West of Eden, Ed: Ian Boal, Janferie Stone, Michael Watts, and Cal Winslow, PM Press, Oakland, CA, 2002.

Roaul Vaneigem, The Revolution of Everyday Life, PM Press 2002.

A Review of Two Books Two Years Later

by Sasha / Earth First! Journal

My charge is to question whether or not we can set forward a “post-Occupy” path of radical organizing. But immediately, we are faced with the problem of time. The world after Occupy looks a lot like the world before Occupy—perhaps angrier, perhaps more intense—but generally, Occupy has been assimilated or diffused. The question of “do we continue Occupy” is less important than, “do we continue the strategies and tactics of occupation/decolonization and resistance?”

I will set out in this essay to review two books that broach the problem of radical movements, insurgencies, and declines—West of Eden and The Revolution of Everyday Life—in the context of the space between today and when they were published. This difficult task is complicated by the fact that both books are retrospective—the former being an edition of essays based on the Communal Movement of the late 1960s and 1970s, and the latter being a compendium of texts including the famous essay “Treatise of Knowledge-Life and the Usage of Young Generations” collected by the Situationist author, Raoul Vaneigem in 1983 and republished also in 2012.

If I have taken two years to review these two books that were sent to me in the year that Occupy still existed, it is because of my own personal transformation that has taken place, partly around these two books, and partly around the aftermath of the repression/implosion of Occupy.

Both books, published by PM Press in 2012, look back to the culture of the 1960s and 1970s—the back to the land movement, the occupation movement of 1968 and Situationism at large. Without formulating rash judgments about these cultures of insurrection and resistance, these two books give us a fresh reminder of avenues or possibilities of the present. They are at times romantic and repugnant, but two years past the end of Occupy, they yield fresh thoughts and insights into the building blocks of that movement and the longer revolution.

Can we say that these movements—Back to the Land and urban aesthetics—have been revived since Occupy? It is an almost unanswerable question; though they may be been building up steam. Even more, perhaps it doesn’t matter. The lesson of these books is that collective action takes place through the agency of the individual, so why worry about how many people are involved? The disillusionment of Occupy has fostered greater hope. Art and spaces of escape (dare I say, “the art of escape”), having become utterly necessary, is taking over. The promise of The Revolution of Everyday Life and West of Eden is not necessarily to revive either tradition, but to revive the life of the mind, that we might continue to be escape artists in the world of catastrophe—that we might shirk our chains, and sustain those elusive communities growing greater by the day.

An escape artist

Escape Art

To quote Vaneigem, “It is my belief, despite all the dillydallying—as the barbarism of old continues, thanks to inertia, to tyrannize over the present—that a new society is being built in secret, that genuinely human relationships are coming into being—without replying to oppressive violence by a like violence (albeit directed at the oppressor)—relationships able to create zones of freedom where existence can free itself from the diktats of the commodity, banishing competition in the name of emulation and work in the name of creativity.” It is clear from the start the profound influence that Vaneigem had on The Coming Insurrection, yet this fact alone already reminds us that Occupy was perhaps a stage, an attempt at something greater, which provides a building block.

The secrecy of the space of escape is its life-breath. Passed on from one to another through signs, gestures, information and knowledge—it could be as simple as an old recipe or the gift of a native plant, whose seeds will be spread to broader communities—is this commonplace, this emulation that shares and builds empowerment. Building or growing the movement becomes as critical as breaking down the structures of repression. But the two must be maintained as different, although they intertwine: the retreat into one without the other leads to empty self-aggrandizement.

The lessons of West of Eden suggest that such a community-building process remains extraordinarily difficult. As Michael William Doyle explains in his essay, the book seeks to “help us rid ourselves of the idea that success or failure can be adequately assessed on the sole basis of how long a commune or collective lasted or how big it was.” The book seeks “not to read happiness back into a past that, when it was being experienced as the present, was fraught with other states of mind and emotion besides bonhomie.” As the communards navigated their lived experience in the context of the Cold War, they left tracks useful to us emerging in the contemporary setting—the tipping points of climate change setting the stage of interimperialist rivalries that threaten global war on an unimaginable scale.

But does all of this mean that we, today, are failing? No! Such an analysis is equivalent to the injunction mentioned by Vaneigem: “Become as insensitive (and hence as easy to handle) as a brick! That is what the social order benevolently asks everyone to do.” Against this cynicism, Vaneigem proposes, “It seems better in the end to go straight to a radical and tactically worked-out rejection rather than knock politely on every door looking to swap one kind of survival for another.” Here, Vaneigem notes that the problem of “neutral relations” presented by the frustrations of everyday life as “a cog in the machinery that destroys people” produces the reality of violence out of boredom—such is the stuff of mass killings, as was seen recently through the motifs of white supremacist, patriarchal animosity produced by so-called “Men’s Rights.”

Albion communard plays guitar at rally (circa 2001, courtesy of EF! Journal archive)

Overcoming Reaction

Almost as a rejoinder to the scholar Walter Benjamin’s noteworthy maxim, “there are no meaningfully political goals,” Vaneigem insists, “The desire to live is a political decision.” Here, the communards of the Back to the Land movement recall a “revivif[ied] variety, nuance, vitality, and diversity of communal life,” where “[r]ural farmers deeply enriched the skills and knowledge of communards, as communes relied heavily upon elder knowledge of animal husbandry, blacksmithing, manure composting, wood milling, maple sugar boiling, and other traditional rural craft.” We respond with the urge mounting to build and rebuild something new out of bioregional praxis.

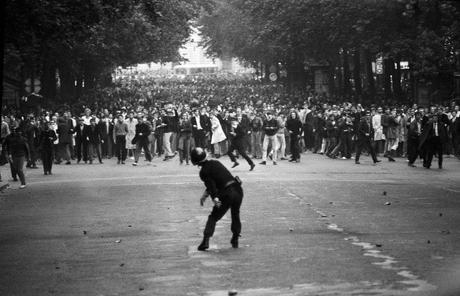

Yet this urge takes a crucial fork in today’s “post-Occupy” world—the world of unforgiving annihilation that has possibly even forgotten the name Occupy. With the Left significantly weakened, the Right has taken up the banner of anti-austerity and land defense, garnering crucial electoral victories throughout the EU (and, we might predict, in coming elections throughout the US). Recognizing that neither May 68 nor the Back to the Land movement was either rural or urban, but united by a common cause of liberation, is the first step towards reconciling the two traditions against reactionary, right wing revanchism.

West of Eden bears testimony to collective liberation with essays on the American Indian Movement’s occupation of Alcatraz and the Black Panther Party’s extensive network of houses and offices throughout the San Francisco Bay area. “The Black Power movement included politics that were personal, experimental, transformative, and rooted in the bold redefinition of self and community,” declares Robyn C. Spencer in her essay on feminist insurgency within the Black Panther Party. Such a process entails the recognition of “many small activisms” for American Indian Movement scholar Janferie Stone in her article in West of Eden. Yet other essays in the collection reveal how some “small activisms” merely set the way to serving Power, often by adapting revolutionary forms to traditional patriarchy.

As an antidote, Vaneigem’s admonition becomes all the more important: while there are many activisms, “There is only one way to be radical.” Through all the different engagements with truth and theory, there remains a steadfast “long revolution” encompassing the projects of decolonization and liberation in the lasting project of solidarity. For Vaneigem, the movement away from the “developed” idea of industrial labor, towards community with Indigenous peoples, involves “the importance of play and creativity.” If the mainstream has forgotten about Occupy, it is because it has been pushed further to the brink of image-shattering liberation.

Paris, May 1968

Liberation from Despair

At every turn, West of Eden and The Revolution of Everyday Life look to move beyond despair—even if that means taking the most realistic perspective, however forbidding. “[D]espair of consciousness makes murderers in the name of order,” declares Vaneigem, “the consciousness of despair makes murderers in the name of disorder… The crypt of despair resounds with the croaking call of counterrevolution.” The clarity of Vaneigem’s clarion call is rendered in stark relief: “death against Power or death in Power’s bosom.” The response of both works poses a challenge: to throw oneself into life without fear, to follow one’s joy and abandon the resentments that constrain us in the past—hence, Vaneigem’s “wild urge to live” moves towards “debating, singing, drinking, dancing, making love, taking to the streets, picking up weapons, and inventing a new poetry.”

What emerges out of both books is a yearning for a pleasurable life, a resistance and aesthetics of pleasure. “How blissful,” asks Vaneigem, “is the forest of radical subjectivity?” The point of intervention that stops the systemic violence of the order of everyday life under capitalism begins at the intervention of subjectivity—the moment where the individual breaks away from that which creates them, and strives to make themselves, in accordance to the liberation of the world around them, into a place of delight and creativity. “If the ancient cry ‘Death to the Exploiters’ no longer echoes through the streets, it is because it has given way to another cry, one harking back to childhood and issuing from a passion which, though more serene, is no less tenacious. That cry is ‘Life First!’”

To this, of course, we add “Earth First!,” because Earth is the living entity that gives value to our lives, and without that from which we come, we are nothing but an idea, a memory constrained to artifacts. As West of Eden shows, the “end” of the communal movement was more than an “end.” With the careful inclusion of a photograph from a 1980s blockade of a logging road in Central California, the editors hint to the spontaneous uprising of Earth First! out of the land-based tradition, beyond the communes of Albion.

Albion blockade, “Stumps Suck!”

What both books acknowledge, however, is how the libidinal economy of pleasure escapes control and evades revolutionary logic. For Vaneigem’s part, the disaster of the capitalist expropriation of desire after 1968 is palpable; in West of Eden, the immediate problems of patriarchy and sexual abuse are examined as crises that plagued the Communal Movement all too often. Of course, no social movement worth its salt can exist without confronting dilemmas of patriarchy, racism, and settler consciousness, and EF! is no stranger to these confrontations. As long as the movement continues down the road to liberation, we will continue to smash patriarchy.

As we return to the land, and the spirit of liberation which pervades both West of Eden and The Revolution of Everyday Life, we recognize that we are in this fight together. To make common cause is to listen to one another, to reflect on lived experience, and to appreciate that concatenation of pleasure that erupts into riots, revolutions, and love; that which declines and that which rises up.

Check out Sasha’s new anthology, Grabbing Back: Essays Against the Global Land Grab, Oakland, (AK Press: 2014) with essays by Noam Chomsky, Dr. Vandana Shiva, Mountain Justice folks, Rising Tide peeps, and more.