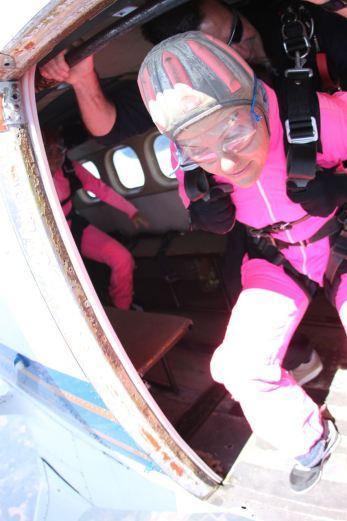

About to make my first jump

Everyone approaches risk a little differently. While one person might balk at the thought of riding a roller coaster, another might dream of jumping off the top of the structure with only a wingsuit and a single parachute and fly over fairgrounds.

One man’s thrill is another man’s day at the beach.

But it’s not only individuals that differ in their approaches to risk. Communities do as well. In researching my new book on risk and reward in action sports, I’ve had the chance to meet some very interesting people and talk to them about not only why they love their sport but also how they mitigate the risks.

What strikes me is the way communities that surround a certain sport all seem to have similar approaches to mitigating risk. Skydiving, for example, might seem like a very risky sport. Standing on the lip of an open cockpit, the wind buffeting your chest and blowing hollows into your cheeks while your heart struggles to leap out of your jumpsuit feels quite risky. It feels like you’re about to jump to your death, like you’re about to make a terrible mistake. Only adrenaline junkies and reckless thrill-seekers do this kind of thing, you tell yourself. At least that’s how it feels on your first jump.

But meeting skydivers and reading accounts of participants, I’ve found the opposite to be true. Skydiving, and the off-shoots such as speedflying and wingsuit flying, require precision and accuracy. Skydivers are not reckless; nor are they living off an adrenaline rush. Instead, they are careful, calculated, and abhorrent of those taking too many risks. In a way, skydivers are some of the most risk-averse group of action sports athletes I’ve met. They also encourage others to take personal responsibility for their training, their jumps and their actions.

Extreme kayaking has progressed rapidly in the past decade. With the advent of shorter, more maneuverable boats, kayakers are now hucking off waterfalls that a few years ago would have been considered unrunnable. According to extreme kayaker and filmmaker Josh Neilson, younger boaters are now performing tricks and drops that it took years for their older brethren to master. Kayaking is a sport with some barriers to entry. First of all, you must have an instructor. Few people could jump into a boat and start out on a Class IV river. Along with the equipment comes boating partners. This is not a solo sport; so the veterans teach the newbies the rules of the river. Moreover, there’s a worldwide community of kayakers very keen to keep their reputations intact. Whether in online forums or face to face in the eddy, veterans will remind aspirants not to go too big too fast lest they all be labeled reckless risk-takers.

Skiers, on the other hand, are different. Perhaps because the sport of skiing grew up within resorts, where operators managed some of the risk for their customers, skiers were never encouraged to take things slowly. Instead, skiers and snowboarders are lauded for how big they go. Sponsorships, film shoots and contests go to the ones with the biggest cajones, the skiers and riders willing to try the gnarliest lines.

The sport of skiing has progressed to a point where skills are not quite matching the conquests. Now that fat skis, rockered tips and beefy touring bindings allow people to ski steep spines that a few years ago would have been reserved for the pros, everyone can be a hero. They can even capture it all on their helmet cam and post the event straight to Facebook before they even unstrap their bindings. Unlike some of the other action sports communities, the skiing world rarely censors such acts.

But things may be changing.

Robb Gaffney, psychiatrist, skier, and author of Squallywood and creator of G.N.A.R. or “Gaffney Numerical Assessment of Radness” has a new project. Through his website, Sportgevity.com, Robb hopes to continue pushing the sport while also maintaining longevity for athletes. When I spoke to Robb recently, he told me that when we get positive feedback for hanging it out there, our identity gets wrapped up in that; we are destined to make mistakes. Robb is tired of hearing the trite conclusion, “he died doing what he loved.” Instead he wants to change the way we approach our sports. So far his website is doing just that, with videos and articles aimed at building judgment and maintaining a rational head while pursuing our various sports.

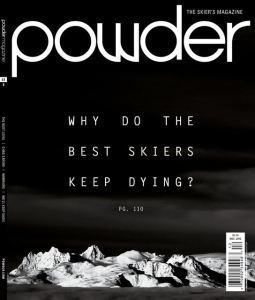

The cover of the December 2012 issue of Powder Magazine asked a stark question, “Why do the Best Skiers Keep Dying?” In that article Matt Hansen claims that the “level had gotten so high, the commitment so fierce, that any little mistake, stroke of bad luck, or curveball from Mother Nature proved fatal.” It’s important to know when

It seems the time is right to have a discussion about skiing and risk. Perhaps the greater community will take part by encouraging more thoughtful reflection.

How do we as a ski community enjoy the sport, even progress the sport, without killing ourselves or attending yet another memorial service? Here are a few ideas:

- Take personal responsibility. I recently wrote a post about this over at blogcrystal.com and how it relates to skiing in our inbounds avalanche terrain at Crystal.

- Remember why we’re doing it. We ski and snowboard because it’s fun. We ride powder for the pure joy of carving plastic and metal and fiberglass through snow. In order to ski big lines, we need to choose the right conditions. We need to ask ourselves whether it’s really necessary to ski that one big line. Would it make it any more fun? Would the day be any bette? If yes, then take precautions, choose the right day and go for it when you’re ready.

- Keep your head. I’ve seen skiers on a powder day as they wait in line for first chair, their eyes circling in a crazed state that borders on scary. They’ve spent the better part of the morning to be there, sacrificed sleep and possibly breakfast and told themselves repeatedly that all the effort would be worth it. That no matter what, they will find powder that day. Which brings me to my last point.

- We as a community need to promote thoughtful reflection and judgment. No more, “powder at all costs” attitude. Because the costs have gotten too high. Instead, we could take on Dan Hogan’s line that he said last year on a busy day while riding the gondola. Granted, Dan got a lot of powder days last year. But on that particular day, he just shook his head at all the rudeness going on around him. It was as if all the skiers and riders on that busy Saturday could only be happy while skiing pristine powder. The rest of the day, the remaining 90% of it, was just wasted it seemed. Dan declared to all that would listen, “It’s all good, man,” and lifted his hands to take in the entire gondola, the hordes cramming the slopes below him and the powder getting ripped to shreds below us. It’s all good.