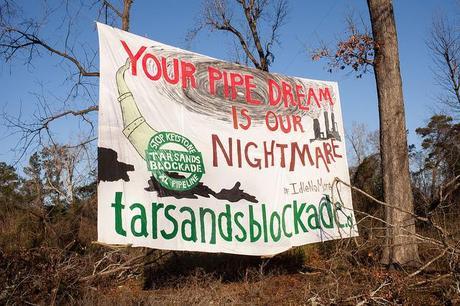

from Tar Sands Blockade

Communities on the frontlines of the tar sands refining complexes in Houston’s toxic east end and Ponca City, Oklahoma near KXL South’s origin in Cushing, are facing increased toxic emissions from the facilities as tar sands transport capacity increases with KXL South. Yudith Nieto, an organizer with Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services (TEJAS), suggests her neighbors in Houston’s Manchester neighborhood have felt sidelined as the national debate about the pipeline remained transfixed on private property scandals and climate change without much regard to the already life-threatening air quality near the tar sands refineries.

“Independent of whether or not KXL South construction went ahead, children in my neighborhood are 56% more likely to contract childhood leukemia than children just 10 miles away,” says Nieto, citing a recent comparative health study of residents living in proximity to refining activity along the heavily polluted Houston Ship Channel. “What we do know is that refining tar sands will only increase that percentage while the refineries keep up their blatant disregard for the lives of those of us forced by circumstance to breathe their dangerous emissions on a daily basis.”

Along the length of the pipeline route, residents nearby are worried by documentation of shoddy construction brought to public knowledge by landowners and advocates. After months of stalling on the part of federal Pipeline and Hazardous Safety Materials Administration (PHMSA) officials, a meeting was arranged in early January to hear concerns about the construction process. During this meeting, PHMSA insisted that TransCanada’s history of shoddy welds, which have lead to catastrophic blowouts, nor the hundreds of photos of damaged KXL South pipe and illegal trenching practices employed during its construction phase gave little reason to not simply have faith that TransCanada had fixed the problems. PHMSA officials also made it clear that they had no authority to ensure TransCanada fully inform community first responders about the chemical makeup of tar sands and what equipment is necessary to ensure effective rapid response.

“PHMSA hasn’t provided one shred of documentation they ever set foot on my land to inspect KXL South construction, and TransCanada’s had absolutely no dialog with our local Fire Chief on preparing first responders,” insists Direct, TX farmer Julia Trigg Crawford, a founding member of Texas Pipeline Watch. “PHMSA and TransCanada may shirk their responsibilities, but our communities step up and proudly take them on. We stand united to do whatever is in our power to protect our families, communities and lands.

Residents in communities along the route are quick to point out that it’s not just landowners who should be concerned. Others living near the pipeline are just as much at risk of toxic exposure should a leak or spill occur. According to them, many who live near the pipeline do not fully understand the ways it threatens their air, water, soil, or health.

East Texas landowner Mike Hathorn’s land is also traversed by KXL South. “No one is ready for it. Most people near me don’t even know what it is,” he explains.

Maya Lemon, of Nacogdoches County Stop Tar Sands Oil Permanently (NacSTOP) shares Crawford’s concerns about emergency preparedness. “In East Texas, first responders will not receive training on responding to a tar sands spill until March 2014, a full three months after the pipeline goes online. If a spill event occurs before then, first responders will not have the information to fully protect themselves from toxic exposure or to ensure the safety of their communities, and should one not occur until after, there’s no guarantee that the training they will receive will be adequate. In fact, there is no way to clean up a tar sands spill.”

Kathy DaSilva with the Safe Community Alliance, also of Nacogdoches, was present at the PHMSA meeting with Crawford. “TransCanada and KXL South’s lead construction contractor Michels were out all last spring digging up hundreds of sections of pipe damaged in the shoddy construction phase of the project. Along the entire length of the pipeline, we documented evidence of outstandingly poor construction practices that are likely actually illegal under PHMSA code, but with no PHMSA inspection officials ever present to the best of our knowledge, the fox was guarding the hen house.”

“I don’t think about my land as much as the entire pipeline. I worry about the whole surrounding area, and I just don’t think it’s good,” adds Hathorn. “As far as our land is concerned, a spill could happen here, it could happen anywhere. And it’d definitely affect everybody at that point.”

Tar sands, a mixture of sand, petroleum, and mineral salts, must be diluted with a highly toxic class of chemical, which industry considers proprietary despite the dangers associated with its use. Tar sands are known to sink in water, making cleanup exorbitantly expensive and practically impossible. When exposed to air, its diluents evaporate like paint thinner forming heavy toxic clouds near at ground level. Toxic chemical exposure through respiration has happened in every instance of tar sands leaking near populated areas, and poisoned residents have described a litany of painful rashes, breathing complications, chemical sensitivities, nausea, migraines, and exacerbated cancer activity.

“Do TransCanada not care for their children or grandchildren?” muses Henrietta Stands-Nelson, an Idle No More Central Oklahoma organizer from Oklahoma City. “They only think of themselves at the moment, and this is why they are known as greedy. I would sure hate for their children to know what their ancestors did for them. Just because you can feed your family off the fossil fuel industry’s fodder doesn’t mean that you should not think of the future. We will need clean food, water, and shelter for ever.”

The tar sands being transported by KXL South originate from a bitumen deposit roughly the size of Florida in Alberta, Canada. The nearby Beaver Lake Cree and Athabasca Chipewyan First Nations are currently in litigation with the Canadian federal and provincial governments to not only halt expansion of the mine sites but to revisit the original permitting of the sites altogether, due to egregious violations of Treaties 6 and 8, to which these First Nations are signatories, respectively. The mine sites, the tribal governments assert, have heavily contaminated their traditional subsistence hunting grounds, devastating local game populations, interrupting cultural continuity, and impeding their national sovereignty.

“We hope from this point on that unity is the clarion calling for the climate movement. It’s really unfortunate for everybody that a lack of solidarity in movement mobilization with Texas and Oklahoma communities has led us to this moment,” laments Juan Parras, the founder of TEJAS.

“As tar sands begin to flow through the pipeline, we recommit to raising our voices to assert our profound dissatisfaction with the process that has allowed this pipeline to be approved, constructed, and put into operation with such cavalier disregard for community health and safety. Environmental Justice communities, residents living in proximity to the pipeline, and all those up and downstream – we’re are all connected here in the same struggle: to permanently stop the most ecologically devastating mining operations in the world and address the ongoing injustices of petrochemical refining. The Keystone XL tar sands pipeline has only catalyzed our resolve to know each other better.”