Sabalites in the hallway to the University of Wyoming Geology Museum.

We tree-followers have gathered once again to report on the status of our trees, the ones we’ve chosen for the year. Mine is a Sabalites palm tree that grew in southwest Wyoming 50 million years ago, and then went extinct. It must have been common around ancient Fossil Lake, and fairly close to shore, because many intact frond fossils have been found in lake sediments now turned to rock—the Green River Formation.I won’t visit Sabalites in its native habitat until it's warm enough for an outdoor vacation, and our local Sabalites, on display in the Geology Museum, doesn’t change from month to month. So what to report? Sometimes tree-followers write about wildlife seen on or near their trees; this month I’ll do the same.

Knightia and Sabalites. Courtesy CSMS Geology Post.

My wildlife sighting was a school of Knightia, small herring-like fish. They were swimming around a large Sabalites frond that was floating in warm subtropical water near the lushly-vegetated shore of Fossil Lake. But wait … there’s something wrong with this idyllic scene. The fish weren’t swimming … they were dead!

Mass mortality slab, University of Wyoming Geology Museum.

How ironic that mass die-off was preserved in exquisite life-like detail! (NPS photo; click to view).

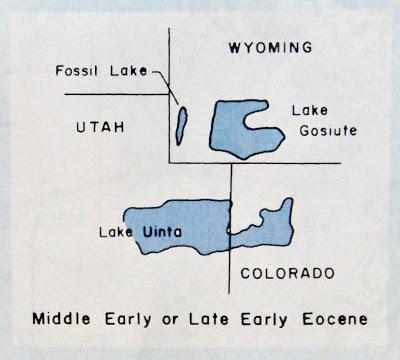

Fossil Lake occupied the southwest corner of Wyoming early in the Eocene Epoch.

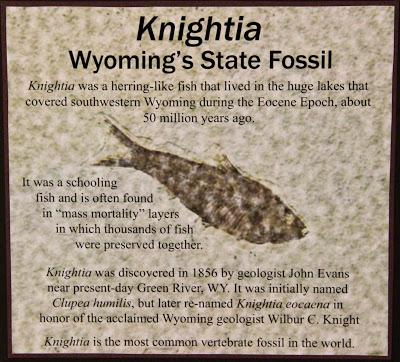

Fossil Lake was the smallest of the large Eocene lakes of southwest Wyoming and adjacent states, yet it’s exceptional in terms of the number of Knightia fossils it left behind. In some “death layers” there are 100+ per square meter—over an area of tens of thousands of square meters! Millions of Knightia fossils have been excavated—it’s the most common fish fossil in the world! In 1987, it was designated the state fossil of Wyoming.

Most common vertebrate fossil or fish fossil? Both claims are out there.

The Fossil Butte Member of the Green River Formation includes many mass-mortality layers, representing multiple events scattered across thousands of years. Apparently die-offs were not rare catastrophes, but something that occasionally happened under specific conditions. But those conditions remain a mystery. Maybe fish were poisoned by cyanobacteria, or suffocated by super-blooms of algae, or killed by changes in water temperature or chemistry or both. Maybe Knightia was especially susceptible. Its modern-day relatives, the herring, are known to die off en masse in response to sudden environmental change. Fortunately herring recover quickly—one fish can lay 200,000 eggs at a shot! Maybe Knightia was equally fecund.Knightia had more than environmental change to worry about. Given its abundance, it probably was the main food for predator fish, like Diplomystus dentatus below. This fossil is not from a mass mortality bed, so what killed it? “It most likely died from starvation or suffocation because it could not spit the Knightia out” (NPS).

Did Diplomystus' dinner do him in? (NPS photo; click to view the remarkable preservation).