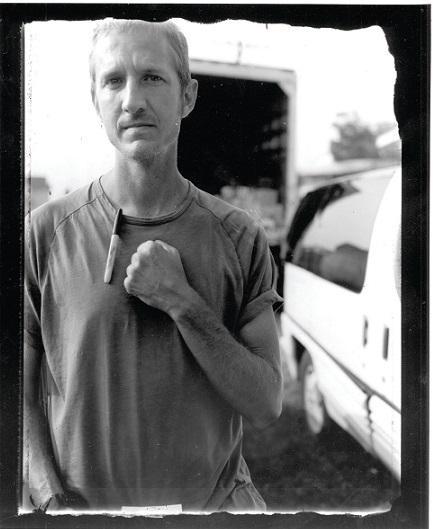

scott crow

by Kristian Williams / Toward Freedom

Brandon Darby has been notorious in anarchist circles for a decade — first as a wing-nut, a macho bully, and a womanizer; then as an informant and agent provocateur. He started out as a hippie, became a pseudo-militant leftist, and is now a pundit on conservative blogs. He has been credited with helping to found Common Ground Relief in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, and has been accused of nearly destroying the same organization to satisfy his own ego — or at the behest of the FBI. Following the 2008 Republican National Convention, he was the key witness in the prosecution of Brad Crowder and David McKay, young men charged with making firebombs. Their case revealed that Darby had been on the government’s payroll for years, and the two men point to his influence as the decisive factor leading them to consider arson.

scott crow is one of the few people who saw this entire series of transformations unfold up close. crow was a friend of Darby’s, one of the founders of Common Ground, and initially one of Darby’s most public defenders. He’s now one of his most vocal critics.

I met up with scott at the Anarchist Black Cross conference, held in an old Christian summer camp in rural Colorado. In our wide-ranging interview, he told me the story of his friendship with Darby, and its demise. He talked about Darby’s entrance into activism, his long history of troublesome behavior, and the movement failures that granted him such prominence and allowed him to work so much havoc.

The story he tells is not that of a hero turned traitor, but — more disconcerting, I think — that of a deeply damaged individual driven less by political principle than by paranoid/romantic fantasies and a desire for personal glory.

Beginnings

Kristian Williams: I’m going to ask you about your experience with Brandon Darby. The more you can talk about things that you witnessed directly, and things that you know firsthand, the stronger it’s going to be.

scott crow: Okay.

KW: How did you first meet? And what were your first impressions of him?

sc: I was introduced to Brandon in 2002, by a good friend of mine, Tracey Hayes, who I’d worked with on numerous political direct actions. She was dating him. He was an intense, late-twenty’s, good-looking guy; a weed-smoking, guitar-playing, sandal-wearing hippie hanging out in Zilker Park, in Austin. He wasn’t that politicized yet, but kind of angry and intense under the surface.

KW: You and he got to know each other because you were friends with her?

sc: Yes. At the time she was a marijuana legalization advocate. They visited me to find out how they could do a climbing banner action without being arrested beforehand. He played this really quiet, very unassuming person at first, and then as you get to know him he reveals his paranoia more.

Then, as the political arc goes, the anti-war movement broke out with all these mass demonstrations in early 2003. In one demonstration, an anti-war rally in Austin, some friends of mine had organized a lockdown circle of about thirty people, in the middle of the street for probably about three hours. Just barricaded the whole thing, stopped it with thousands of people around.

We were there together, with Tracey, and my partner, Ann. Brandon noticed that there were some possible undercover cops at this coffee shop he went in. He came back out declaring, ‘I think these guys are cops.’ I went in and confirmed it. They were typical type of narcotic undercovers, seven or eight, all beefy dudes with Lynyrd Skynyrd and tie-dyed t-shirts — so they thought they blended in with us. They’re all at a table together. I suggested, ‘We should photograph them; then publish their photos online, so that everybody knows that these people are undercovers.’

The lockdown is breaking up and a march starts to the center of Austin. Brandon grabbed a little camera at the convenience store and started to take their pictures on the way. While he’s doing this, he starts getting aggro with each of them, getting in their faces. You know, they’re in different places. Each one of them told him, ‘Stop fucking with me, or you’re going to get in trouble.’ That’s when one of them flashed a badge to confirm it was sheriff’s department. He kept on anyway. I stopped walking with him. I didn’t want to have anything to do with it. Just take the pics, publish the photos and be done with it! But he kept it up until the undercovers focused on him and more police were brought to our immediate area.

Finally, after five hours, I leave this demonstration. It went on for nine or ten hours; but I left. There was another lockdown on a bridge near downtown. He wasn’t on it, but was close by when he finally got swept up by the undercover cops.

This is where the story gets tricky, because I am not present anymore, but he’s calling me on the phone as they surround him. This starts a pattern for the next few years where he calls me regularly, all the time. He says ‘what should I do?’— in a panic. Eventually, they take him and they put him in a van, and they told him that they’re going to fuckin’ beat the shit out of him or something. This is what he says.

Of course he loses the camera and pictures.

KW: Does he tell you this on the phone at the time?

sc: Yes, while he was held in the back of the van. He’s saying, ‘They just threatened me.’ I was mad at him for dragging me into it.

He never got charged. This is where it gets gray. Nobody knows what happened. The legal team never went to go give him support or anything. Around the same time he was picked up, a bunch of people got arrested, about 9:30 or ten o’clock at night. The cops wanted to open this bridge up and started arresting people. He says he was arrested, but there is no record of it.

At the time I said, ‘Fuck this guy, he only cares about himself.’ He’s a wingnut and he endangered people around him. He doesn’t want to listen to anything and is dangerous in these situations.

KW: After that, did he try to get more involved politically?

sc: A couple of weeks later, some of the same activists who did the lockdown wanted to build tripods to block an Exxon gas station and roadway. I consulted with them to construct the tripods and figure out how to strategically do all these things. They lead the action; I just consulted with them.

Brandon kept wanting to be in the action. He called repeatedly, but I kept putting him off. After what happened before, there was no way. He badgered me. You have to understand, this guy would not just take no! He would relentlessly call or come by my house the whole time I knew him.

So I finally gave in and said, ‘Look. You can have this low-level role where all you do is drive up, drop these barrels in the road, then leave. Then you stand over on the other side with me and you watch.’ I was going to be on-site communicating about safety issues, but not in the action.

We watched from across the road as the cops arrived. They immediately knock these women out of the tripods. It was pretty dramatic. Then Brandon runs across six lanes of traffic, screaming and pointing his fingers at the cops escalating the situation. I said to myself, that’s it! That was when I was definitely not ever working with this guy again. He was too erratic, too unhinged. He made the action about himself versus the cops again. They arrested everybody immediately.

Before I get out of chronological time, it’s important to understand that Brandon didn’t hang out in the Austin anarchist, or the activist, scene very much. When we were doing anti-war spokes-councils or planning, he would come to the meetings sometimes — but barely, and he was often late. He didn’t participate as much stand on the edge and smoke cigarettes. He wasn’t part of any groups or an affinity group. He was around due to his relationships with a few of us.

A short time later, Tracey broke up with him. They had a problematic relationship. He was very paranoid and jealous, it turned out. He was reading her e-mails, going through her phone numbers. She asked my partner and me to not hang out with him. So we didn’t. We didn’t see him for months.

Fantasies

KW: Did this paranoia show up in other ways?

sc: During all of this, from 2002 to 2004, he is constantly talking to me in private about armed action. He didn’t own a gun when we met—and then he started buying guns. When he got a little bit politicized, he wanted to go into a place like Wal-Mart and shoot everything up, and then take himself out. To him that was a revolutionary act. He had this double-narrative in his head that he started to develop early, which was: ‘I’m going to go to prison, or I’m going to die.’ To him both of those were glorious options.

His story was nuts. He wanted to go postal. I said, ‘If you go and shoot up all the people at Wal-Mart, they still stay in business, but you’ve basically killed a bunch of innocent people.’ He eventually changed to wanting to go after the executives. He was vociferous about stupid ideas like this. He wasn’t trying to get me involved in it. He would debate me about it. And I’d say, ‘I’m not going to argue with you about it. This is the stupidest-ass shit I’ve ever heard! Stop fucking talking about it.’ It came up more than I was comfortable with.

You know, other people have approached me in the past about doing covert actions of different types, including property destruction. Usually, I try to talk to them strategically: Who’s affected by this? What’s the end goal? And then I turned him on to ideas of the ELF (Earth Liberation Front) and the ALF (Animal Liberation Front) and the tactics being used, sabotage and monkey-wrenching. He started to talk about it in that language. Again, not trying to engage me, but still talking annoyingly and very forcefully about this.

Then he got really fascinated with the Black Panther Party. He became obsessed with the armed aspect, and the Central Committee — being a leader and in control — not the community programs or organizing. He was always at odds with me and with anarchist politics.

KW: Along with his going postal and taking himself out, and so forth, there was a story about going to prison?

sc: He had this other narrative. It was actually quite humorous. He would start telling this elaborate story, ‘Yeah man, I’m gonna go to prison, and I’m gonna need somebody on the outside.’

He was sleeping with a lot of women, you have to understand, all through this. That’s the way he was. Not in activist communities, but around. He goes to places to meet them and sleeps with them, that was his main M.O. And while doing that, he wants to have what he called his “revolutionary baby” with some woman. He wants to get her pregnant, but he doesn’t want to take care of the baby. The community is going to take care of the baby because he’s going to be in prison for revolutionary acts.

The second part of the prison narrative is that he was training in cage fighting, so that when he went to prison and somebody tried to “ass-rape him” (his words), that he could fuckin’ pull their eyeballs out and just beat them to death.

He was socially awkward. So, there’d be a group of people around, just talking about things, or whatever, and he’d tell this imaginary story going around in his head in the middle of it all in great detail. And finally people would just say, ‘Shut the fuck up!’ Otherwise he wouldn’t stop the story.

KW: And you got back in touch with him at some point?

sc: Yes. Through relationships with Tracey and Robert King, an ex-Panther and one of the Angola Three. At one point Tracey and Brandon had gotten back together, only later to break up again on friendlier terms. Around this same time, he also became closer friends with King. King was living in New Orleans, where Ann and I visited him regularly. Brandon’s buying him dinners and hanging out. When I wasn’t talking to Brandon, he would try to get King to call me. King would call me up, ‘Hey brah, don’t turn him out. Come on, man, this guy’s a good dude.’

KW: In 2004 there was a Halliburton action he wanted to participate in?

sc: There was an affinity group in Houston, Texas that was going to do a lockdown, a civil disobedience action, against the war, at the Halliburton shareholder meeting. Some people I knew called me and asked if I would vouch for Brandon. I said, ‘I can’t vouch for him because he’s a wingnut.’ I told them what had happened at that anti-war protest in 2003. I thought he was unreasonable and might endanger people by making it personal between him and the cops. That’s why I can’t recommend him. They still went ahead and did the action and included him anyway. Everything went ok.

KW: Did he know that you didn’t vouch for him?

sc: Yes.

KW: Did that have a bad effect on your relationship?

sc: It had a very negative effect. He called me all hurt, ‘Why’d you want to turn me out?’ I said, ‘It’s your actions. I’m just being honest about it. I have to let people know so they can make a decision.’ Then after that phone call, we didn’t talk for months.

Search and Rescue

KW: When did you see him after that?

sc: He was living in New Orleans, and he came to Austin one time to visit me and my partner, Ann. He told us this crazy story about going to visit the FBI’s headquarters in New Orleans. He told the whole story in detail, driving through the gates; how he went in and he met with them; how they took him to this room. He gave them his name, his Social Security Number, and says, ‘I just want to know what information you have on me.’ The agents take the information. They leave him in this room, then they come back and say, ‘We don’t have anything on you.’ They escort him out he gets in his car and leaves.

We we’re thinking, ‘What the hell is wrong with you, man? What’s in your head?’

Eventually he moved back to Austin that year. That was the last time that I saw or talked to him until September of 2005, when he called me right after Hurricane Katrina — and said, ‘Let’s go get Robert King.’

KW: What did he say?

sc: He said, ‘We can’t let King die, and we should go do something about it.’ He said he was gonna go do something about it.

One thing that people don’t know about Brandon is that, although he grew up poor, his grandmother married into wealth, and he lives on sort of a trust. He gets money from his grandmother when he needs it. He’s never had a steady job since I’ve known him. He started a business once, ran it for awhile, and then stopped doing it. He could buy anything and leave anytime he wanted. So he’d bought a new small fishing boat to go to New Orleans.

KW: Did you trust him at this point?

sc: No. But I knew it was the right thing to do when he called. I thought, let’s do this!

Then I quickly came back to not trusting him. In stressful situations with him, it’s awful. I said, ‘I’m not going to go.’ I didn’t tell him that’s what it was. So he drove off by himself, and when he got to Houston (which is two hours away from Austin), I called him back and I said, ‘We’ve got to go; we’ve got to do this.’ It was for the greater good. I was just going to have to trust that we were going to make it happen.

I don’t want to go into the whole New Orleans story, but basically, in that very first trip everything went fine between us, even in incredibly stressful situations.

KW: So after that first trip, did you have more trust for him?

sc: Yeah.

KW: Do you want to talk about that? How did that develop; what did that feel like for you?

sc: Well, we encountered dead, drowned bodies together. We helped people try to find family members that were drowned. We saw massive destruction. The world destroyed. We’d gone through a lot of things together.

We took turns operating the boat and the gun. One person was always with a finger on the trigger, and one person was always on the boat. And we both cried together. I mean, we had horrible experiences together, and there was this kind of bonding that happened with that. Five days after the storm we returned home. Dejected and wiped out.

That’s when Malik Rahim another former Black Panther called needing support. That was when the white militias were coming, and the police were out of control killing black people. Brandon and I went around and gathered guns and headed back after being home for a day.

We’d taken the gun the first time because we didn’t want people to steal shit from us, but it turned out that wasn’t the issue. When we went back again on that second trip, that’s where we ended up in an armed standoff with the white militia. I mean, that story’s been told repeatedly. I talk about it in Black Flags and Windmills [pages 43-54, in the 2011 edition].

Then Brandon left in his truck to find King. I stayed with Malik in Algiers. Brandon tells the story in the movie Informant, with this heroic bravado — but it was just flooded, right? Thousands of people were dealing with the water. It was heroic in some ways, but let’s not overemphasize. During the whole episode I talked to him on his cell phone. He’s standing in water and calling me: ‘I can’t get anywhere, I can’t do anything.’ He’s saying, ‘I don’t know what to do’ — when finally, a FEMA boat offers to go get King, and then they brought him to the truck.

While he was doing that, that is when I pitched the idea to Malik about how could we build this organization — which became the Common Ground Collective. I’d been writing these notes and ideas up while Brandon was driving, the eight hours between Austin and New Orleans, in the days before. We get King, we stay for a couple of more days, and it’s real joyous and everything, and then we leave. I’m going back to Austin to get more supplies, but Brandon didn’t come back. He didn’t come back until early October.

Founders and Figureheads

KW: So it was during that absence that Common Ground got going?

sc: Yes!

KW: But he has been credited as a founder. I’m wondering if you can clarify.

sc: He had never organized anything in his life, right? He wasn’t there — so how could he be a co-founder, if he wasn’t?

What he did was — if you look at the documents, he’s not in any of the founding documents or communiqués. He’s just a coordinator until an article comes out in March 2006, called “Fifty Dollars and a Dream.” In that article, he inserts himself as a co-founder. And that’s where that narrative starts. He worked it. The media, being over-worked and lazy, just picked it up and added to it. He begged me to list him as co-founder, which none of the other people who really were ever did.

Much later, he had us saying it. But he didn’t found the organization. He didn’t pull in networks, call people, bring supplies in. He didn’t do anything. When he came back in early October it was an established organization.

That’s a minor story, but the reason I want to bring it up is because it diminishes other people’s roles — people who did amazing things there, who really did help establish the organization, like Sharon Johnson, Lisa Fithian, Kerul Dyer, Emily Posner, Brian Frank, Carolina Reyes, Jenka Soderberg, and Tyler Norman. They actually put the theory and the practice together into action. The macho narrative that has come up is that of the white-guy hero. Sharon, who lived there, was there organizing from the beginning and often gets written out of the storyline — heartbreakingly.

KW: Once he came back, what was his role?

sc: Because of our search and rescue mission for King, that we took up arms against the militia, and because of inherent patriarchy — if you want to use political language — Malik gave him and myself more power and trust, above anybody else who showed up. I had started an armed security team after the first encounters. Malik and I had a relationship of five years before that, from 2000. Brandon had just met him, but we had done all these things so Malik and Sharon put him in high regard.

When he came back again, Malik put him in charge of the 9th Ward project. We started in Algiers, but we were spreading out to other places like the 7th Ward, the 9th Ward, down in the Houma Nation, etc. Setting up clinics and distribution hubs, then leaving them for the people to run themselves. He was given leadership of what became ground zero.

KW: How did he do in the role?

sc: Well, Brandon did a lot of shaking hands and meeting people. He was really good at that, but he didn’t do a lot of the dirty work. He would go out and meet a preacher or community leader, but he wasn’t doing the cleanup or the dishes like other coordinators. He directed people to those tasks. He appointed himself the spokesperson and made sure the media talked to him only. If you notice, there are a lot of articles that came out in 2005 and 2006. He’s in a lot of those. If camera crews came, he wanted Common Ground volunteers to direct them to him.

I only found out about this later, in 2008, after the informant thing came out. I started to talk to all these national journalists who would say, ‘I was down in New Orleans and I was interviewing people; I wanted to interview you, but Brandon told me that you, Lisa Fithian, and Malik wouldn’t do any interviews and that we could only talk to him.’ This is the New York Times, Washington Post, as well as radical media and grassroots media that we’re talking about. He made himself a figurehead.

In the timeline, I’d left Common Ground at the end of October 2005. My plan was to come back every few weeks, every few months, and deal with internal stuff, because I was working with the coordinators on support work and administration from Austin. I’m out of my head, you understand, from post-traumatic stress — bad. Sharon has it, Malik has it, a lot of people who were there in the very early days have incredible PTS. It’s unimaginable to think about right now, how bad it was then.

During all of this, we’re always having ongoing tensions with this other organization that’s supposed to be a coalition called People’s Hurricane Relief Fund, which we’re part of. Some of their leadership were black nationalists who were criticizing our mostly young, white volunteers and wanted to control all the radical grassroots efforts. They’re raising tens of thousands of dollars in Common Ground’s name, but we don’t see the money. It’s just that some people control the purse strings and are also taking credit for our work. It’s classic internal squabbling, except it’s in the middle of a crisis. The head of their organization is this old-school black revolutionary, Curtis Muhammad, and the relative figurehead of Common Ground is Malik. They had a decades-long relationship. When issues would break out between our organizations, they would meet and sort it out without anyone else’s consent, and we were told to leave it alone. It was not healthy or productive.

In December, Brandon starts haranguing me repeatedly with calls saying, ‘You’ve got to write a letter to PHRF about this!’ The issues with PHRF aren’t resolving, so I write this letter that calls them out. Which is not what you’re supposed to do. Power dynamics, race relations, and of course miscommunication are involved. My letter was addressed to Curtis and his two sons, who were in control of PHRF. It also caught some supposed comrades of mine that before that I had great respect for. Anyway, I write this inflammatory letter through a small internal email list with about twenty people on it. PHRF and their supporters go ballistic! I was accused of COINTELPRO tactics. The next day I get two death threat calls. I immediately go back to New Orleans with a bodyguard. Common Ground and PHRF people are furious at me. I’m worried that internecine warfare is about to break out, that random volunteers might get shot.

I take full responsibility for that letter. I wish I had never written it, but I did. I wouldn’t have if Brandon hadn’t called me fifteen times a day for two weeks — ‘Write this letter, write this letter’ — to fuel the fire, though! In going back, I have had to ask if his insistence was just his neurosis, or was it more sinister? He never took any of the heat for it.

KW: How did that situation wrap up?

sc: I tried to make amends, as much as I could. I apologized publicly and privately. I lost a few friendships over it that I grieved about. I regret the letter, even if it contained some truth.

About four months later — which in post-Katrina time was a huge amount of time — the People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond, who started all the anti-oppression trainings in 1970, and people from the Catalyst Project in the Bay Area facilitated a meeting between two people from PHRF and Lisa Fithian and myself from Common Ground. It was heated, to say the least. It took about six or eight hours — with seven facilitators to iron out issues. We weren’t trying to sing kumbayah together, we were just trying to get through tough issues. Neither Malik, Curtis Muhammad, nor the people who had been my long-time comrades participated. Kali Akuno, who was about to become the executive director of PHRF, and some others came instead. I’m glad they did. In the end, it came out really good. We actually were able to solve a lot of issues, clarify a lot of miscommunication, and really be able to smooth things out. There was a lot of negotiation and clarity.

For myself, personally, there was vindication in it, because actually what I’d written was true. This was not my interpretation of it — it was confirmed by Kali and others. It still didn’t make things right, but it smoothed things out. We still had a tenuous relationship, but it was better. Shortly after that, PHRF split into two organizations — fighting over over financials, control, and direction. Sadly, they ate themselves up internally.

Years later, I was able to make amends with Curtis and Althea Francois from PHRF, but not the other two. Kali and I remain comrades.

Drama and Dysfunction

KW: Looking back, people have said that Brandon was always a disruptive force. Can you say more about that?

sc: His ego was always front and center in everything. He could be a vortex, sucking the room’s emotional energy in. He would take credit for others’ work. There were three other core organizers who all did amazing work in the Lower 9th Ward — Justin Hite, Michele Shin, and Kim Ellis — but you don’t know about them. They didn’t talk to the media all the time. They were just doing the work, day-in, day-out. Facing arrest, facing police brutality, and organizing.

One of the issues that I had to come back for was that Brandon was sleeping with lots of volunteers. It was his pattern. It was inappropriate, but he wasn’t a sexual predator. He didn’t sexually assault people; there was consent, but there was a power dynamic that was not healthy. For a high-profile thirty-year-old coordinator to sleep with a twenty-year-old volunteer was not appropriate. And then there was the drama around it all.

KW: Do you feel he was manipulative or dishonest in those relationships?

sc: Oh my gosh, yes! Absolutely to both. He can’t tell the truth. His knee-jerk reaction is to tell you the story he thinks you want to hear, or the story that makes him look good. During this time, I’m talking to him on the phone ten or fifteen times a day, because he’s calling me constantly about things. I’m brought to New Orleans, and we’d have these coordinator meetings with twenty or thirty people, and just go: ‘Look, you can’t do this.’

KW: Did Common Ground have a policy about that?

sc: Not at first. We’re starting this organization from scratch, so we’re building all of these guidelines and policies at the same time.

KW: Was that a problem elsewhere in the organization?

sc: Yes. Brandon wasn’t the only person doing that kind of thing. Patriarchy was a subtle but big problem in Common Ground — unrecognized power given to men. He wasn’t the only one. There’s a list of them, but a lot of other people, we would remove them from the organization. One of the things that we did, because we couldn’t rely on the police, is that we would threaten the use of force, or even use force against people to remove them for violations — especially around sexual assault or rape.

KW: Why wasn’t he thrown out the same way?

sc: That’s where it’s complicated. I think the PTS, I think the power dynamics, the fact that he wasn’t sexually assaulting people.

Let me say this: No person came forward and said, ‘he sexually assaulted me.’ At one point we had an anonymous discussion group on our website. There were a couple of threads by an anonymous person that made allegations of sexual assault and rape. They were saying, this guy’s raping women all over the place. Then they started posting on Indymedia. And you have to understand, it was not verifiable at all. It was very inflammatory language and happened occasionally about other issues within Common Ground. Women and men in the organization took it as COINTELPRO being used against us.

So, I used my connections with Indymedia all around the world to take it down, on server after server after server, because Brandon asked me to. I still stand by that, because you know, no physical person ever came forward and no advocate for a physical person ever came forward and said, ‘he physically assaulted me.’ It was always definitely inappropriate power dynamics that caused drama, but that would be it.

The other issue was the more paranoid he got—which a lot of us were getting paranoid, because we were under siege. To contextualize this: I thought I was going to die. I didn’t think I was even going to make it out of the first few weeks. Not just me, but actually the first handful of people. I was saying goodbye to people, ‘We’re going to die. This is it.’

At this point scott started to cry.

KW: Do you want to take a minute?

sc: Yeah.

After a few quiet moments, he began again.

sc: We were anarchists and radicals trying to build power from below. We were under attack from the state, still, even after we had protection from the media and people coming in droves. When we finally knew we wouldn’t be killed, we still were under siege. COINTELPRO repression was in the back of all our minds. Homeland Security was everywhere in all of their incarnations. We we’re asking ourselves, are there informants? Provocateurs? What’s wingnut behavior, and what’s targeted destruction? All in this incredible crisis; not in a rational, reasonable, or safe place to sort it.

KW: How do you know what counts as wingnut behavior under the circumstances?

sc: You can’t! We couldn’t; there was no rational way to sort it. Brandon got protection in all of this from that siege mentality. When a majority of volunteers came in for a two-week stint, they would never know any of this was going on. There were internal coordinators meetings they weren’t part of that kept the organization running, and we didn’t need 400 people trying to make decisions.

The more paranoid he got, the more power he asserted over the project. If he felt like he was under attack, because people called him out on being a jerk, he would fire volunteers. Just remove them or kick them off to other projects.

He also did this thing where he made sure he surrounded himself with people who were his ‘followers.’ Lisa Fithian referred to them as his henchwomen. He definitely had a crew of women that backed him throughout all of this.

He got protection in all of those pieces. When I think about that now, I don’t know how we would’ve done it differently. We couldn’t sit in a meeting with 200 or 400 people who were going to be there for two weeks, and explain all of these things to them. You know, it had to be people who were going to be there for the long term.

Venezuela

KW: Brandon has pointed to the trip to Venezuela as a turning point in how he was thinking about politics. What do you know about the trip?

sc: The organization Pastors for Peace invited Malik and myself to go to Venezuela in September 2005 to meet with people in the government and share information on hurricane relief strategies. We knew that the Chavez government wanted to use it for propaganda. Brandon wasn’t even invited to go at first. Then, sometime in December, the trip changed. When I came back to New Orleans in January, I found out a new delegation, including Brandon, was going without Malik or me. Common Ground sent four people, Carolina Reyes, Emily Posner, Don Paul, and Brandon.

They get to Venezuela to spend about a week. The doors are open, they’re meeting with the government ministers and agencies. It goes really good, although there is some concern from the government about Brandon. The Chávistas really welcomed them with open arms in the barrios. They had their own security patrols — not the state — protect the delegates and made sure they were safe. Lots of media, everything went great.

Then the rest of the delegation left, but Brandon, on his own, decided to stay. The Chávistas didn’t trust him; they thought he was CIA from the beginning. So they put him under guard at the hotel and wouldn’t let him leave without them.

How do I know this? Because he called me on the phone from Venezuela three or four times a day, freaked out. He sounded like he was out of his mind. He kept telling me, ‘They won’t let me out, they have me sequestered. I don’t know if they’re going to take me out and kill me.’ All I can go by is his words. So he’s says, help me get Robert King here. Because King had traveled in Venezuela before, people had respect for him. King agreed and flew down, and the doors started opening again. I don’t know what happened with Brandon then — you have to ask King.

If you could have the conversation I had with him in 2006 about it, versus what he tells in the movies and today — that he was going to meet FARC rebels — they’re different stories. But that’s the story he would want people to know: He wanted to be a pretend revolutionary. But I think that it never really happened. I think he was out of his head, and that maybe in his paranoid fantasy it was real.

Leaving and Returning

KW: After he came back he was dismissed from Common Ground.

sc: Yeah. By April or May, we’d said, you’ve got to go. You’re out of your mind, you’re totally dysfunctional. You’ve got to go home. It wasn’t dramatic.

KW: Did it seem like he left on good terms?

sc: Yeah, he was ready to go. He had put a pretty good stint in. He left — it was very mixed bag. He wanted out. A lot of people sighed with relief that he was leaving because he was not being effective as an organizer in any way. Some people really did not like working with him at all. He was too conflictual, and he was irrational. And he spent a lot of time talking to the media when other work needed to be done. Then there were some young people — including women — who loved his authoritarian bent and wanted him to stay.

When I would see him back in Austin, we’d sit down together, like you and I are sitting together, and just cry and cry, and just say to each other, ‘I know.’ Because we did know we had survived some hell.

During this time Brandon supposedly was going to start this organization called Critical Response, with other Common Ground volunteers participating, and it was going to go help people in Lebanon during the war. What’s interesting is that nobody was actually involved in it. He wrote this communiqué and he had me to rewrite it and sign it myself. And I did, as a favor. It’s a public letter talking about how this new organization was forming from ex-Common Ground volunteers — even though Critical Response had done nothing.

KW: Why did you think that was a good idea?

sc: I had reservations. But it was just aid work. And I’m not making rational decisions about things. I couldn’t even hardly communicate with people. I was very isolated. I was trying to figure out what I was doing and who I was. I felt out of my body, I had so much PTS.

The organization never happened. It just went away.

KW: How much later did he come back? How did that affect the Common Ground?

sc: He came back in January of 2007. The organization was not healthy. We had been through months of terrible accountability processes for things, burn out, illness, a waning influx of volunteers, PTS, lack of focus, equipment was being stolen. You name it, we suffered from it.

Brandon politicked Malik to let him come back in and run the organization as interim director. Malik was in bad mental and physical health and relented.

There were a few of us who were against it. Lisa was one of them. She had butted heads with him the whole time they were there together. She has her own set of issues, but she would challenge him. There were a lot of powerful women, but hardly any of coordinators of any gender would challenge him on a regular basis. Lisa didn’t always get backing in it, but she did it. That is one of the biggest regrets I have, that I didn’t always give her enough support. Because it was obviously a power struggle between them, and she was right on so much of it.

He came back in January, and he proceeded to fire all these non-paid coordinators, mostly women, because they refused his authority. He didn’t have other people to replace them, or a plan, or consent from any of us advisors. Important projects were being wiped out.

Then he started a new war with the New Orleans police. We were working with other groups on a campaign against police brutality, where people could anonymously report police brutality. Then we would try to follow it up. Brandon didn’t think it was moving fast enough, so he got a volunteer to make and post flyers with his name and phone number on it instead of the group’s. They said: ‘If you have police abuse, call me!’ This was done without the knowledge or consent of anybody. Just like before, he made the issue him versus the police. Everybody was furious about it because it brought so much unnecessary heat again. I’m talking about the cops harassing on a scale that hadn’t happened since the beginning of the organization: pulling volunteers over, raiding facilities, and pointing guns at people.

As all this is happening, money disappears, or is not accounted for. Projects are going awry. People that he perceives to be living off the organization’s good will — and there are people who sponged off us because we had free places to live and free food: crusty kids, drunk punks, train hopping kids from other places, and the occasional New Orleans resident with issues. Brandon brought this armed patrol that was ‘his’ crew around. They beat the shit out of people and were threatening people with guns. Maybe it needed to happen, but it wasn’t consented upon with anybody else. It caused so many problems. People left the organization in droves — long-term coordinators and volunteers, in addition to the people he ‘fired.’

Finally in April a few of us coordinators came together in New Orleans and said, ‘You’ve got to go. You cannot be here! It’s over.’ That was his last stint. He was never invited back.

In 2010, through a Freedom of Information Act document, I found out that he had been working for the FBI, getting paid in August of 2006. That means when he came back to Common Ground as Interim Director, he was on the FBI payroll.

Austin

KW: After New Orleans, did you have much contact with him?

sc: I would see him from time to time in Austin. We didn’t see each other that much; and when we did, we would just cry together. It was a pretty heart-breaking time. We were both dysfunctional.

In 2007 and 2008 Brandon was meeting at this coffee shop called the Green Muse with this man named Riad Hamad, a longtime peace activist in Palestinian Solidarity, trying to get money to send to Palestine to do healthcare, education, road infrastructure. Basic aid work. Brandon occasionally called me to meet. Two times I went, Riad was not there. But there were these other Middle Eastern men. Once he pulled me aside and bragged, ‘These guys aren’t anarchists, they are real revolutionaries. They’re illegal immigrants in this country.’ My reply was, ‘Don’t get involved in politics that you don’t know about. You think it’s one thing because you see this surface, but you don’t see all the intricacies. If you pick one faction to give aid to, then maybe this other faction won’t ever get it or maybe they want to use this for control. You’ve got to be careful about that stuff. You don’t know the politics.’

Then Riad’s house was raided twice by the FBI. They took a lot of documents, but never charged him with anything. It was stressful for him. Shortly thereafter, in 2008, it looked like Riad was killed — but now we think that he took his own life to stop the persecution.

KW: Is this around the time Darby tried to recruit you for an arson attack?

sc: That was before — around October of 2006, in the fall sometime. I was with this organization, Anti-Racist Action. We were thinking about doing some protest against this libertarian bookstore called Brave New Books because they had some nativist and anti-immigrant books. Brandon was not part of ARA, but I told him about it and he said we should do more. ARA had decided against giving them attention at all.

Brandon developed this plan where he wanted to set off smoke bombs or something — I don’t know the details — and then the sprinklers would go off and ruin all of their inventory. Then we’d ride off on his motor scooter in the alley. I think I literally responded with, ‘That’s fucking stupid! Strategically, this is a dumb idea. This bookstore is nothing. There’s a long list of things I would burn down before I ever tried to burn down this bookstore.’ Also this building has a lot of people in it who are not related to that bookstore. What if something happens to them? He pressured me and I refused to do it. I didn’t do it, so he tried to enlist this friend of mine instead.

I didn’t know that at the time. She has her own story around it, but very similar. She said flat out, ‘I’m not going to do that. That’s just fucking dumb.’ She’s a long-time anarchist organizer who could see the stupidity.

At the time, I took it as just more of the same stupid ideas that he had before. It had evolved from shooting people at a Wal-Mart, to killing the CEOs, to doing this. That’s where I was in my head with it. It should have been an alarm, but it wasn’t.

RNC

KW: Were you in touch with him in the lead-up to the 2008 Republican National Convention?

sc: No, he was very isolated. He was staying at his house a lot. He wasn’t getting out and doing things, as far as I knew.

KW: Did you hear about his interest in going to the RNC in 2008?

sc: He told me he went to the meetings in Austin, and he was thinking about working on the medical teams in the spring, but that was it.

KW: Did that surprise you?

sc: Yeah. He had PTS really bad. I told him I thought it seemed like a bad idea to go into a situation where they could set off concussion grenades that could totally set him off.

I didn’t know he was working with Brad and David at the time. I was close with Brad. I’ve known him since probably about 2002. Brad was hanging around Treasure City, this anarchist thrift store that I had started. He was coming to volunteer with me on the shift, and we’d talk a lot about things. But I wasn’t telling him about Brandon’s dark side, and he didn’t tell me about their meetings.

KW: You didn’t know that Darby was meeting with them?

sc: No. Not until a bit later, maybe around May or something. Then I knew that he was meeting with them, because there was a crew of people that were going to go, and he was going to be a part of it. I was totally surprised. Because they were all much younger than him, most people were newer to activism. Also that he would want to go.

He and Brad went to a preliminary meeting in the spring. Lisa Fithian, who was organizing on the ground in Minnesota, called me asking why he was there. Like I was his keeper. I said he told me he’s going to be on the medical team. She said he didn’t join medical, he went straight to the communications meeting. She’s straight up said, ‘I do not trust him,’ but they let him in.

KW: So what did you think when you heard about Crowder and McKay getting arrested?

sc: During the Republican National Convention, Brandon was calling me relentlessly, and I was communicating separately with another friend, James. Brandon called in a panic about something Brad and David had done, although he didn’t say what. ‘They’ve just done some shit that they’re going to get into big trouble for.’ James was saying that they’re going to get us all in trouble. I reminded them both that the phone was not secure. I didn’t know what to do. Brandon kept saying, ‘Don’t support them, when you find out, don’t support them.’

Then they got arrested and charged with terrorism. By then I knew they made molotov cocktails for property destruction, because all the Texas people had come back from the RNC. Grand jury subpoenas were being issued across the state. We didn’t know how wide it would go. Publicly we supported them, but behind the scenes we were really mad at them for bringing down heat on all of us!

Then David Hanners from the Minneapolis paper Pioneer Press wrote this small piece about the RNC and mentioned an informant named Brandon. We’re feeling that we’re under siege, that we need to protect ourselves. A few of us think that the state is trying to divide us by feeding misinformation to the media so we’ll turn against each other in court. I talk to Brandon about doing something about it and ended up writing a public letter in support of him and the others who had already been served with grand jury subpoenas and talking about how we can’t let rumors divide us.

About two weeks later, David McKay’s father brings us about sixty pages of un-redacted FBI documents. All of these names are in it: from the RNC, Austin, New Orleans, and beyond. The only name absent was Brandon’s. For example, there’d be a meeting where there were five people; all the names are listed except his. Or he was reporting conversations that only he and I had. It became clear.

Throughout, Brandon makes allegations against people who had nothing to do with the RNC. For example: this woman Kate, who wasn’t even related to Common Ground, but had lived in New Orleans — he mentions her working with the ALF (Animal Liberation Front). She’s wasn’t an animal rights activist, not vegan and never has been. It was full of inflammatory lies like that. Why would he even say it?

There were many intricacies to the RNC story we didn’t know yet. For instance: that the FBI arrested David when he was naked and asleep, an hour before he was getting on a plane to leave; that Brad had already been in jail for a week before the raid; that they both had changed their minds about the molotovs; or that Brandon was a paid informant. We didn’t know any of these details yet.

KW: Did you confront him?

sc: Yes. After RNC, he kept saying that he had something to tell me, but never would. The last time we met, we’re sitting, making idle conversation. So I ask, ‘What’d you need to tell me?’ He answered, ‘It’s no big deal. I can tell you later. I’m too stressed.’ We made small talk for a few more minutes, then I get up to leave. He says, ‘Hey man. . .’. He hesitates again, then says, ‘Fuck it. I’ll call you later.’

I get out to the parking lot and I call him. I said, ‘I know. I know you informed on all of us to the FBI. I’m going to give you one chance tell me why. It won’t change what I think.’ He says he knew Brad and David built molotovs, and he had to do something about it. It was a weak justification. I said, ‘When you brought bad ideas to me, I didn’t turn you in, I talked you out of them; why did you turn them in? Why didn’t you try to stop them? You have more power than them. You could have physically stopped them. You’re physically stronger than both of those guys.’ He came back with, ‘Brah, it’s more complicated than that,’ followed with, ‘Why do you want to persecute me, man?’ — trying to turn it around. Then he says, ‘We’re in a historic situation, brah. You’re on one side of this, anarchists and revolutionaries, and I’m on this other side. We could work together on something. You don’t have to make it into where it’s you against me.’ To him it was a game or a movie, or we were having a minor disagreement. I remember saying, ‘What’s wrong with you? Two people might go to prison. They’re facing terrorism charges. This is going to be the last time we speak.’ I told him we were going to out him. Then he said, ‘In ten minutes, I’m going to post a public letter that explains everything.’ I hung up on him and that was it. It was the last time we spoke.

Shortly thereafter I wrote my second statement, saying that I’d made a giant mistake and that I had been lied to. I apologized to the public for defending him.

Taking Stock

KW: Did those revelations cast his or your actions in a different light for you?

sc: Yes, at first we were all trying to sort it all; taking inventory of past conversations and his actions. For me the bookstore incident, the PHRF letter, the communiqué I disseminated for Critical Response, and his visit to the FBI in 2004 — that really made me reassess. He had tried to get me to commit a crime where I could have ended up in prison. Was the FBI behind it all?

Then, all of a sudden, the stories started coming out about all the other people he’d approached, like one of the key organizers and a cofounder of Common Ground, Suncere Shakur. Brandon tried to get him to blow up some confederate statue and burn some developer’s project in the Lower 9th Ward in response to gentrification.

KW: Do you think that he had been fishing for a while?

sc: I still don’t know. It’s still speculation, right? Until I got my FBI documents in 2010 there was a fog of how deep it all was. I first heard in 2006, through the Angola Three’s lawyer, that I was listed as a domestic terrorist, animal rights extremist, and environmental terrorist. Brandon was around the whole time. I kept going back in my mind. Did he flip in 2004? 2002?

No charges were being brought, but the FBI, the ATF, and the Texas Rangers were at my door. The Rangers were making the rounds after an arson at the Texas governor’s mansion in 2008, three months before the Republican National Convention. Somebody had burned the whole damn thing down with a molotov cocktail. It was ironic because none of us knew who did it, but everyone suspected Darby because of his confused politics. This was before he was outed.

All through 2009, we still don’t know what’s happening. Our ad hoc group, the Austin Informant Group, is doing media to battle the FBI and Brandon’s lies and supporting Brad and David. We decided to do these FOIA requests to the FBI on about thirty or forty people and about forty organizations, protest events going back to 2000, and local radical spaces. Austin People’s Legal Collective directs it. We submit them to offices all around the country. 95 percent come back with nothing. One group, Anti-Racist Action, got 600 pages, which was mostly about national. I got a little over 600 pages. When I went through them by year, I see Brandon beginning to give information in about May of 2006. Then around August of 2006, he receives his first payment, but you can’t see how much it is. We know from the trial transcripts it was about $16,000 per year, which is not very much for an informant. But he wasn’t doing it for the money.

KW: Why do you think he was doing it?

sc: That’s the million-dollar question, right?

I think it’s multi-layered. In one way, he wanted to continue being a hero. I also think, he thinks that he’s smarter than all of us. That’s a running theme with him, that he is way more cunning and way more smart than most of us. (laughs) He thought he could play both sides. He loved spy versus spy stuff. He would always talk about it. I could see him just being intrigued by the espionage.

At another level, I think that the FBI used him. I think he turned information on Riad first. I think that’s the operation he chose. And later, they started to ask a lot of questions about me. They already had ongoing investigations of me since the late ’90s and hadn’t been able to get me on anything. Now they had a chance to have someone who’s closer to me. Not because I was important, but it was how they operated.

This is all speculation. He’s lied so often, I don’t think he knows what’s the truth is anymore.

Trials and Threats

KW: What happened with Brad Crowder and David McKay?

sc: They were both facing up to twenty-five years for building the firebombs. I think the conviction rate if you go to federal trial was something like 95%. The feds really force innocent people to take plea deals as standard procedure. They treat it like football. Someone has to lose.

Brad, who had been locked up during the RNC on unrelated protest charges, took a non-cooperating plea deal for three years. David wasn’t offered the same deal, and decided to go to trial. The FBI flew in their top prosecutor. A few people were going to testify on David’s behalf. I initially refused to testify, but did an affidavit with all the past information on Brandon. That’s because David’s lawyer told me: ‘I don’t know how to say this, but the FBI is gunning for you’; ‘The FBI wants to get you.’ According to Brandon’s own words, Brad and David were “collateral damage” in all of this. It was unnerving.

In the trial, the state and Brandon both lied repeatedly. It ended in a mistrial. The jury didn’t find Brandon or the FBI credible. David was free until they set a new trial. I realized then that, whatever the risk, I needed to testify against Brandon. I couldn’t let him lie. The feds were spinning the media, saying Brad and David were terrorists and Brandon is this hero who stopped it. He, at the least, encouraged and created a macho climate and, at the most, entrapped them by his actions and the tone he set. The legal distinction is stupid and vague.

As I’m about to fly out for the new trial, Lisa calls and says, ‘David took a plea deal.’ So it’s over, it’s done. David got four years.

KW: Isn’t there some sort of post-script, about Darby getting threats?

sc: Yeah, this woman Kate Kibby. She allegedly made a threat against Darby via email while all of this was going on. A few months later the feds tracked her cell phone and snatched her off the street and put her in a van — creepy, rendition style. They asked a lot of questions about me, Lisa Fithian, and some others she didn’t know.

She was someone none of us knew at the time. They offered her the option to become a paid informant for the feds. She was a traveler kid and a photographer, and they offered to get her a show in New York also. She refused. They charged her instead with threatening a government agent. She was facing ten years in prison. She took a trial rather than a plea, and won.

The trial took place here in Austin over two days. Darby and his handler, Tim Sellers, both testified. The jury found neither credible (and said so). She won.

KW: When was this?

sc: In October and November, 2009.

KW: Did you attend the trial?

sc: I missed the first day that Darby testified, but was there the second.

KW: What did Darby say in the trial?

sc: I can only say second-hand, but I heard it from three eyewitnesses.

The state tried not to call him to the stand. When they did, he gave his account of what happened pretty matter-of-fact and succinctly. The defense then asked Darby about a lot of other things — his letter and the fallout from it online, the allegations that he had tried to get others to also commit crimes, his behaviors, etc. Then the defense pulled out a really thick pile of printouts from online forums /news comments sections where Darby was threatened by thousands of people. Some were worse than Kate’s alleged threat. The defense compared his open letter to ‘sticking a candy bar in an ant hill.’

Then they questioned Sellers, his FBI handler, on the stand. He basically contradicted most everything Darby had just stated. He also said that Darby had gone rogue with the media, and they had tried to censor him. He finished with, “Brandon was of no use to the FBI anymore.”

The prosecutor, in his closing statements, also hung Darby out to dry by not backing him up on anything about his character or his patriotism or useful work with the FBI. He tried to distance Darby from the FBI.

The jury acquitted and the state did not appeal.

KW: What do you make of the jury’s decision? Why wasn’t the case a slam dunk for the prosecution?

sc: The jury had heard all of these things about Darby from the defense even if it was supposed to be struck from the record. They still heard all the contradictory testimony from Sellers and Brandon. Kate Kibby was honest and amazing on the stand. She told the truth — even when it was uncomfortable. She talked about the FBI trying to entice her to be a snitch and her ‘crime of passion,’ as she called it. I know the truth doesn’t always win in court, but in this case it worked. Sellers looked defeated.

Then and Now

KW: Do you still hear from Darby?

sc: He would still email me years later: ‘Hey bro, what’s going on? Let’s put this aside and continue to work together!’

After Haiti broke, he wrote me this email saying, ‘I can get you all the resources you need, because I know you can make it happen in Haiti.’ He was dropping all these names — like the director Jonathan Demme — as if it made him credible. ‘I won’t even be a part of it. I just want you to do it.’

Then I’d get an email two weeks later saying, ‘You’re a terrorist! You lead young people like me into things, but you never get in trouble. You always walk away from it, while we get trouble.’

I have never answered him, ever.

On Twitter, he’s called me a domestic terrorist over thirty times in the last few years. I just ignore him — partly because he is trying to suck me back in, and partly because I know that he hates it when people cut him off. He will try anything to get you to respond. He will try to get back to you. That’s what he would always do with his ex-girlfriends. That’s the only personal gratification I get out of the whole thing.

KW: Knowing what you know now, what do you wish that you personally had done differently?

sc: There’s a couple of things.

One, I wish I’d cut him off earlier on and just said goodbye, and not let him manipulate his way back into place before, pre-Katrina, when he would work his way back in. I have been known to have a tolerance for difficult people.

The second thing is, I wish we had felt secure enough, and had enough breathing room at Common Ground to be able to talk about these issues more openly. There wasn’t. If we did it again, would it have gone differently? I wish, because that gatekeeping of those stories protected him. Then later, I protected him by still backing him in subtle ways, by not telling Brad all the bad stories about Brandon.

I didn’t tell those stories to people because I still had this weird attachment. There’s this post-traumatic stress thing that happens, where — I don’t know what it’s called, but I read about it in a book on Vietnam vets — where people in a foxhole together, facing life and death situations, that bonded them. Then later, they would see their foxhole buddy go on and do horrifying things like rape women or kill children. It created a dissonance in them, because they had this connection together. I definitely had that with Brandon because of the trauma we faced together in New Orleans. Even after he was outed as an informant, this bond hurt.

KW: Collectively, what lessons do you think we should take from this?

sc: For me, it’s interesting, because I probably broke three of my principles in New Orleans.

One is, you never leave anybody behind. And I’d done that at one point, where I was leaving people to die at the beginning, and felt horrible about that.

The second was, I had promised myself that I’d never be in an open collective again because they’re always messy. It becomes the lowest common denominator. And Common Ground, we could form it no other way. There’s no way to do it. And that became a big mess.

And the third thing was the gatekeeping. I wish that we had had more transparency. I wish there were some mechanisms for doing that.

I’m sorry, actually the fourth thing that I want to talk about, was that bad behavior is bad behavior — and kick people out. Which is another thing that I had with other organizations. I kicked people out of organizations before. Not directly myself, but we had said, ‘Look, you’ve got to go.’ We had policies in Austin that, basically, if you were disruptive you’ve just got to go. I wish that when he had acted on bad behavior, I just had cut him off and just gone with my gut instinct, which said that this guy’s problematic. Don’t let him in. No matter what he does, just don’t let him in. Because I think things would have looked different.

But it didn’t happen that way. It happened the way it happened.

KW: Any lingering doubts?

sc: There’s always some. What are ways we can navigate trust and confidentiality? Should I have told people that Brandon had approached me about property destruction, given the context of his other bad behavior? What about others he approached? What about all the others who’ve approached me and haven’t done anything, and never will — because sometimes it’s just a phase or exploration?

I’ve been approached in my life, and I have approached people that I trusted, about sabotage — you know, property destruction. It has its place. My rule was to not talk about it, which I still follow. When people are new to activism, it’s really a common thing for their emergency heart to kick in and think extreme action is what’s going to make it, without any context, experience, or strategy. It’s visceral. So I don’t know. That’s a lingering question.

KW: On the one hand, he was behaving irresponsibly. And on the other, you don’t want to be the security threat by talking about him behaving irresponsibly.

sc: Yeah. Which is always really messy to navigate.

KW: Briefly, your thoughts about the movie Informant?

sc: It’s mostly a depoliticized version of some of the events. It’s well done for being a portrait film, and a great companion to Better This World, which covers some of the same events. It distorts the story to tell a heroic arc, so you can see somebody rise and fall. That’s the filmmaking tension and surprise of it. Jamie Meltzer did well calling Brandon’s story into question without doing it bluntly, by letting him hang himself as he talked. Brandon lies in some of the points beyond just distorting the truth.

The film also reminded me of how the right-winger Andrew Breitbart (and by extension people in his camp) used Brandon as if he was a prop in a show. Andrew trotted him out every time he needed him to bash the Left on some issue. He’d paint Brandon as some authentic leftist who saw the light, then make him go back to his seat. It sounds like a bad church revival. (laughs) I don’t think Brandon could even see how he was being used, since he also benefitted from it. Now he is accepted in this fringe right largely without question — which has always seemed weird to me. He gets to be a hero for lying, without any sort of accountability.

On a more personal level, when I saw the movie, it triggered me immensely. I had never seen the footage of myself at Common Ground. I didn’t even know it existed, and it was really hard to see at first. I can see how different I am now. Also, to have to relive some of those traumatic events he and I went through together, and to have to remember how he could be a good person and be completely narcissistic at the same time. People call it charisma, but if you notice, it draws the arc back to him every time — much like qualities associated with sociopathic behavior. So it was mixed feelings.

I think it does a disservice to Common Ground to talk about how much he did there without acknowledging the hundreds of good, core people who did amazing work — but you never hear their names. The focus is the story about this dysfunctional man instead.

Bios

Kristian Williams is a member of the Committee Against Political repression, and the author of Our Enemies in Blue: Police and Power in America, American Methods: Torture and the Logic of Domination, and Hurt: Notes on Torture in a Modern Democracy. Most recently, Williams helped to edit the collection Life During Wartime: Resisting Counterinsurgency. He lives in Portland, Oregon.

scott crow is an anarchist community organizer, writer, strategist, and public speaker. He was a co-founder of Common Ground Collective, Treasure City Thrift and other cooperative projects over the last twenty years. He is the author ofBlack Flags and Windmills: Hope, Anarchy and the Common Ground Collective. He lives in Austin, Texas