I had the pleasure of admitting a gentleman in his 70's who was transferred from a small, outside hospital for unstable angina (chest pain from heart disease) and required further workup.

Of note, his glucose was elevated at 290 mg/dL (16.1 mmol/L) on presentation to the emergency department, with no prior diagnosis of diabetes at the time of admission. When I started discussing his hyperglycemia, he recounted how he had been indulging on fine cuisine while vacationing in Italy the previous month and had since been settling back down to his usual routine.

On review of his old records, it was evident that he should have been classified as "pre-diabetes" for at least the past six years. Also, for at least the last eight years, his triglyceride/HDL ratio - considered the most powerful predictor of developing coronary artery disease in one study - had been over five, indicating that he was at a markedly increased risk. [Note: His LDL was in target range at 65 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L), and he had been taking a statin.]

In fact, he had required a coronary artery stent only seven months prior. In addition, he was being treated for congestive heart failure (CHF) and atrial fibrillation.

In addition to the known coronary artery disease and the new diagnosis of diabetes, there were a multitude of other clues to indicate that this gentleman was metabolically "broken": Hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), peripheral neuropathy, peripheral vascular disease, and erectile dysfunction. Even the diagnosis of acanthosis [nigricans] was made three years prior - a strong indicator of insulin resistance. Other problems in his record included varicose veins, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), and delayed healing of a skin wound. All of these problems can be part of the more encompassing syndrome of insulin resistance.

The morning after he was admitted to my service, he was taken to the cath lab where he underwent a cardiac catheterization. In short, he required a new stent for a 90% lesion of a different coronary artery from the one previously stented, which had been found to have no significant narrowing just seven months prior.

After returning to the medical floor and as soon as he was allowed to do so, he was walking around the halls, chomping at the bit to go home. When I arrived on the unit to meet with him again, I had to walk a couple of laps with him in order to talk with him before finally dragging him back into his room to examine him and discuss his discharge plan.

I gave him my usual presentation about the role of nutrition in diabetes and heart disease. He confirmed that he was under the impression (as he had been taught) that fat intake causes heart disease.

After destroying that myth, I explained the concept of insulin resistance and the rationale for a low-carb diet at reversing diabetes (and all the related metabolic disorders afflicting him). At one point, when I emphasized that the important step was to go low carb, he replied, "I'll go zero carb...you scared me!"

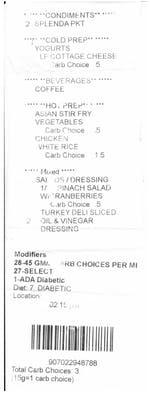

I had to step away for a while, then returned to his room to find that he had eaten his entire meal.

When I inquired as to why he ate the rice after he just heard my excellent argument against carbs, he said, "You pointed to the rice and frowned; you didn't tell me not to eat it."

"Huh", I replied, nodding my head and dropping my shoulders in defeat. At least he had ordered it before hearing my spiel, I thought, - I'll give him that. Then, pointing to the meal ticket on his tray, I asked, "Can I have this?"

"Sure," he replied. Then, after a slight pause, "You need to get a hobby."

A couple of months after my encounter with this gentleman, I again reviewed his chart to follow up on his health since I had last seen him. He had followed up with his primary physician and his cardiologist. Unsurprisingly, this cardiologist recommended a low fat, plant-based diet. Unfortunately, I do not know what he has actually been eating - because physicians just don't ask. I do know, however, based on my discussion with him, that he has no interest in a vegetarian diet.

Take aways

There are several take-away points from this patient's story that deserve mentioning as areas for improvement in health care, least of which being his closing reminder that I may spend too much time thinking about nutrition.

- There was an extensive trail of follow-up appointments and medication refills over a span of a few years under the care of both a primary care physician and a cardiologist, but there was no mention of dietary habits or intervention until he returned to his physician with the new diagnosis of diabetes that I just made. This omission is a perfect example of our current crisis of providing only "sick care" rather than "health care" - a whole lot of attention to pharmaceutical "band-aids" while ignoring the root cause.

- His physicians were so focused on his established diagnosis of coronary artery disease that they missed the underlying pathology - insulin resistance. There was no documentation of the diagnosis of prediabetes (aka impaired glucose tolerance) and the multitude of other markers of insulin Resistance as previously described. Here was a guy who would have taken action if he had known that he needed to do so. Perhaps educating him on a low-carb diet could have helped him avoid the diagnosis of diabetes and prevented the progression of his heart disease.

- The standard approach to this patient is very mechanical - put in a stent, adjust medications, and send home. Practice standards and "core measures" mandate the use of pharmacologic agents in the management of heart attacks, but fail to give any attention to lifestyle interventions. In a situation like this, however, it should be gross negligence not to educate this gentleman on the underlying problem of insulin resistance - the pervasive pathology driving his extensive list of medical diagnoses. Clearly, as I learned from reviewing his records, no one else was going to show him the "big picture".

- Despite being on an aggressive pharmaceutical regimen directed at his known heart disease and the traditional lifestyle advice (low-fat diet) imparted to him at previous hospitalizations, there was significant progression of coronary atherosclerosis compared to just seven months prior. Sadly, we keep doing the same things that don't work.

- It takes a lot to change behavior. Requiring another coronary artery stent and being diagnosed with diabetes certainly got his attention, but he needs to adopt major lifestyle changes to avoid further complications. As evidenced by his simplistic excuse for ignoring my advice (eating the rice), though, he needs guidance - clear, direct and consistent guidance - lest he continues to seek the short-term pleasure of eating rice when it's not in his best interest to do so.

Unfortunately, the shortcomings described above are far too common in health care, as there remain many barriers on many levels to optimal care. Imagine instead how things might be different for this gentleman, had someone recognized the warning signs of insulin resistance five+ years ago and advised appropriate, effective lifestyle interventions. Though I have now equipped him with the knowledge that he needs to succeed, he and many other individuals suffering from the same metabolic derangement from carbohydrate intolerance are more likely to achieve long-term success if their health care professionals encourage interventions that directly target the root cause rather than merely the complications.

Part 1:A day in the life of a low-carb doctor