In this follow-up post to last year's Slow Relating, two of my connection-focused selves come together to explore relating in more consensual, trauma-informed and plural ways. They reflect on how Dunbar's number can be helpful for structuring relationships, how we can attend to the balance between connection and protection, and what it means to adapt relationship containers in order to be as warm and open as possible.

If you haven't read one of my plural blog-posts before and aren't sure who these people are, feel free to check out my Plural Selves zine, and my previous post about plurality. But hopefully you don't need to get that part in order to find the relationship related content here useful.

Ara: Hey Tony, so good to get another chance to talk with you.Tony: Over a year since our last post together Ara. So much has happened since then, I can't even.

Ara: Seismic shifts out there and in here. How does it feel to come back to write with me after all of that?Tony: Vulnerable. We haven't written one of these plural conversation posts for a while. But there are a bunch of topics that we'd love to hash out together in this way - to get a better handle on them ourselves as much as anything.

Ara: So let's do it that way. Just talk together here on the page, and we can think later about whether - or how - we want to share this.Tony: I'm more cautious than last time we wrote huh? Less fastlove leap-before-you-look than I once was.

Ara: We've learnt a lot in the past year about what drives that way of relating haven't we?Tony: I thought I had a handle on it back then, but it was still kind of intellectual I guess: surface level stuff. Since then we've all learnt how to really feel the underlying feelings; to connect them back through the events of our lives. But that's for another blog post.

Ara: Perhaps it's enough to say for now that you are the part of us who is strongly motivated to connect with others, so much so that you've often prioritised that over other things.Tony: Like whether it's a safe-enough connection for the more vulnerable, frightened parts of ourselves, whether it's nourishing for everyone involved in the relationship, and what that connection means for the other relationships and projects in our life.

Tony: And you are the part of us who values slow moving and spaciousness: creating enough gaps and space around everything to really understand what's going on in ourselves and in others, in order to be able to act as wisely and compassionately as is possible for everyone right now.

Ara: Potentially a valuable alliance Tony: a part who is driven to connect with others, and a part who can remind us to go slowly and intentionally.Tony: It's hard to feel valuable sometimes, knowing how my old habitual way of relating has hurt us, and other people. And how it sneaks back in without me realising it and risks doing that again.

Ara: I know love. Not to get all 'It's a Wonderful Life' on you, but maybe it's helpful to imagine what we would be like without you: without that drive to connect.Tony: Hm, well I guess many of our other parts are mistrustful of other people, so if they weren't balanced by me we might get pretty withdrawn and isolated. Either that independent Max way of relating, not really letting anybody in or being vulnerable with other people. Or a more fear/anger driven Jonathan/Beastie mode where we tried to keep safe by staying away from others, or pushing them away from us.

Tony: Beautiful huh?

Tony: You make an excellent Clarence Ara.

Ara: Thankyou. So now you're feeling a little better, shall we get on to Dunbar's number?Tony: Right, that's what we were planning to write about. Let's do this.

Concentric Circles of Dunbar

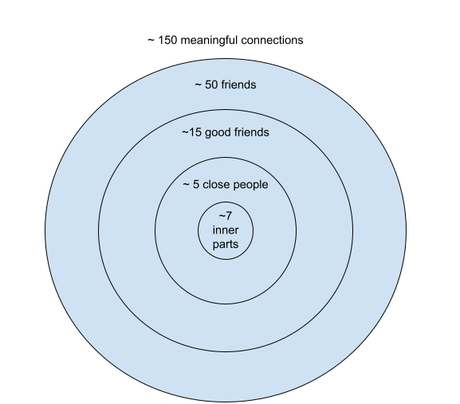

Ara: Do you want to say what Dunbar's number is first?Tony: Absolutely. It's a theory of this anthropologist, Robin Dunbar, who reckoned that the human brain can only handle around 150 people in our network of relationships. When we try to exceed that things tend to conflict and crumble. Nested within the 150 meaningful contacts that we can manage, there's a sense that we have an optimum number of around 5 close people, around 15 good friends, and around 50 people we might call friends. And beyond that we can maybe manage 500 acquaintances, and 1500 people in the world who we can recognise. People can read more about the idea here. Not everyone agrees with it, and it's unlikely that those numbers fit exactly for everyone. Culture, neurodiversity, trauma, how outgoing or introverted you are, and a bunch of other stuff probably comes into it too.

Ara: Right. It might be more useful for each person to reflect on whether a nested model works for them, how they might name each level of closeness, how many people they like to have in each level, and what defines that level, for them. It could be a very helpful thing to share with other people in our lives so that we can see how aligned we are in our ways of doing relationships, and where we might locate each other.Tony: Right. We've included something like this in a few of our books and zines. But applying Dunbar's number to it is new for us.

Ara: Shall we talk about how it works for us?Tony: Yep. So here's a diagram: how we find it useful to visualise it.

Ara: So anyone could draw something like these nested circles and then populate it with names: the people who would go into each level for them at the moment. It can be helpful to do this regularly. We notice how it shifts over time, and how it feels like people have a direction of travel inwards or outwards, for example.

Ara: So anyone could draw something like these nested circles and then populate it with names: the people who would go into each level for them at the moment. It can be helpful to do this regularly. We notice how it shifts over time, and how it feels like people have a direction of travel inwards or outwards, for example. Tony: We find it helpful to check the photos and contact lists on our phone and message apps to remind ourselves who we're in contact with, and think about where those relationships might go right now.

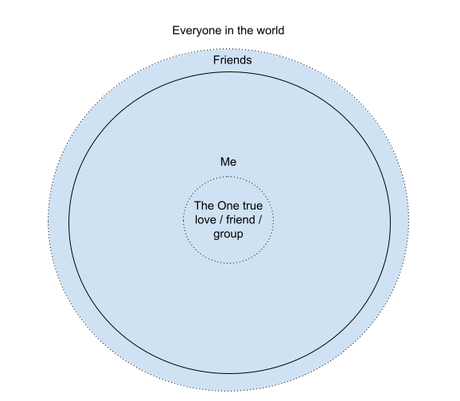

Ara: Shall we think about what defines the levels for us Tony?Tony: First I'd like to say something about what the model used to look like for us, mostly driven by my particular way of relating.

Ara: Sure thing.Culture, Trauma, and Dunbar

Tony: Here goes.

Ara: Oof. Do you want to explain that?

Ara: Oof. Do you want to explain that? Tony: Well thinking about Dunbar's number really helped me with this. I feel like I - and perhaps lots of people - pay very little attention to nourishing their 5, 15, and 50 relationships because they are so focused on The One and The Multitude. Like I think in the past I was highly focused on finding one, or perhaps two, really close people who would love me forever in the ways I've always dreamed of: partners and/or best friends for example. Sometimes that has also mapped onto the dream of finding a family or community where I got that kind of love. Those few people I valued more highly than myself, so I've put them in the centre of the diagram. Like I would put far more emphasis on their opinion of me than on my opinion of myself, and often try to shape myself to be what I thought they would most approve of. That's why I've put a dotted line between me and them, because I could get pretty enmeshed and entangled - losing myself in that relationship.

There's a big gap between the inner circle and friends because I would tend to only really be vulnerable, open and authentic with The Ones.

Then the other group I put a lot of emphasis on were people 'out there', hence the other dotted line on the outer circle. It didn't really matter whether somebody was a friend or a stranger, I would listen to their opinion of me equally, and I would want people I didn't know to validate me, and take it to heart if they attacked me or told me something was wrong with me.

Tony: It's not just me then?

Tony: So it makes sense that people become very focused on The One and The Multitude.

The problem is that culture and trauma channel all of that impulse for connection into a very small number of individual people who can never live up to all of the hopes and fears that we project onto them. And they also channel that impulse into a vast number of strangers who have built no kind of relationship with us, and will therefore find it easy to treat us in dehumanising ways - such as dismissing us as bad, wrong or unacceptable - as they've been encouraged to do by this highly toxic culture and by their own trauma.Tony: So we keep getting retraumatised in relationships, which repeats the earlier traumas that put us there and perpetuates a culture of cruelty where everyone is attacking and defending themselves 'out there' all of the time...

Ara: ...instead of focusing on the kinds of relationships that really could hold us and help us.Tony: It's tough Ara. Even though I totally buy this now, I still keep finding sneaky ways to turn somebody - or somebodies - in our life into that projection of hope. If only they would love me in that way, or tell me that I'm okay, then maybe I could believe it. And we still find ourselves instantly believing any negative thing that anybody says rather than running it through a filter of whether that person actually knows us.

Ara: My sense is that if we really knew anybody - like their whole history and what makes them tick - then we would find understanding and compassion for them.Tony: We call it the backstory effect. Like watch any of the medical or firefighter dramas that we've been binging during the pandemic and you'll see characters acting in outrageous ways that other characters attack them for. But we - the viewer - know their backstory, so we just feel for them deeply even as we're yelling 'no, don't do it!' at the screen.

Ara: One thing that Dunbar's numbers do for me is to get me thinking about whose opinions we value. In the first diagram we shared, our self (or in our case selves) are in the centre. We are always the person who knows us best. Tibetan Buddhism has a slogan 'of the two witnesses, hold the principal one', which means that whatever anybody else thinks of us, it's the view of the principle one - ourselves - which we need to prioritise.Tony: Mm, of course within this culture, and this experience of trauma, our views of ourselves can actually be pretty skewed.

Ara: So the emphasis is on building a deep friendship with yourself (or selves) in order that the principle one actually does become the most trustworthy. And around that, building trusting relationships with others such that we can know that what they say is likely to be coming from a place of care for us and care for themselves. In fact one of the things that would define those closest relationships for me would be people who deeply trust our own wisdom to know how we need to be and what we need to do in our life. They would also prioritise our own knowing of ourselves over their knowing of us, and would prefer us to do what felt right to us over what served them in some way.Tony: That's the kind of love we've written about before, which thinkers like bell hooks and Erich Fromm refer to.

Ara: Nice to see you've been listening to our more philosophical parts Trouble *grin*Dunbar and slow relating

Tony: Okay so how does Dunbar's number relate to the kind of slow building of relationships which we covered in our last post Ara?

Ara: What do you think?Tony: Always turning the question around. Alright, well it makes me think that nowadays I would want somebody to hang out in the 150 for a while before moving into the 50, and then there for a while before the 15, and definitely there for a good while before moving into the 5.

Ara: Not so much what we used to do huh?Tony: We... well I... used to move people right into the 5 on the basis of one connected conversation, or an erotic or romantic attraction. Like more than once I said 'I love you' after a few weeks of messaging with someone, or moved in with them a few weeks or months into a relationship.

Ara: So we now think of connecting with people erotically, cohabiting, having everyday contact, naming 'love', and developing a close creative collaboration, as all things we'd only want to do with folks in the 5 or 15. Although of course for other people the kinds of connection that are specific to those inner levels may be different. We would want that sense of having gradually developed trust and closeness with a person - probably over a number of years - before they were at that level.Tony: Right, those are the things that spook our 'fraidy parts: sudden declarations of love, crush, or friendship, or people slipping into expectations of regular contact, physical touch, or requesting crisis support, without having developed that trust over time, and having an explicit consent conversation.

Ara: Our 'fraidy parts', is that what we're calling them now?Tony: Not in hearing distance no.

Ara: Heh. It has been very useful though, to understand that we have - in us - parts who are driven by the fear of annihilation by others and the hope of safety, and parts - like you - who are driven by the fear of abandonment by others and the hope of belonging. And those parts can often feel in conflict as you prioritise connection over protection and they do the opposite. We'll come back to that shortly. I'm also thinking about how this model opens up the possibility for what we might call more intentional - or conscious - relating. Instead of people assuming what makes a partnership, a close relationship, or a friendship, for example, this enables there to be communication about what these things mean to each person, and whether there's a good fit between us in our understandings and expectations. It feels important that nobody is assumed to be in a specific place in our life due to something like being part of the same community or family, having erotic or romantic attraction, or having known each other a long time ago. The important questions are more like: 'is this relationship mutually nourishing for us both?' and 'at what level of connection is it most mutually nourishing?'Defining Dunbar's levels

Tony: Can I say what defines each level of closeness for us? It's still a work in progress but we're finding it useful to articulate - to ourselves and others - what makes something a friendship, or a close relationship.

Ara: Go ahead.Tony: I'm going to try to make a list. These seem to be the defining features of friendship for us:

- We're invested in supporting each other in our projects and in our other important relationships.

- We share a commitment to being as kind and caring as possible with each other, assuming that we're doing our best.

- We can each bring all of ourselves to the relationship, including our vulnerable parts (more explicitly in a plural way with our closest people).

- We value each other's freedom over what they might be for us. For example we'd rather they were in consent than overriding their consent in order to be in contact with us in some way we might like.

- We each trust the other person to know themselves best. When we don't understand something that they are feeling or doing we assume that it does make sense.

- We each respect where the other person is on their journey - and their sense of what their path needs to be - rather than believing they should be in a different place or follow a different path.

- We share a commitment to doing The Work with ourselves, and seeing that as a lifelong journey (that might manifest in engaging in ongoing spiritual/therapeutic practice, for example, and continuing to cultivate a supportive network of people).

- We're up for being transparent about the relationship with each other and with our other good friends, so that problems don't get hidden, and we have other people to support us through any tough times.

- We try to notice when we're reactive and refrain from communicating when we're in that place. We try to acknowledge the impact it has when either of us does communicate from a reactive place, as well as having a lot of kindness for where that comes from in terms of trauma, and for how incredibly painful it can be when we realise we've hurt someone else with our reactive habits.

- We're up for the relationship changing and shifting Dunbar position over time depending on what's working for us (if it's not working for everybody, it's not working for anybody).

I guess that people in the category of 'friend' would tick most of these, and 'close people' would tick all - or nearly all - of them.

Ara: Right. Maybe it's the case that the closer in somebody is on the diagram, the more aligned we are in terms of these values and ways of relating. And we're interested in spending the most time - and having the most overlapping lives - with those who are most aligned. In those cases we're most engaged in supporting each others' projects, and doing ongoing practices to nurture the relationship.Tony: With the 150 - or the 50 - it may be more that we have shared interests - although with us this geeky stuff about how we relate with ourselves, each other, and the world, is always a pretty important one. But the closer in relationships need to have more of a shared way of understanding and doing relationships, for us.

Connection and protection

Ara: I'm thinking that there's two different components here, aren't there? It's about both connection and protection.Tony: Right, the closer relationships are the ones which feel more connected, and so it feels most enjoyable and meaningful to hang out there, like we can be ourselves and belong. And those relationships are also the ones where it feels we've built up enough trust to feel safe enough there. We feel protected enough that we don't have to worry that the person may suddenly lash out at us, or try to constrain us, for example.

Tony: I feel like I used to prioritise connection way over protection. If it felt like a good connection with somebody I would ignore or accept it if they hurt us or tried to restrict us. Almost like I thought that was the price of entry for connection. That's the big shift I'm trying to make now: to value myself enough to believe that I can have both connection and protection.

Ara: Meanwhile our 'fraidy parts' work on taking the risk of connection where there is evidence that the relationship can be protective enough.Tony: And the part of us who is best at clear-seeing and boundaries helps us to discern which relationships those are, and to articulate the level of relating we're up for with various people.

Articulating that does risk us feeling like we're letting someone down if we can't give them what they want. That's something which often brings up a lot of fear (that they will overstep our boundaries) and shame (that we should be what they want us to be regardless of what we want). It also risks us feeling rejected if the person doesn't want the level of closeness with us that we think we'd like with them.

Ara: Back to annihilation and abandonment. Again this is why slowly deepening closeness feels better to us, because we can get a really good embodied feel for the relationship before getting closer, as well as having explicit consent conversations about what getting closer means for us, and for them.Tony: Going back to my old way of relating, with this model it makes sense to invest the most time and energy in the closest-in relationships, ensuring that we're being relatively even between all of the 5, and all of the 15, rather than focusing on just one or two of them. We can usefully ask ourselves what relationships at this level need, in order to nurture them, and check if we're continuing to do that. That's pretty different to the wider cultural model where you take good existing relationships for granted and focus all your time, energy and specialness on the shiny, new ones.

Ara: Which we would now see as at the outermost level. I'm also thinking about something we spoke about last time Tony, what one of our friends calls the hokey cokey.The hokey cokey

Ara: The hokey cokey is the sense that it's okay - vital even - for relationships to get closer and more spacious over time: to move up and down the levels in our model.Tony: In out, in out, shake it all about!

Ara: And that's something that we - and others I'm sure - struggle with. That's down to a combination of culture and trauma too I suspect.Tony: Right. This feels exciting, I haven't really thought this through before.

Tony: So the cultural piece is that we tend to equate closer in with better. Like those in our innermost circle have won the game of MJ or something! Like somehow it's winning for them to be so close in, and someone it's winning for us to have them there. So it'd be losing for them to move further away.

Tony: And the trauma piece relates to abandonment - my stuff - like someone moving from closer in to further away can easily be read as rejection of me, triggering that sense that there's something wrong with me, people always leave me, blahblahblah.

Ara: Which in turn triggers your defense of self-deprecating humour perhaps?Tony: Damn you.

Ara: I see you Tony.Tony: *grin* alright. So what's the alternative to closer in equals better, and moving away is bad?

Ara: I think it's something we've recently explored with a couple of friends where we've explained that deliberately keeping the relationship spacious and going slow is a sign of how deeply we value it, not of it being of lesser value. Better to keep a relationship in the 50, or the 15, for long enough that we can mutually evaluate whether it feels good there. And by then we would have become familiar and practiced enough with each other to explore whether moving closer might be something that would work well for us both, and what that would look like if we did. We would also feel able to discuss how we'd enable each person to step back again if we tried it - got more information - and realised it wasn't working for us.Tony: It's about fit really huh? Where on this model is the best fit for this person - with us - at this point in time? And that gets us to that 'warm and open' question we've been asking a lot lately.

Maximising warmth and openness

Ara: I'm finding that so helpful. The question we ask ourselves goes something like 'what container does this relationship need in order for us to be as warm and open as possible within it?' In that sense the relationship 'goal' shifts from 'as close in as possible' to 'wherever we need to be to maximise warmth and openness'.Tony: That feels a bit like that consent shift from the goal of a date being sex (whether or not consent happens), to the goal of a date being mutual consent (whether or not an sex happens).

Tony: I'm also thinking that the capacity to hokey cokey with people is potentially less likely to retraumatise everyone. The culturally normative model tends to have people going suddenly from the inner circles to the outer limits if there's any kind of conflict or rupture. That's often felt as a total abandonment - and annihilation I guess because we can take it as evidence that there must be something terribly wrong with us. It's so much more helpful - and less retraumatising - if each relationship can become more close or more spacious - if it can expand and contract in that way over time.

Ara: And we're up against a lot in trying to do that. Like you say culture and trauma, because there's a lot of external and internal pressure to completely sever a relationship when there's a rupture, to either label the other person bad and reject them entirely, or to label ourselves bad and be so swamped in shame that we can't handle their presence. And trauma makes us more likely to experience increased spaciousness in a relationship as abandonment, and either to push the person away entirely because we're so hurt, or to try to cling on in a way that makes them distance themselves more.Tony: I'm sure that nobody round here would ever do any of those things Ara.

Ara: *chuckles* like I said we're up against a lot with that interwoven culture and trauma piece. All of us are.Tony: Is there anything else to say about the hokey cokey?

Moving up and down the levels

Ara: I suppose I'm wondering whether - in addition to putting more time and energy into the closer-in relationships - we might also put particular time and energy into relationships when they are moving up or down a level, to ensure that that is as caring and consensual a process as possible.Tony: Mm I notice that relationships in those kinds of places, perhaps with a question mark around whether they might need to move closer in, or further away, feel kind of edgy. There's an impulse in me to put too much time and energy into them too - like in a rush to figure out where they should be and pin them down.

Ara: Mm good point, it's about the quality of the time and energy more than the amount of it perhaps. I like the idea that we have an honest sense - at any point in time - about what those 'on the line' relationships are for us. And we keep slowly, gently, exploring in ourselves what's going on there, until we reach some clarity around what the issues are for us, in a way that feels possible to communicate with the other person.Tony: It's another way that I want to leap huh? Leaping to clarifying it, rather than staying with the uncertainty for long enough to get clear.

Ara: Again a pretty common struggle. But patience is important here, and getting more information. Like contact with that person - or space from them - will help us to get clearer on what's going on here that might mean we need to move closer together, or further apart.Tony: An example for me would be that it can take some time to tease out whether the desire for more closeness is coming from my Deep Yearning of the Soul (™) or whether it's coming from a recognition that the relationship meets a lot of those criteria we mentioned and might work well for both of us at a closer level.

Ara: And for our 'fraidy parts' the question might be more whether the desire to move further apart comes from a clear sense that the level of closeness isn't working for us, or more from old stuff that's been triggered in us, which we might find a way to communicate with the other person.Tony: Right, we have a few examples lately where those parts of us have felt that fear, taken the risk of naming what felt scary to them, and the person has responded really well, leaving us feeling way more warm and open towards them.

Returning to our sides of the street

Ara: Again trauma is such a big part of all of this. One of our close people has a great analogy for those periods where a relationship requires more spaciousness or stepping back. They say that a relationship is like walking down a street: we can both be on separate sides of the street, or we can be in the middle of the street together. When there are ruptures, or when we realise that we've become too entangled and lost ourselves, or the other person has, or we both have: those might be the moments to move from the middle of the street to the separate sides again, at least for a while.Tony: Right. From opposite sides we can find our individual path again if we've lost it a bit. We can also look over and get a better sense of them, and their path. It might be that we've forgotten that in wanting them to be something for us, or in wanting them to be on the same path with us for some reason.

In my mind it looks more like two people finding different paths up a hill than two sides of the street.

Ara: Nice. And it can be great to be alongside each other on the same path for a while, but we can also be alongside each other on different paths when... I don't know...Tony: ...when one of us is fitter than the other, or more scared of heights. And sometimes their path may take them onto a different hill and that's okay too. Are we stretching this metaphor to breaking point yet?

Tony: Anyway it's about recognising that both closeness and spaciousness are valuable in relationships, and that the important question is what Dunbar level this relationship needs to be at in order for us to be as warm and open as possible.

Ara: And that it's okay - in fact vital - to hold that question open for a while, when relationships are in an uncertain place, rather than leaping to try to locate them again, or putting them under pressure to be in a certain place.Nurturing inner and outer relationships

Tony: Okay onto the last bit we wanted to mention. In our Dunbar model our very innermost level isn't a relationship with another person - or people - any more, it's our relationship with ourselves.

Tony: It might seem obvious to put ourselves in the middle but, as I said before, for much of our life I don't think that we did - not really. If you have that sense that you have to shape yourself in order to be loved by others, or to belong, then you're putting them at the centre, not you.

Tony: So just to be provocative, isn't putting yourself at the centre valuing yourself over others?

Ara: Just to be provocative huh Trouble? It's actually a really important question, and again I think it comes down to the quality of it. There's a way of centring yourself that is really bad for you, and for others. In that mode we see everybody else through the lens of what they are for us, and we take everything that others do and say very personally.Tony: Familiar. That's such a painful place to be. Like other people are hurting us all the time because they don't want to be as close as we do, or because they want to be closer than we do. And when people come at us with their stuff we internalise it and use it to beat ourselves up with. In that mode of relating other people feel very dangerous, and yet we also can't seem to stop ourselves from churning over all the relationships we've struggled with in the past - and are struggling with now. Perhaps we find ourselves obsessing over this person, while trying to eradicate that person from our mind. And none of it works and we feel worse and worse.

Ara: You're so good at describing these things Tony.Tony: I surprise myself sometimes. I wasn't expecting to go there. In terms of our inner system that's when the whole thing seems stuck. It's me, Max, Jonathan, and Beastie all struggling simultaneously. I try to grab onto people who might prove I'm loveable and give us connection. Max tries to do a bunch of stuff to make other people respect and approve of her. Jonathan recalls every criticism everyone's ever made of us and tries to predict what we might 'get wrong' next, wishing we could hide away from everyone. And Beastie judges everything we're doing, and everyone out there. And we feel disconnected from ourselves and from everyone else.

Ara: Putting ourselves at the centre of Dunbar's model is about something very different to that, for me. I'm thinking about a quote we heard from Pema recently, in her new audio 'Journey to Fulfillment'. Ara: I'm so grateful to her.Tony: Always with Pema!

Ara: Agreed. She says: 'It's that attitude about ourselves that actually we are worthy and we are basically decent and good people, and we could begin in our life to get that sense of fundamental okayness, fundamental wholeness, completeness. And the result of that would be very beneficial. That's the most benefit that you could possibly give to another person.'Tony: Me too. I don't know how we'd have got through this last couple of years without her.

Ara: I know. We've been far from that for much of our life, and lately experienced being about as far from it as it's possible to get.Tony: Fundamental okayness sounds so good.

Tony: Almost like we had to go further away from it to get closer to it. So much paradox.

Ara: It's such a strange one isn't it, like it's both far too much 'all about me' and far too much 'all about them'.Tony: Right, because that painful kind of centring is not really about putting yourself at the heart is it? Because you're actually super focused on other people: still trying to get their approval, and still really scared of their disapproval.

Ara: Very clever!Tony: Instead of being all about love. See what I did there?

Ara: Anyway I think what we're endeavouring to do here - in our life at the moment - is to find that sense of okayness in ourselves. And part of this whole Dunbar's model thing is about that too.Tony: I try.

Ara: Because it's about learning which kinds of relationships - with which people - help to nourish that sense of okayness in us, and which don't, and being open about that. And it's about a desire to be that for others too: noticing where we're not that person for somebody - at least not at the moment - even if we, or they, might want us to be. And being up for retreating in those cases.Tony: Go on.

Plurality and okayness

Ara: A key way in which we're learning to feel more okay, more complete even, is making an explicit task of befriending each part of us - when they're struggling and when they're doing okay - letting them know that they are welcome no matter what, loved no matter what.Tony: Yeah. I see. And for us plurality is a huge part of how we're doing that.

Ara: I might suggest 28 rather than 21 Tony.Tony: So a lot of time and energy goes to that, because 7 parts means 21 different relationships to nurture. It's not enough to just have one part loving all of us, we all have to love each other.

Ara: Each part has a relationship with themselves too.Tony: How come?

Ara: All four of you - Max, Jonathan, you and Beastie - hold that sense that you 'ruin things' for the rest of us, that you are the part that isn't really okay.Tony: Ah shit I missed that. And that's the hardest one too. I actually feel all 6 of you loving me now - although you certainly demonstrate it in different ways! But I still struggle to love myself: to feel that I'm okay.

And when we do that we are far less likely to internalise other people's attacks and abandonments, because we'll know where they come from: that sense in them that they are not okay, or that parts of them are not okay.Tony: A work in progress then.

Ara: It helps me to weave together the Buddhist writing we read which emphasises the importance of inner work in solitude, and the trauma literature which suggests that healing can only be done in relationship.Tony: This model reminds me of something that we got from Pete Walker's book. He says that trauma healing requires 'reparenting ourselves' and 'reparenting by committee'. We're nurturing our inner relationships in order to reparent ourselves - like you and James caring for and protecting all of us, and all of us being able to grow up because of that. But we're also nurturing these close relationships and friendships as a kind of committee of people out there who are invested in supporting us, in reflecting back our okay-ness, maybe even when we don't think we're okay.

Ara: It so often is.Tony: To quote Forrest Gump, 'I think maybe it's both.'

Limiting the numbers, limiting ourselves?

Ara: Well I think Rumi's poem partially answers your question Tony, because it's actually about welcoming every part of yourself in, not other people. Again it takes us back to the sense that only in so far as you can befriend every part of yourself can you really befriend others. I don't think that it helps other people if we fling open the door to everyone and then find that we can't be alongside them without freaking out.Tony: Okay so provocative question number 2, how does this Dunbar model of only relating in a small 'village' of relationships relate to the spiritual aim to be of benefit to all beings. Like that Rumi guest house poem: aren't we meant to be striving to welcome everyone? And in limiting ourselves to relationships that feel good to us aren't we just creating an echo chamber of people who'll tell us we're awesome, so we'll never have to address our limitations?

Tony: It's window of tolerance stuff isn't it? Knowing our limits. And the concentric circles are about that too. What level of relationship we can be in with people and stay grounded - so we're able to be warm and open? We're not of much benefit to ourselves or others when we're going into an overwhelmed or retraumatised state on the regular.

Ara: It's a similar point I think, that repeatedly plunging ourselves into overwhelm by engaging with people, opinions, and ways of behaviour that are very jarring to us doesn't actually help us to expand our window of tolerance, or our horizons. I do think it's very important that we learn to be alongside people who are different to ourselves - and have different views - in a world where The practices which work for bringing people together who have very different views - or who are in conflict - involve nurturing trusting relationships between them which are held and supported by those around them, and helping them foster understanding and compassion for each other. Only at that point can people really hear those differences without trying to make the other person bad, or rejecting them. polarisationAra: Right! Say more. and '' thinking is such a problem. But from what I've read from social justice and from various spiritual traditions, the only way to do that which seems to work is in relation. Ara: Such a good way of putting it. So at the moment we're building one group of people in our lives to support each other in being ethical and accountable in our work. Recognising that this would inevitably involve vulnerable conversations about the times we've messed up, the group is working to slowly develop trust and deep knowing of each other, so when something does come up we'll understand how it is hitting the person concerned, and know how best to support them through it.What about the echo chamber question?

Ara: In these examples we're explicitly attending to protection in order to allow more honest and vulnerable connection (both/and), rather than protecting ourselves by avoiding connection, or moving towards connection with little thought to protection. And we certainly notice that in relationships where we've already done this, conversations that might feel very hard elsewhere can feel relatively easy.Tony: I'm thinking that again it comes back to seeing connection and protection as a both/and rather than an either/or.

Ara: Mm there's something about similarity and difference here too isn't there. Our old ways of relating required us to believe that we were very similar to partners in all kinds of ways, and any difference was felt as threatening. Whereas this way assumes people are inevitably both different and similar, and aims for an approach where we can meet each other well in both. Like Audre Lorde says, 'It is not our differences that divide us. It is our inability to recognize, accept, and celebrate those differences'.Tony: The 'echo chamber' idea stems from the assumption that if relationships are protected (safe enough) they won't be connected (honest enough). That's the same idea that we can only get connection or protection, never both. If we have real connections with people they'll end up being too dangerous, and if we have safe enough relationships they won't be real.

Ara: 8000 words probably means time to wrap up Tony!But what we're trying to cultivate are relationships where the safety comes from the level of trust and deep knowing of each other that we've built, so it's the connection that gives us protection. And, feeling that level of protection, we can afford to risk greater connection: like telling somebody when we are struggling, or feeling a tricky dynamic come up between us.

Ara: I think that it does get us closer to safer, more connected, relationships. And, at the same time, you're wise to be wary, because once we start seeing it as the one true perfect model of relating that will give us all we ever dreamed of, we'll quickly learn that it isn't!Tony: That's a great example. We're also thinking about slow moving towards staying - and potentially living - with various friends - and their people - for periods of time post-lockdowns. There's a question of how we nurture safe-enough conditions to do that, again probably with gradual shorter stays - and/or in-advance conversations - so we can be connected enough when we are there, rather than feeling we have to go back to hiding parts of ourselves, or they do.

Tony: Absolutely, like recognising the places where we rub up against each other, or pin our hopes on each other non-consensually, or where our history together throws up certain dynamics. In those relationships it seems easier to spot, and name, those things, as well as being alongside each other in addressing the things that scare us, not hiding away from those things in a mutually reinforcing echo chamber about how great we are compared to everyone else.

Ara: Paradoxically dropping the hope/fear approach to relationships may give us more of the connection we hope for and less of the risks that we fear. It certainly makes it more possible to navigate when our hopes and fears crop up.Conclusions

Ara: I think I'd just emphasise the importance of being where you are with relationships, not trying to be 'further along' than you are. When we've tried to be somehow 'more' for people than we're capable of, that's when we've wound up pushing - or even retraumatising - ourselves in ways that aren't actually helpful for anyone. It takes courage to be that honest with ourselves and to recognise our limits. Offering what we really can, at each level of relating, is far better for everyone than trying to offer more than we can, or to bring people into a closer level when we aren't ready for that, or don't want it. Interestingly we've found with Max that a similar model applies to work. We can create Dunbar's rings of our various projects to consider where we want to invest our time and energy there, rather than - for example - putting most of our time into projects that don't nourish us, or believing we have to focus entirely on 'one true project'.Tony: Mm, I'm left with a concern that it's still so easy to 'pin' my yearning for protection and/or connection 'out there'. Even with this model there can be a hope that it might finally provide us with relationships that are completely safe, and where we totally belong.

Ara: It's been good talking with you again Tony.Tony: I've done this so many times, letting go of an old partner in the hope that a new partner will be everything, swearing off monogamy in the hope that polyamory will meet all our needs, swearing off fastlove in the hope that slow relating will do it for us.

It's realising that no other person - or people or relationship style - will ever make us entirely safe or give us total belonging. And, at the same time, it is worth working towards relationships which are safe-enough and connected enough.

Tony: Anything else to say?

Tony: I'll let you and her get into that one someday.

Tony: Right back atcha Ara.

Patreon link: If you enjoyed this please feel free to support my free writing on Patreon.

Plural tag: This post was by Tony and Ara.