On a hot afternoon several weeks ago, I pulled into Hittle Bottom Campground on the Colorado River in southern Utah. After parking in the only site with shade, I opened the windows, put screens in place, inserted $10 in the payment envelope, and started for the pay station. But I was stopped in my tracks by a Killer Tree, right next to our campsite!

On a hot afternoon several weeks ago, I pulled into Hittle Bottom Campground on the Colorado River in southern Utah. After parking in the only site with shade, I opened the windows, put screens in place, inserted $10 in the payment envelope, and started for the pay station. But I was stopped in my tracks by a Killer Tree, right next to our campsite!The area around it had been cordoned off with orange caution tape, but I checked carefully to make sure we were safe. Indeed everything was fine. We were out of range of falling limbs.

Click on image to view caution tape, marked by arrows.

The big cottonwoods that grow along lowland rivers in North America—Populus deltoides and P. fremontii —are infamous for dropping large dead branches. As the Colorado AAA has observed:No one writes poems about “under the spreading cottonwood tree” because it can actually be dangerous to sit under a cottonwood in high winds due to breaking branches.

The technical term for this is "dieback".

Some cities (Denver for example) ban these cottonwoods in part because of dieback. They grow fast (to six feet per year!) and are relatively short-lived, so falling limbs will be a problem. And they grow roots toward and into reliable water sources such as city water and sewer lines! This is an impressive adaptation for the trees but a problem for us (source).

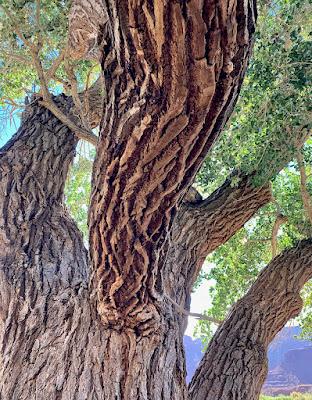

The Hittle Bottom Campground has no water aside from the river, so managers don't worry about cottonwood roots invading plumbing. But dieback is a problem, hence the caution tape. Of course I wanted photos, so I risked my life so in the absence of imminent danger (the day was calm) I stepped over the tape to commune with the Killer Tree.

Zig-zag form due to lost branches.

The bark was especially photogenic, even with caution tape.

This is Fremont's Cottonwood, named to honor the famous explorer and surveyor John Charles Fremont. However the honor probably celebrates another of his achievements, one much less widely known—botanical discovery! Fremont was not a taxonomic expert but he knew how to collect plants. And collect he did—on the order of two thousand specimens. Among these were at least 165 species new to science, some 40 of which were named in his honor. For more about Fremont's botanizing, see JC Fremont was here.

This is Fremont's Cottonwood, named to honor the famous explorer and surveyor John Charles Fremont. However the honor probably celebrates another of his achievements, one much less widely known—botanical discovery! Fremont was not a taxonomic expert but he knew how to collect plants. And collect he did—on the order of two thousand specimens. Among these were at least 165 species new to science, some 40 of which were named in his honor. For more about Fremont's botanizing, see JC Fremont was here.On the afternoon of March 30, 1846, Fremont and his party "encamped on Deer Creek, another of these beautiful tributaries to the Sacramento [River, in California]. Mr. Lassen, a native of Germany, has established a rancho here ...". They stayed for five days, during which time Fremont collected plants, including a cottonwood. He suspected it might be a new species, as he noted the previous year when he was in southern Utah (no collection was made or survived).

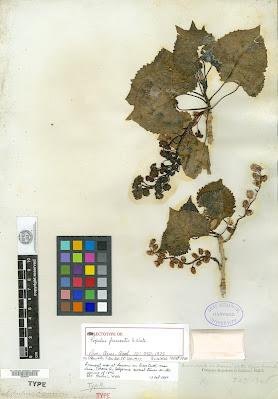

Fremont's 1846 specimen from "Deer Creek at Lassens" (Gray Herbarium). He collected both male (above) and female (below) flowers, demonstrating knowledge and care in collecting plants.

Typical of field botanists at that time, Fremont relied on experts for identification. He sent many of his collections to the leading American plant taxonomist—Asa Gray at Harvard. Gray often passed along specimens from the western part of the US to his colleague, Sereno Watson, who was more familiar with the region's flora. It was Watson who named and described Populus fremontii.

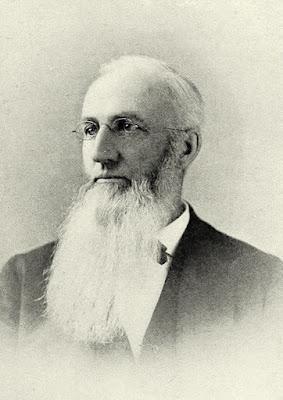

Sereno Watson (Wikimedia). A colleague described him as "tall, very erect, [with] good features, a high-bridged nose, and a carefully tended beard of great length and whiteness. Almost to the end of his life he walked with a brisk elastic step suggesting physical energy remarkable for a man of his years."

In his 1875 paper, Watson distinguished P. fremontii from its close relatives "especially by the remarkably developed torus" (now called floral disc). He also noted that young growth tended to be somewhat hairy. In contrast, the similar P. deltoides has smaller floral discs and young growth is not hairy.A century later, James Eckenwalder, expert on the genus Populus, reached the same conclusions, recognizing the larger floral disc and often hairy young growth as distinguishing features for Fremont's Cottonwood (see also his treatment in Flora of North America).

Populus fremontii from Sargent's 1896 Silva of North America; added enlargement shows female flower with floral disc—thought to have evolved from petals and sepals.

Fremont's Cottonwood with capsules and young leaves (TreeLib, J Morefield photo).

Mature leaves and bark, Fremont's Cottonwood (TreeLib).

These last photos are included in part to thank Blake and Nathan Willson for their wonderful Tree Library website—"a digital platform for teaching and studying trees with a focus on promoting awareness and understanding of trees and their global importance to the environment."

Fremont's Cottonwood, Rio Grande, New Mexico. "Trees are our silent partners, sensing us as we move about, providing shelter, offering us beauty, and nurturing and protecting the earth." (TreeLib)

Sources, in addition to links in post

Eckenwalder, JE. 1977. North American cottonwoods (Populus, Salicaceae) of sections Abaso and Aigeiros. J. Arnold Arboretum 58:193–208 [P. fremontii p. 198-200] BHL.

Fremont, JC. 1887. Memoirs of my life: including in the narrative five journeys of western exploration during the years 1842, 1843-4, 1845-6-7, 1848-9, 1853-4 Internet Archive.

Sargent, CS. 1896. The silva of North America: a description of the trees which grow naturally in North America exclusive of Mexico. Vol. 9 (P. fremontii p.183 ...) BHL.

Watson, S. 1875. Revision of the genus Ceanothus, and descriptions of new plants ... Proceedings American Academy of Arts & Sciences. Vol. 10 (P. fremontii p. 350) BHL.

This is my October contribution to the monthly gathering of Tree Followers, kindly hosted by The Squirrelbasket.

This is my October contribution to the monthly gathering of Tree Followers, kindly hosted by The Squirrelbasket.