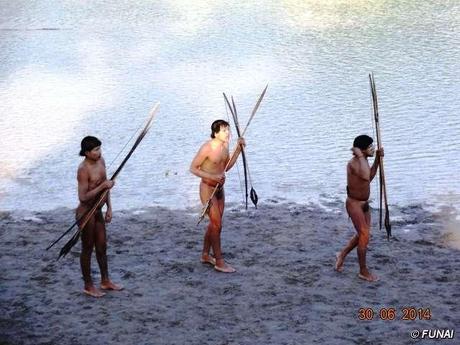

Seven uncontacted Indians made contact with a settled Ashaninka community near the Brazil-Peru border in June. Authorities have treated them after an outbreak of flu. © FUNAI

Highly vulnerable uncontacted Indians who recently emerged in the Brazil-Peru border region have said that they were fleeing violent attacks in Peru.

FUNAI, Brazil’s Indian Affairs Department, has announced that the group of uncontacted Indians has returned once more to their forest home. Seven Indians made peaceful contact with a settled indigenous Ashaninka community near the Envira River in the western Acre state, Brazil, three weeks ago.

A government health team was dispatched and has treated seven Indians for flu. FUNAI has announced it will reopen a monitoring post on the Envira River which it closed in 2011 when it was overrun by drug traffickers.

The emerging news has been condemned as “extremely worrying” by Survival International, the global movement for tribal peoples’ rights, as epidemics of flu, to which uncontacted Indians lack immunity, have wiped out entire tribes in the past.

Brazilian experts believe that the Indians, who belong to the Panoan linguistic group, crossed over the border from Peru into Brazil due to pressures from illegal loggers and drug traffickers on their land.

Uncontacted Indians face pressures on their land due to illegal logging, drug trafficking and oil and gas exploration (picture taken in 2010). © Gleison Miranda/FUNAI/Survival

Nixiwaka Yawanawá, an Indian from Acre state, said, “This news proves that my uncontacted relatives are threatened by violence and infectious diseases. We already know what can happen if the authorities don’t take action to protect them, they will simply disappear. They need time and space to decide when they want to make contact and their choices must be respected. They are heroes!”

Uncontacted Indians in Peru suffer multiple threats to their survival as the government has carved up 70 percent of the Amazon rainforest for oil and gas exploration, including the lands of uncontacted tribes.

Plans to expand the notorious Camisea gas project, located in the heart of the Nahua-Nanti reserve for uncontacted Indians, recently received the government’s go-ahead, and Canadian-Colombian oil giant Pacific Rubiales is carrying out exploration on land inhabited by the Matsés tribe and their uncontacted neighbors.

Both projects will bring hundreds of oil and gas workers into the lands of uncontacted tribes, introducing the risk of deadly diseases and violent encounters, and scaring away the animals the Indians hunt for their survival.

Survival has launched an urgent petition to the Brazilian and Peruvian governments to protect the land of uncontacted Indians, and called on the authorities to honor their commitments of cross-border cooperation.

Survival’s Director Stephen Corry said, “This news could hardly be more worrying – not only have these people confirmed they suffered violent attacks from outsiders in Peru, but they have apparently already caught flu. The nightmare scenario is that they return to their former villages carrying flu with them. It’s a real test of Brazil’s ability to protect these vulnerable groups. Unless a proper and sustained medical program is immediately put in place, the result could be a humanitarian catastrophe.”