by Sarah Pike, Cross Posted from Aeon Magazine

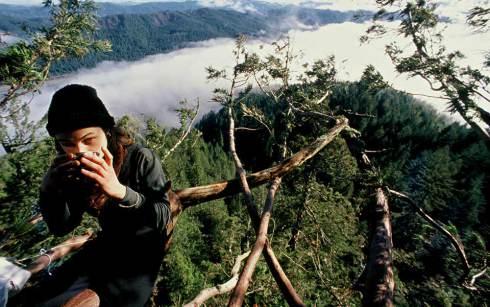

Julia Butterfly Hill spent 738 days living in a 55m California Redwood tree in a successful attempt to prevent the clearing of surrounding forest. Photo by Eric Slomanson

One day last summer, a young woman looked down on a small crowd of vocal supporters and police officers from her hammock or ‘sky pod’, 60ft above an old logging road in Moshannon State Forest in Pennsylvania. The pod was tied to trees and anchored to a blockade across the road, so that anyone trying to move the blockade would release her in a dangerous, perhaps fatal, fall to the forest floor. Another activist on the ground had locked his neck to one of the lines anchoring her pod.

It was a familiar sight from protests against the logging of old-growth forests, but here the target was different. Workers who arrived for their shift that Sunday morning could not get past the blockades to attend to a 70ft hydraulic fracturing drill rig used to extract natural gas from the rock formations beneath the forest floor. ‘You’re adults, but you’re acting like children,’ shouted one of the officers. They had been called to the scene by EQT, the natural gas company that had leased mineral rights to the gas-rich Marcellus Shale that lies beneath a large portion of several northeastern states, including Pennsylvania, Ohio and New York. ‘We are peaceful protesters,’ responded one of the activists. Other officers stood by with assault rifles, waiting to see what would happen.

Later that day, a basket crane removed two tree sitters from the blockade, and three people were arrested for disorderly conduct. Nearly 100 protesters and supporters associated with the 33-year-old radical environmentalist group Earth First! shut down the drilling site for 12 hours. According to Earth First!’s website, this was the first shutdown of an active hydrofracking site in the United States. With the rise of fracking, protest techniques that were developed in the endangered redwood groves and old-growth forests of the west coast of the US have been brought to the heart of the continent. As with their opposition to the logging of old-growth forests, radical environmentalists here put their lives — and their bodies — in the line of fire in order to protect the well-being of forests and waterways.

Law enforcement agencies, news media, local communities and other environmentalists in the US have mixed reactions to acts of civil disobedience and sabotage. The government’s Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) has made radical environmentalists a priority: putting them under surveillance and sending undercover agents to disrupt activist communities. In 2005, John Lewis, an FBI deputy assistant director and top official in charge of domestic terrorism, declared to CNN news that ‘The number-one domestic terrorism threat is the eco-terrorism, animal-rights movement.’ In the past 10 years, environmental and animal rights activists have been aggressively pursued by the FBI, according to the Washington journalist Will Potter in his book Green Is the New Red (2011).

The personal consequences for activists can be devastating. Jeff ‘Free’ Luers, a renowned eco-activist, was a Pagan teenager who talked to trees. When hanging around with his Pagan friends, he recalls: ‘We saw the underlying spirit in things. I became very in tune with the energy around me … the hardest part about being a Pagan is overcoming all you have been taught. I mean, people think I’m crazy when I say I can talk to some trees … And yet it is totally acceptable to talk and pray to a totally invisible god.’

Luers’s early relationships with trees helped draw him into protests against logging, excessive consumption and global warming. At the height of his activism, in the early morning hours of 16 June 2000, Luers and his friend, Craig ‘Critter’ Marshall, crept up to a car dealership in Eugene, Oregon. After checking to make sure no people were in the area, they started a fire that inflicted $40,000-worth of damage to three Chevrolet SUVs. Later that morning, they were arrested. Luers was convicted of 11 felony counts, which included arson and attempted arson, and was sentenced to 22 years and eight months in prison. After much legal wrangling, his sentence was overturned, reduced to 10 years. He was released in 2010, with his idealism remarkably intact.

If government agencies regard eco-activists as a dangerous threat to business and social order, supporters praise them as warriors and heroes who are risking their lives or serving prison sentences for a just and noble cause. Radical activists believe they are freedom fighters at the forefront of a revolution in the relationship between human beings and other species, bestowing on trees and non-human animals the kind of inherent rights usually reserved for humans. Eco-activists tend to reverse accepted definitions of violence. They see property destruction as an act of love, and socially accepted activities such as building a ski resort or selling cars as violent acts against nature. I have been talking and corresponding with eco-activists over the past five years in order to better understand what motivates them.

In a letter written to me from prison, Rod Coronado, a well-known Native American eco-activist who served eight months in jail for sabotaging a mountain lion hunt, conveys his sense of loss:

I’ve seen some of the last great whales slaughtered in Iceland, herds of pilot whales butchered … Old-growth forests being chainsawed, even though there are less than five per cent left, pretty much the worst crimes of violence against nature I have witnessed. I have acted out of rage, sorrow and love, I have held signs, written letters, signed petitions, sabotaged machinery, even burned down buildings.

Out of rage and sorrow, desperation and urgency, environmentalists choose direct action, sometimes crossing the line to sabotage heavy machinery or set fire to buildings that symbolise for them global warming, pollution, habitat destruction, and mass extinction.

Those outside eco-activist communities, such as the police officers called to the anti-fracking demonstration in Pennsylvania, cannot fathom why anyone would risk injury or death for such a cause. Plenty of Americans believe nature is worth preserving, but not at the expense of human interests. But some young Americans — and most direct-action activists are young — continue to join radical environmental groups and participate in acts of civil disobedience, even at the risk of long prison sentences for actions that include sabotage. Why do these activists feel compelled to commit dangerous and often illegal actions at such risk? How do such extreme commitments come about?

Although Luers has been depicted as an ‘eco-terrorist leader’ in the news media and was put on special watch in prison for being politically dangerous, in a statement read at his sentencing in 2001, he insisted that his actions were not violent but were born out of love: ‘It cannot be said that I’m unfeeling or uncaring. My heart is filled with love and compassion. I fight to protect life, all life, not to take it.’

Luers’s determination to ‘fight to protect life’ dates back to an earlier experience. In 1998, at the age of 19, he traveled to the Willamette National Forest in Oregon to participate in a campaign to save an old-growth forest of Douglas fir, Western hemlock, and red cedar. For him, these trees were sacred and divine. ‘Standing before them is a humbling experience,’ he explained, ‘like standing before a god or goddess.’

In ‘How I Became an Eco-Warrior’, written from prison in 2003, he describes joining the Willamette Forest tree-sit. He climbed into a tree he called ‘Happy’ and watched helplessly as nearby trees fell, while activists tried to save the ones they could and delay the loggers’ progress. He recalls sitting back against the tree and meditating:

I felt the roots of Happy like they were my own. I breathed the air like it was a part of me. I felt connected to everything around me. I reached out to Momma Earth and I felt her take my hand … I asked Her what it felt like to have humanity forget so much, and attack her every day like a cancer.

At that moment, Luers began sweating profusely as the boundary between his body and the tree’s body dissolved, and the Earth’s grief became his grief:

I felt the most severe pain all over, spasms wracked my body. Tears ran down my face. I could feel every factory dumping toxins into the air, water, and land. I could feel every strip-mine, every clear-cut, every toxic dump and nuclear waste site.

This experience marked his conversion to radical activism:

The feeling only lasted a second, but it will stay with me for the rest of my life. My life changed that day. I made a vow to give my life to the struggle for freedom and liberation, for all life, human, animal, and earth.

It is common for eco-activists to personify plants and animals as brothers and sisters, and mourn fallen trees as beloved family members. They exemplify a love for other species that the American biologist Edward O Wilson has called ‘biophilia’, an idea popularised in his 1984 book of the same name and described as an innate ‘urge to affiliate with other forms of life’. The anthropologist Kay Milton, professor at Queen’s University, Belfast, studies the ecology of emotions and argues that naming trees and animals is a way to personify nature, invoking an impulse to protect those special beings. Some individual trees have become almost as famous as their protectors: Julia Butterfly Hill became a media sensation and eco-heroine when she spent two years between 1997 and 1999 on a platform in a 1,500-year-old redwood tree named Luna 180ft above the floor of the Headwaters Forest in northern California. As trees fell around Luna, Hill — like Luers — felt the destruction in her own body. In an essay entitled ‘Committed Love in Action’ (2002), she wrote:

Each time a chain saw cut through those trees, I felt it cut through me as well. It was like watching my family being killed. And just as we lose a part of ourselves with the passing of a family member or friends, so did I lose a part of myself with each fallen tree.

When news outlets circulated images of Hill hugging Luna, the tree that was otherwise anonymous in a distant forest appeared in a shared, public space as a person with rights and feelings

When activists empathise with other species, they experience what the American biologist Donna Haraway has described as the bond of ‘companion species’. In her book When Species Meet (2008), Haraway quotes the anthropologist Anna Tsing, challenging us to re-evaluate our relationships with other beings, whether dogs or mushrooms: ‘Human nature is an interspecies relationship,’ she insists, because life consists of ‘knots’ of species ‘co-shaping each other’. Activists such as Hill who sleep and dream in trees for long periods of time without coming down, ‘sharing cells’ as Haraway describes it, discover that their lives are inextricably connected with the lives of other organisms.

For some activists, this sense of intimacy and reciprocity becomes a growing awareness of a sacred presence in nature. Although activists from Christian, Jewish and other religious backgrounds participate in protests too, most US activists have rejected organised religion, or follow Pagan, Native American and other ‘Earth-centred’ traditions. They see monotheistic traditions as separating humans from nature, echoing the famous critique by the American historian Lynn White Jr, ‘The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis’ (1967), in which he blames Christianity and its influence on Western science for our assumption of dominion over other species.

Activists reject the Christian belief of their parents that the divine is outside the natural world, and instead locate it within the world. Christopher ‘Dirt’ McIntosh, who set fire to a McDonald’s restaurant in Seattle in 2003 on behalf of extremist environmental groups, for which he was sentenced to eight years in prison, described to me the awe he felt towards the world as a divine body during the many days he spent outdoors as a child and teenager. He explicitly distances himself from ‘the Jews, Muslims, Christians [who] see their God as an entity upon some throne in the heavens, instead I see the Earth Mother in all things … Her “Body” making up everything in this infinite universe … so the only real law I follow is treating all things natural [as] sacred.’ While in prison, it appears that McIntosh disavowed his commitment to the radical environmentalist movement, yet he continues to stand by his early connection to Earth’s body.

Influenced by the work of the Swiss developmental psychologist Jean Piaget in the 1920s, we might expect the kind of animistic thinking that characterises the childhood stories of activists and their ongoing personifications of nature in adulthood to give way to a ‘mature’ view of a disenchanted world. Piaget borrowed the concept of animism from the English anthropologist Edward Burnett Tylor, who developed the late-19th-century cultural theory about the origin of religion, in which animism is seen as a primitive stage of human development.

But Pagan teenagers such as Luers and McIntosh who carried their love of the Earth and trees as sacred beings into their actions in later years, reject this theory. As McIntosh sees it, most of his peers became increasingly disconnected from nature as they grew up:

their connections to the world of ‘magic’ sever little by little — they may and do encounter nature, but they don’t any longer feel interconnected with it and it becomes abstract to them and their alienation keeps them from seeing it all as they did when they were children.

Although much critiqued and debated, Piaget’s and related views still have a hold over many of us, views that were clearly expressed by the officer who scolded activists for ‘acting like children’. Perhaps they are, indeed, acting like children — children, that is, who have not lost a precious connection to nature.

When eco-activists climb into platforms hundreds of feet up in redwood canopies and occupy fracking sites, they draw on memories of childhood places and experiences, as well as on skills and strategies learnt in action camps and workshops. Ritualised actions such as creating sacred spaces at forest action camps, sitting in trees with nooses around their necks, and chaining themselves to blockades to prevent logging, shape and reinforce these activists’ memories of past relationships to nature.

Childhood memories are bittersweet for many activists: on the one hand they remember nature as a special place that they explored and in which they developed close relationships to trees or animals. On the other, many recall the disturbed places of childhood memory. The first relationship is one of love and attachment, the second of grief and loss. If a child’s sense of self is extended into a landscape made sacred, then the loss of that landscape or its radical transformation into a clear-cut slope or a parking lot is a cause for grief. If particular trees in the landscape have been named, have become friends, then the loss is even greater.

When activists explain what drove them to break the law, they often describe the destruction of remembered places or their shock at seeing a housing development where there was once a field. In 2006 a jury in New Jersey found Joshua Harper and six others guilty of using their website to incite attacks on those who did business with Huntington Life Sciences, Europe’s largest animal-testing lab in Cambridge, UK. Harper was sentenced to three years for ‘conspiracy to violate the Animal Enterprise Protection Act’ for his role in the international animal rights organisation SHAC (Stop Huntington Animal Cruelty). Harper told me that when he was nine, his family moved from San Diego, California to Eugene, Oregon. He explained:

Seeing the juxtaposition between a sprawling hideous southern California city and a small tree-filled Oregon city was shocking to me… As I got older some of the places I had fallen in love with began getting paved over, clear-cut, or polluted. That was all the motivation I needed to adopt a militant outlook on the need for wilderness defence or more appropriately, offense.

Harper’s experience of seeing the landscapes of childhood — which once centred and gave meaning to his world — violated by development is a common theme in radical environmentalists’ accounts of their conversion to activism. Maia Oldham, who became involved with Earth First! after graduating from high school, recalls a similar childhood experience of familiar nature destroyed. She explained to me that she grew up in a small town in southern California where she spent most of her free time making water holes for animals in the desert. During high school, Oldham became troubled by what she saw happening: more and more tract homes being built in the open spaces she had loved as a child, and where she had called wild animals her friends. So one night while she was still in school, Oldham and her boyfriend crept into a construction site for new homes. The teen saboteurs pulled up survey stakes and put corn syrup into the gas tanks of bulldozers on the site, in order to delay the destruction.

Beloved landscapes and memories are ever-present in the stories activists tell about how they converted to environmentalism. In these accounts, the activists imagine both rupture and continuity with the past. Psychologists such as the Harvard professor Daniel Schacter have shown that memories are not a video replay of the past, but shaped by the contours of the present context in which we are doing the remembering. Tree-sits and action camps in the woods, during which activists touch tree bark for hours, sleep under the stars, and listen to the winged creatures and mammals of the forest conjure up particular images and relationships from the past. This past becomes alive with the memories of other times when the smell and feel of trees and earth were vivid and valuable to the remembered childhood self. At protests, this remembered eco-child from the activists’ pasts is invited to participate in the present. At the same time, the present illuminates the past in particular ways, shining light on those scenes in which the ecological child is front and center.

In activists’ accounts of their childhoods, the child’s emerging sense of self is shaped by relationships with other species. The American poet Gary Snyder observes in his book of essays, The Practice of the Wild (1990), that: ‘The childhood landscape is learned on foot, and a map is inscribed in the mind — trails and pathways and groves — going out farther and wider.’ So the activists’ maps of the world, extending out from the self, are not just human-centred, although human friends and family can also feature. Rod Coronado traces the roots of his activism to camping and fishing trips with his family that took him far away from the Californian suburbs of San Jose where he grew up. According to his biographer, Dean Kuipers, childhood trips to the woods moulded Coronado’s ‘lifelong identification of self with nature’. Children actively shape the landscape as they become intimate with it, modelling reciprocal relationships they will revisit later in their lives.

A week before the anti-fracking protest, I was driving down meandering roads in northeastern Pennsylvania, where depressed rural communities are divided over how to respond to the economic opportunities that they believe fracking might bring them. In these struggling communities, concerns about watershed pollution and suspicion of outside corporations sit uncomfortably with the desire for economic self-sufficiency.

‘Home’ read the banner that greeted me at the entrance to Earth First!’s Round River Rendezvous, a weeklong gathering of activists at a hard-to-find site deep in the Allegheny National Forest, 140 miles northeast of Pittsburgh. As I joined activists from around the US sharing strategies, learning climbing techniques and studying legal advice, it became clear that their notion of ‘home’ included the forest and its creatures, as well as the community of like-minded others sharing the site with them. Workshops on a wide range of topics at the Rendezvous showed a multipronged concern with injustice and violence: ‘Fighting Male Supremacy’, ‘Female-Identified, Queer and Trans Listening Circles’, ‘Challenging Racism in Our Movements’, ‘Edible Plants’, ‘Medical Misogyny in the Catholic Church’, ‘Mountaintop Removal’.

Over the course of the week in the forest, activists created a summer camp atmosphere with winding paths through the woods, colourful banners draped over their tents, songs and music around campfires. The primitive, makeshift gathering site with its carefully planned temporary latrines, ropes strung in the branches for a climbing area and community kitchen lent an aura of playfulness to the serious business of organising the anti-fracking protest. Tree-climbing, a puppet show, a talent show and other activities were a constant reminder of the strange juxtaposition of scenes from a childhood campout and such disturbing adult topics as rape and ecological destruction.

As the Rendezvous drew to a close, and a caravan of cars drove slowly away from our temporary home in the forest towards the anti-fracking protest, I thought of the irony of the young activists’ lives. They travel from one protest to another, leading a homeless existence in constant tension with the deep emotional connections to place of their childhood memories, only to re-create the intimacy, for a time, at the Rendezvous. For them, this temporary home was a utopian vision of a future that we are far from achieving any time soon, a vision fueled by their sense of loss and grief. But tree-sits and other forms of eco-activism ask us to take seriously this vision of a world that childhood memory offers us, a world in which humans and other species might live at home together, united by a sense of kinship and community.