Beautiful and complex geology.

But first ... the simple part.

To travel back in time through the Owl Creek Mountains south of Thermopolis, start at the “Wedding of the Waters” (above)—not a confluence but a name change. In the 1800s explorers traveling up the Bighorn River were stopped here by an impassable canyon in a mountain range. To the south, other explorers traveling down the Wind River were stopped by an impassable canyon in a mountain range. Then someone crossed the mountain range and discovered: same canyon, same mountains, same river. But the names were well-established, so the Bighorn and the Wind Rivers were wedded here.

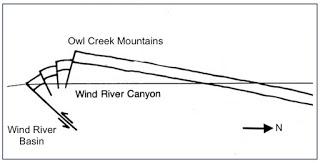

The Wind River flows north through the Owl Creek Mountains. It was superimposed on the range.

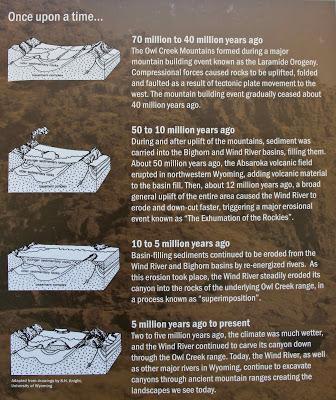

Stream superimposition courtesy Wyoming State Parks. Click on image to read.

The Wind River Canyon is no longer impassable. It's traversed by the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad and US Highway 20, on opposite sides of the river. There are geological “waypoints” along the highway—signs indicating changes in rock layers and time.

Redbeds of the 185-225 million-year-old Triassic Chugwater Formation, says the small brown sign on the right.

This used to be a monotonous landscape (often underwater) underlain by thousands of feet of flat-lying sediments and rock. But then roughly 65 million years ago, during the Laramide Orogeny, the Owl Creek Mountains rose steeply along an east-west thrust (reverse) fault. The range is asymmetric—it dips gently to the north, only about 4-10º.

The Owl Creek Mountains, with a steep south side created by the Owl Creek thrust, and a gently-dipping north flank. Modified from Lageson & Spearing 1991.

The rock layers dip down to the north, so the highway crosses progressively older rocks going south (upstream) through Wind River Canyon.Signs of the times:

The road grade is gentle and rocks dip to the north, so sometimes it feels like you’re going downstream.

Massive Bighorn dolomite and Madison limestone cliffs dominate much of the canyon scenery. The Gallatin is at road level to left (below).

Brown outcrop is Gallatin limestone and sandstone.

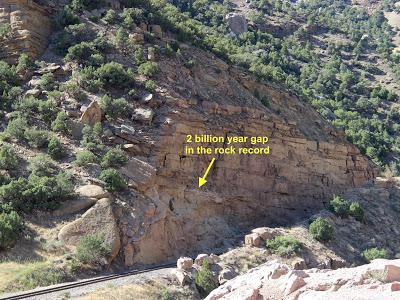

Deep in time and about 13 miles south of Thermopolis, the highway crosses the Great Unconformity, a gap in the rock record of almost two billion years! That’s a huge amount of missing time, nearly half the age of the Earth.

The bus is passing the Great Unconformity on its right.

Near the south end, the canyon narrows and enters dark ancient rocks that are 2.7 to 2.9 billion years old (Archean), the oldest in the canyon. The pink and white veins and blobs are quartz monzonite and pegmatite intrusions.

The dark rocks are hard schists and amphibolites resistant to erosion. The river had to cut a narrow canyon to get through. Both the highway and the railroad pass through tunnels before popping out into the bright sunlight of ... the Wind River Basin? Not yet.

The dark rocks are hard schists and amphibolites resistant to erosion. The river had to cut a narrow canyon to get through. Both the highway and the railroad pass through tunnels before popping out into the bright sunlight of ... the Wind River Basin? Not yet.

Looking back toward the dark canyon and tunnels (halfway along dark rock band). Note displacement between pale rocks on distant horizon and same pale rocks on right.

Beyond the tunnels is an obvious fault where Paleozoic rocks are in contact with (at the same level as) Archean rocks. Is this the steep south flank of the Owl Creek uplift? But if the dark Archean rocks are indeed the hanging wall of the Owl Creek thrust, which lifted the mountains at least 10,000 feet, shouldn’t they be in contact with much younger rocks?Oh dear! The story was so clear and awe-inspiring traveling up the canyon. Some readers may wish to jump to How (and why) to get there below. But maybe look at the pictures en route … it’s great scenery even if we don’t understand it.

Great views of puzzling geology from Boysen State Park campground.

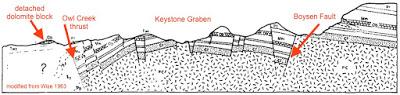

The fault just beyond the mouth of the narrow canyon is a normal fault with about 1500-2000 feet of displacement (Boysen Fault in diagram below). The Owl Creek thrust is further south. The area between the two faults has been interpreted as an arched block, itself fractured into minor horsts and grabens. Huge chunks of limestone and dolomite lie scattered about.

Modified from Wise 1963. Click on image to see details.

The block between the two faults has been called keystone graben (plural; Wise 1963). Blackstone (1988) used “complex faulted arch” and Maughan (1987) called the area the Boysen Area Structural Complex. It is complex!

A normal fault offsets the Cambrian Gallatin Formation – rock band in mid photo (see Lageson & Spearing 1991). View is west from the State Park campground; note railroad tracks.

To make things even more confusing, limestone and dolomite outcrops in the arched block dip in a multitude of directions. Wise (1963) concluded they are detached blocks. The limestone and dolomite strata are brittle, and with faulting they broke into chunks that slid on top of weak Cambrian shales under the influence of gravity. Thus their dips are independent of the horst-and-graben structure of the arch.

Blocks of Paleozoic calcareous rock slid and came to rest atop Triassic strata. View near south margin of the Boysen Area Structural Complex.

Perhaps the most awkward part of the puzzle is thrust and normal faults from the same period of time. The normal faults may have been adjustments to the steep uplift on the south flank, sometimes referred to as “roll-over” (Lageson & Spearing 1991). Wise (1963) attributed multiple fault types to varying responses of multiple rock types:“A fault pattern produced by range uplift in the middle Rocky Mountains can be extremely complex and consist of nearly simultaneous movement of many seemingly mutually exclusive fault types. In detail, however, these faults can be quite rational stress reorientations and yields of rocks of different strengths.”He proposed the following sequence for the “frontal fault zone” of the Owl Creek Mountains (shortened slightly):

1. Initial minor thrusting to the southeast of Ordovician carbonates perpendicular to an incipient northeast-trending fold axis in basement.

2. Broad uplift of the entire range with reverse faulting and some local tight folding along the frontal fault zone.

3. Continued arching in the frontal zone to drop a line of keystone graben along the crests of the major frontal fold in basement. The Boysen fault, largest of the normal faults of this stage, formed early in the sequence …

4. Juxtaposition of suitable weak formations by frontal faults at the lower slopes of the range during stage 2, left long inclines of relatively poorly buttressed massive Paleozoic carbonate formations. During fault adjustments to the keystone graben in the late portions of stage 3 large masses of these carbonates broke loose by normal faulting to ride out as gravity slides …

How (and why) to get there

Wind River Canyon is on US Highway 20 between Shoshoni and Thermopolis, in central Wyoming. It’s impressive and accessible (except sometimes in winter). The drive through the canyon is about 20 miles long.

The Boysen Area Structural Complex starts at the north end of Boysen Reservoir, about 12 miles north of Shoshoni. It may be hard to understand, but the scenery is spectacular and it’s easy to see and appreciate the geological jumble.

Just south (upstream) of the dark narrow canyon, there’s a shady State Park campground with good views of the keystone graben, and new interpretive signs about the area’s geology.

Thermopolis, north of the Wedding of the Waters, features hot springs—including the free State Bath House of Wyoming (how many states have state bath houses?).Sources (in addition to links in post)Blackstone, DL. 1988. Traveler’s guide to the geology of Wyoming, 2nd ed. Geological Survey of Wyoming Bulletin 67.Johannesmeyer, T. 2011. Teachers summer energy education program field guide. Northern Wyoming Community College District. PDF here

Thermopolis, north of the Wedding of the Waters, features hot springs—including the free State Bath House of Wyoming (how many states have state bath houses?).Sources (in addition to links in post)Blackstone, DL. 1988. Traveler’s guide to the geology of Wyoming, 2nd ed. Geological Survey of Wyoming Bulletin 67.Johannesmeyer, T. 2011. Teachers summer energy education program field guide. Northern Wyoming Community College District. PDF hereLageson, DR and Spearing, DR. 1991. Roadside geology of Wyoming, rev. 2nd ed. Missoula: Mountain Press Publishing.

Maughan, EK. 1987. Wind River Canyon in Beus, SS, ed. Rocky Mountain Section of the Geological Society of America: Decade of North American Geology, Centennial Field Guide 2:191-196.

Wise, DU. 1963. Keystone faulting and gravity sliding driven by basement uplift of Owl Creek Mountains, Wyoming. Bull. Am. Assoc. Petroleum Geologists 47:586-598.