carbing it years before I even knew anything about it. When she does an ultrasound for a fatty liver follow up, she always asks her patients what did their family doctor say about them having a fatty liver. Invariably, they answer "He/She told me to eat less fat"...

It's unfortunate we don't work in the same region or with the same patients!

Human foie gras and carbs

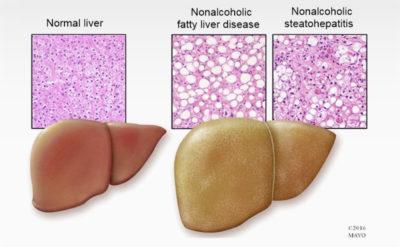

It's a common misconception that eating fat will make your liver fat.

It's actually and mainly the carbohydrates that are the cause, in particular the fructose.

It's worth reading about insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, as well as the metabolism of fructose, to really understand why ( Carbohydrate intake and NAFLD: fructose as a weapon of mass destruction, and Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a clinical update).

I ask my low-carb patient to get an abdominal ultrasound at the beginning of their low-carb journey, and six months later, at the end of our program. I like documenting a fatty liver in my patients' files because I know it will get reversed, for most people, in most cases.

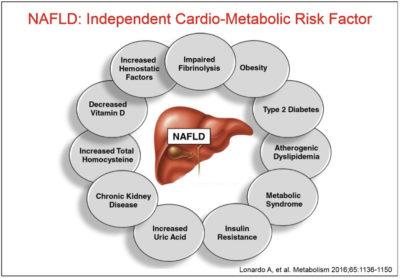

Also, it's not necessarily common knowledge that fatty liver disease is an independent risk factor for cardiometabolic disease.

Fatty liver disease also increases insulin resistance, which contributes to hyperinsulinemia. It's an on-going process that does not tend to generate specific symptoms, so patients are not always aware of their situation. The end-result can be type 2 diabetes.

Fatty liver disease can also progress into steatohepatitis, in which the liver is actually inflamed. This can progress to cirrhosis, and even liver cancer.

A concrete sign

For the majority of my patients, having a fatty liver is something a lot more tangible than, say, an abnormal lab result. So, when they see on paper that their liver steatosis has been reversed, it helps them realize how much healthier their body has become on a low-carb diet. They don't just look and feel good on the outside; their organs look better and work better in the inside!

For the practitioners out there, who do not have access to abdominal ultrasound for all of their patients in whom they suspect a fatty liver, a calculator can be used. This calculator can also be used to know which patients should be sent for an ultrasound, and which should be counseled on diet and other risk factors.

On a side note, let me point out that I generally expected to have elevated ALT's in my patients with hepatic steatosis. However, it turns out that the vast majority of my patients with a fatty liver have normal liver enzymes.

A risk calculator

Here is the calculator that can be used with patients at risk: Fatty Liver Index risk calculator, from the Liver Research Center, in Italy ( The Fatty Liver Index: a simple and accurate predictor of hepatic steatosis in the general population)

You can download the Excel worksheet and enter your patients' data, and it will automatically calculate a score for you. This index is based on the following parameters:

There is a table to interpret the scores, but to sum it up:

- ≥ 60 => 78% probability of liver steatosis

- < 20 => 91% probability of no liver steatosis

Aside from an ultrasound and a score calculated using the FLI above, you can also suspect or diagnose a fatty liver with the following:

- Elevated liver enzymes (ALT, AST, GGT) (although normal results don't necessarily indicate a normal liver)

- FibroScan

- Computer Tomography (CT scan)

- Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS) and Magnetic Resonance Imagery (MRI)

- Liver Biopsy (costly procedure, difficult to implement on a large scale and not without risk for the patient)

Now, what about treatment?

There are currently no drugs to improve or reverse liver steatosis. But you can be certain that they are looking for such drugs.

This might sound paradoxical, but as a doctor, one of my least favourite solutions to a health problem is prescribing a drug. Especially when the health problem is caused by lifestyle habits.

But my least favourite option of all for a lifestyle-related health problem is definitely surgery.

Yes, you can reverse fatty liver disease with bariatric surgery. But that should be the very last option on the list, after everything has been tried.

You can also reverse fatty liver disease with a significant weight loss (around 8 to 10% of body mass), with severe caloric restriction. But if you tank your metabolism in the process, you might still be in trouble.

You can improve your insulin resistance with moderate to intense physical activity and strength training, which will help improve liver steatosis.

Or you can try eating a well formulated low-carb or ketogenic diet, love what you eat and not feel constant hunger anymore. As a side effect, you will likely lose weight, but you will also reverse chronic diseases associated with lifestyle habits, such as fatty liver.

"Low-carbohydrate high-fat diet has been shown to be effective in improving all the abnormal clinical and biochemical parameters of metabolic syndrome and NAFLD in multiple studies. These dietary interventions are also associated with weight loss in patients. Even without significant weight loss, however, lifestyle interventions were found to improve NAFLD, especially if patients are adherent to the changes." ( Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a clinical update)

Basically, let's not blame the butter for what the bread did.

If you or your patients have fatty liver disease, why not give a go at eating low carb? It's certainly worth a good try, before contemplating any other more drastic measure.

-

Dr. Èvelyne Bourdua-Roy