Written by Ludy T. Benjamin, Jr.

“America is Suffering from an Outbreak of Psychology.” Those words were written in 1924 by Stephen Leacock, Canada’s Mark Twain. Leacock wrote in the March issue of Harper’s Magazine:

In the earlier days this science was kept strictly confined to the colleges … It had no particular connection with anything at all, and did no visible harm to those who studied it…All this changed. As part of the new researches, it was found that psychology can be used…for almost everything in life. There is now not only psychology in the academic or college sense, but also a Psychology of Business, Psychology of Education, Psychology of Salesmanship, Psychology of Religion… and a Psychology of Playing the Banjo…For almost every juncture of life we now call in the services of an expert psychologist as naturally as we send for an emergency plumber. In all our great cities there are already, or soon will be, signs that read “Psychologist – Open Day and Night.”

(Leacock, 1924, pp. 471-472)

Although we are not sure that there was a Psychology of Playing the Banjo, psychology was a very popular topic in 1920s America as evidenced by hundreds of books and magazines on the subject, as well as psychology clubs that were formed in most large cities and in many smaller ones.

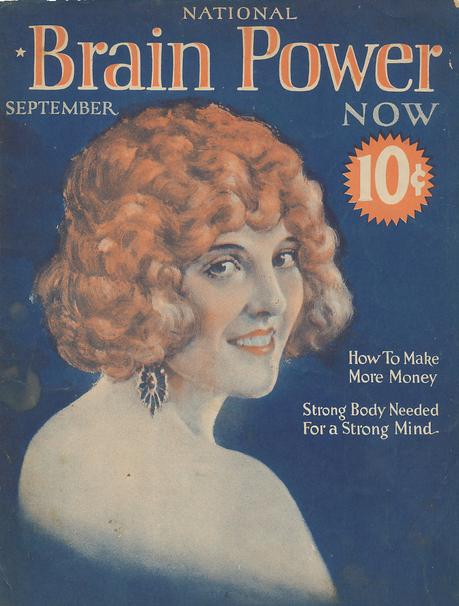

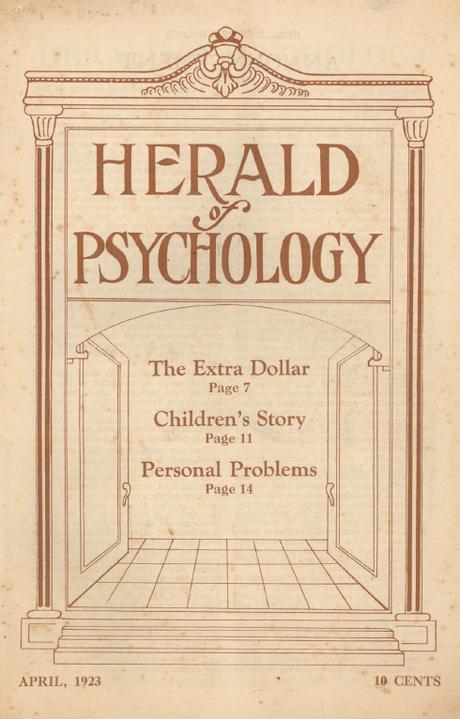

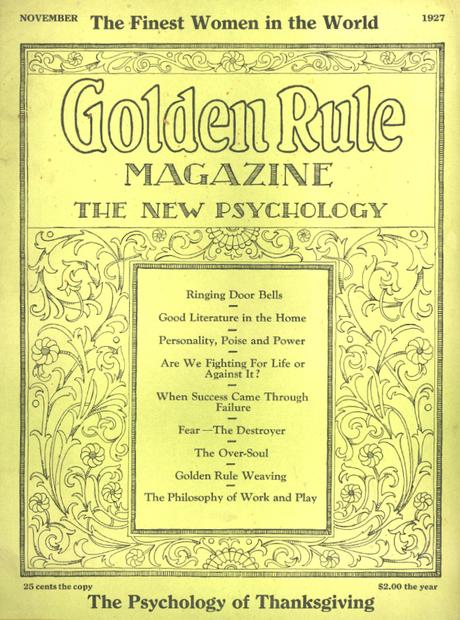

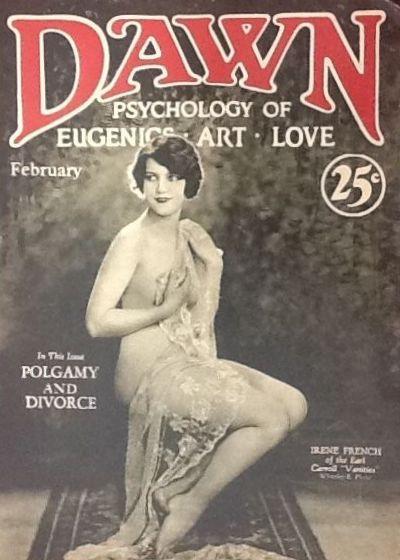

There were at least 15 popular psychology magazines that began publication in the United States in the 1920s. These included such titles as Herald of Psychology, Mind Power Plus, National Brain Power, Personality, Popular Psychology, Practical Psychology, Self-Realization, and Super-Psychology: The Mind Culture Magazine.

Brain Power, Sept. 1923; Herald of Psychology, April 1923; Golden Rule, Nov. 1927; Dawn, Feb. 1928

Many of these magazines were published for only a few years, and some even less than a year. The most popular magazine began monthly publication in April, 1923, a little more than a century ago. It was titled Psychology: Health Happiness Success. Its founder and editor was Henry Knight Miller (1891-1950) a Methodist minister in Brooklyn, New York, who, after recognizing the popularity of his self-help sermons, decided to leave his pulpit and launch a new magazine. Miller, echoing the popular writers of his time, touted the value of scientific psychology for health, happiness, and success. He wrote:

In Psychology magazine we have been applying the principles of scientific psychology to the actual problems and needs of human life. We have sought to build up a sound synthetic psychology, taking what is valid from all schools of psychological thought, simplifying it in expression and applying it to the problems of personal life.

(Miller, 1923)

Miller believed that there was much value in the new scientific psychology of the universities but that psychology professors were not writing about their work in such a way that the public could find it useful. So Miller vowed that he would take the most useful of this science and translate it into language that could be easily understood and prescriptions that could be followed to achieve the health, happiness, and success that his magazine promised. In actuality there was very little of scientific psychology that found its way into the pages of Miller’s magazine. Academic psychologists did not write for this magazine, nor did they write for the other popular psychology magazines of the time. Very few of Miller’s authors had any higher education degrees in psychology.

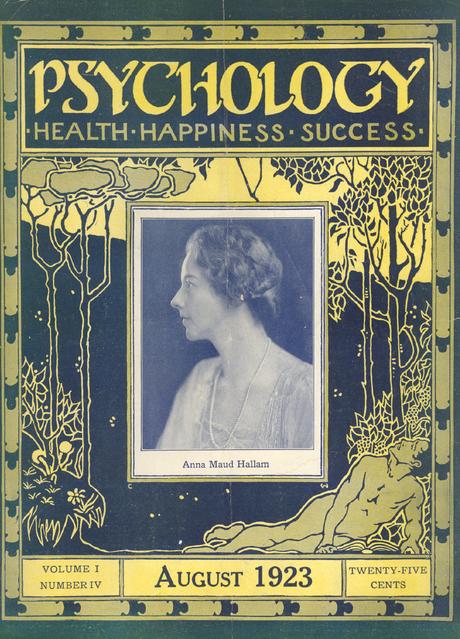

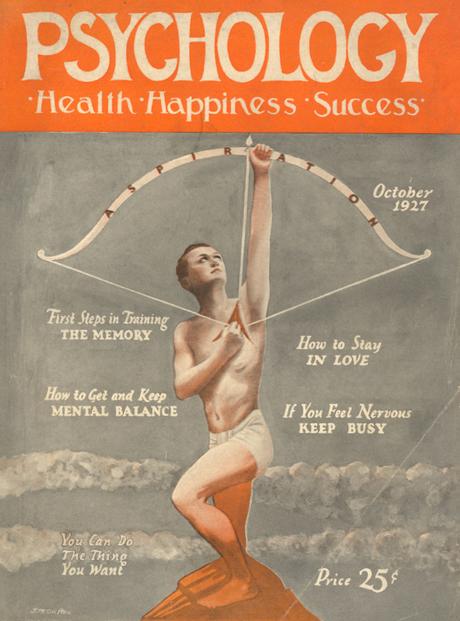

Two issues of Miller’s magazine: August 1923 and October 1927

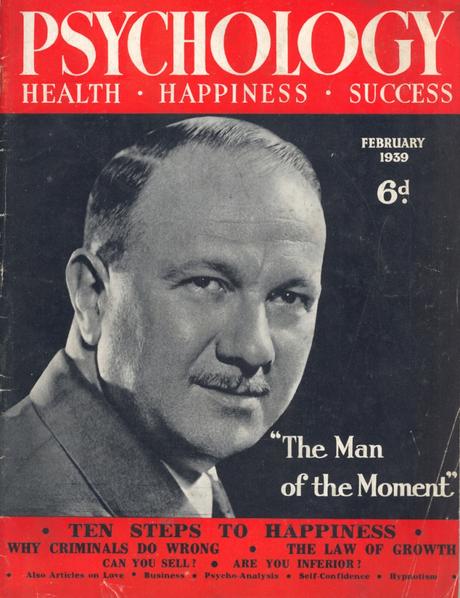

A July 1930 issue of Miller’s USA magazine and a February 1939 cover of a similar magazine that he helped found in Great Britain in 1937. Miller is shown on the cover.

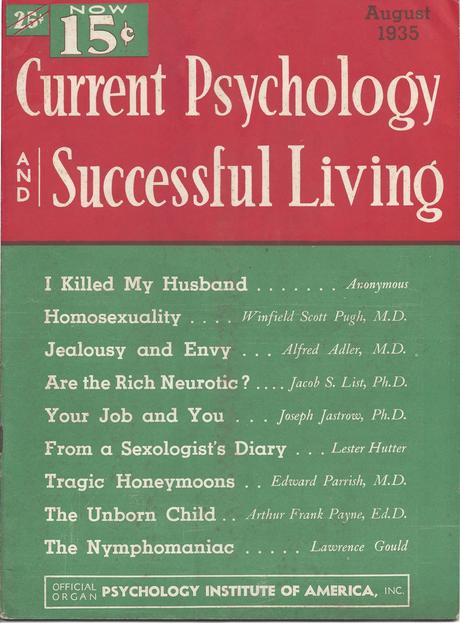

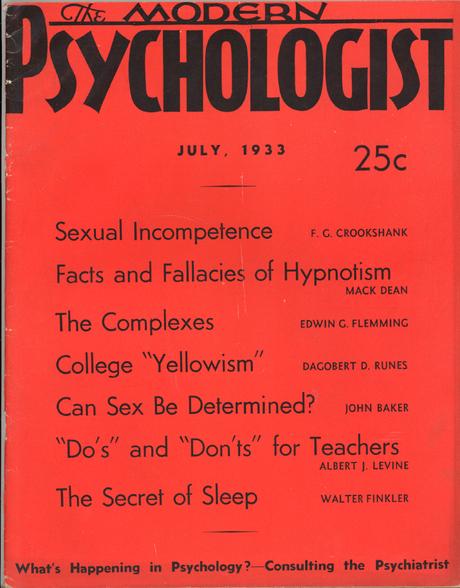

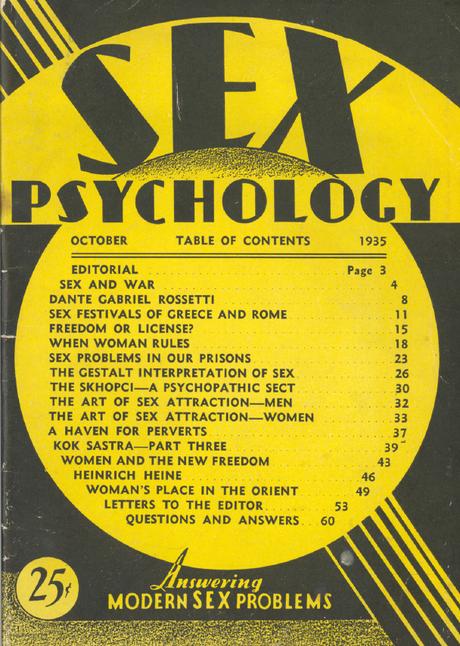

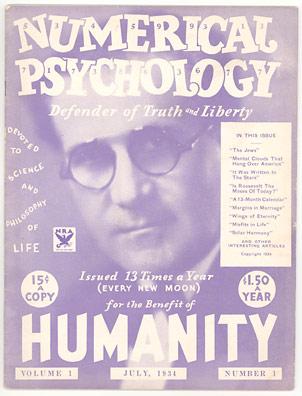

When the stock market crashed in 1929, the public euphoria of the 1920s gave way to the Great Depression that had profoundly disastrous consequences both economically and psychologically. Psychology received some negative press in the 1930s from writers who were especially critical of the field, noting that psychologists had plenty of advice to offer during the heady times of the 1920s, but now in times of trouble, they were conspicuously silent. One might assume that the public lost faith in psychology as well, and that the psychology magazines would disappear. Yet the message of psychology’s value for self improvement, for the betterment of one’s life, was evidently well engrained in the public’s psyche. These were times when psychology was needed more than ever. And even though two or three dollars might not be an insignificant sum for many Americans down on their luck, it was a small price to pay for a year’s subscription to a magazine that might put them on the road to economic and psychological recovery. At least two dozen new American magazines began publication in the 1930s with “psychology” in the title, for example, Current Psychology and Successful Living, Practical Psychology Monthly, Psychology and Inspiration, and Self-Help Psychology.

Four American popular psychology magazines that began publication in the 1930s

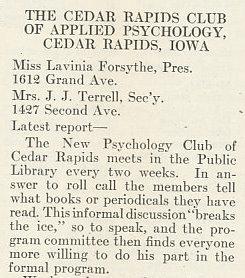

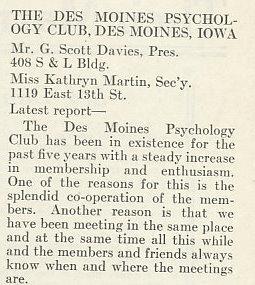

One of the tactics used by the popular psychology magazines was designed to increase circulation of the magazines and often to sell other products, typically books and pamphlets that were associated with the magazine. In the 1920s, psychology clubs emerged in cities all over America. In fact, there were some in existence in the previous decade, but in the 1920s their numbers expanded considerably. The magazines sought to establish ties with the various clubs. If all members of a club agreed to purchase subscriptions to a particular magazine, then the magazine would be sold at a discount to all members. Further, the magazine included a regular section that reported “news” from the psychology clubs, which gave visibility and publicity to the activities of the clubs while cementing the magazine–club relationship. Miller’s magazine was particularly successful in building such relationships. Some of the larger clubs met in some kind of meeting hall, but most were small in membership and typically met at someone’s house. Programs usually featured a lecture (rarely from a psychologist) and discussion, or discussion of a book or article. Miller was a great organizer of the clubs in America and often traveled to larger cities speaking at joint meetings or conventions of the clubs. Based on the entries in magazines, these clubs may have been composed equally of males and females in the 1920s, but by the 1940s, membership was heavily female.

Below are portions of two entries from Iowa psychology clubs that were published in Miller’s magazine in the 1920s. The nature of these clubs might be compared to modern book clubs where all members would read the same book or article and come together for a discussion, or hear a lecture on some psychological topic.

All of these images are taken from the magazines that comprise the Ludy T. Benjamin, Jr. Popular Psychology Magazine Collection which is housed at the Cummings Center for the History of Psychology. The collection contains more than 3,500 magazines from 150 different titles, ranging in date from 1844 to 2020. On the Cummings Center website, you can find the covers and tables of contents for 3,375 magazines that have been entered into the online database. These magazines represent a broad and rich tapestry of how psychology has been presented to the public, and have proved to be an important resource for projects for students and research for scholars.

Of course popular psychology magazines still exist today, most notably Psychology Today, which began publication in 1967, and Scientific American Mind, which started in 2004, a magazine that because of its affiliation with Scientific American, is predictably very scholarly. And you can find these popular psychology magazines in most countries around the world.