Fair Trade and the Maritime Link

Fair Trade and the Maritime Link

by Robert Devet / Halifax Media Co-op

Deborah Stienstra thinks there is something missing in how we talk about the costs and benefits of the Maritime Link.

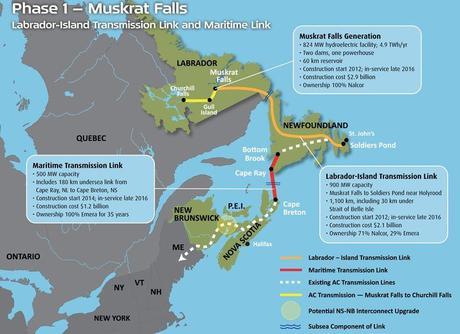

The Maritime Link is shorthand for a mega-project that involves the damming of the Lower Churchill River, the construction of a generating plant at Muskrat Falls in Labrador, and the sub-sea cable and overhead transmission lines necessary to deliver electricity to Nova Scotia and beyond.

“Costs and benefits are different for different groups of people and nobody has been asking about that,” says Stienstra. Stienstra is a professor in Disability Studies from Manitoba who will be holding the Nancy’s Chair position at Mount St. Vincent University for the next two years.

“For instance, there isn’t one universal user of power in Nova Scotia, says Stienstra. “There may be somebody who is on a limited income, she may be a senior, maybe a man or woman with disabilities, she may be aboriginal, they may be children, so there are lots of different users.”

Stienstra is affiliated with FemNorthNet, a network of academics and community-based organizations that looks at how development in Northern communities affects women and how to help those women create change. Change that benefits everybody, regardless of gender.

In a very immediate way the cost of the Maritime Link is an issue for Stienstra. Power rates in Nova Scotia will go up to pay for the Maritime Link, and that is a big problem for people on low income. Stienstra believes those people, many of whom are women, should be exempt from power bill increases.

But the costs of the Maritime Link are more than just financial. There are environmental, social and cultural costs as well.

As an example, the Nunatsiavut government, the regional Inuit government in Labrador, has started monitoring mercury levels in the Churchill River, which are expected to rise as a result of the Muskrat Falls dam construction.

“We’re quite concerned, once the river is dammed, we may not be able to eat the fish, we may not be able to eat the seal, and that will cause a large impact on food security for our people,” Patricia Kemuksigac, Nunatsiavut’s health minister, recently told the CBC.

Also in Labrador the NunaTukavut Community Council, the group that represents Inuit-Metis in Central and Southern Labrador, are very worried that the transmission lines will further negatively affect an already threatened caribou herd. Fundamentally, the conflict is about aboriginal rights and title to the lands.

In April, RCMP arrested eight protesters, including the NunaTukavut Community Council president, during a protest near the Muskrat Falls worksite. The group, subject to a sweeping court injunction, argues that both the injunction and the arrests infringe on their freedom of speech and freedom of assembly.

And then there are the costs to the people who live in Happy Valley-Goose Bay, the small community near Muskrat Falls. Construction of the dam will require 1500 workers, many of those workers will be of the fly in – fly out variety.

“What we know from big developments is that if you bring workers in, there is often an increase in violence against women, an increase in crime and drugs, we’re beginning to see this already in Happy Valley – Goose Bay”, says Stienstra, who raises similar concerns about Point Aconi in Cape Breton where the Maritime Link will come ashore.

What about benefits? Construction brings jobs, after all.

Stienstra is afraid that marginalized groups will not benefit from new job opportunities as much as could have been the case. Looking at Happey Valley-Goose Bay Stienstra points to a lack of childcare support, insufficient training opportunities, and high housing costs as formidable hurdles for women looking for a job. So far she has not seen any indication that job opportunities in Nova Scotia will be any more accessible to marginalized people.

Who will benefit without a doubt are the shareholders of Emera, owner of Nova Scotia Power Inc, says Stienstra. “But I don’t expect that there wil be very many women or folks with disabilities or aboriginal people who are shareholders of Emera.”

Stienstra and others in FemNorthNet intend to do more than just criticize from afar. They have already made their case in front of the Utility and Review Board here in Nova Scotia, and also in Labrador during federal environmental hearings.

But what they really want to do is build a network of affected women in Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador.

We are beginning to understand that if we can create the capacity among women to identify changes and begin to engage in making changes, we are really making a very big change,” says Stienstra. “It is subtle, and it takes a while to happen, but it isn’t a flashpan sort of opposition, it is realy trying to restructure things.”

It’s not easy for anybody to argue against jobs and economic development, let alone if you live in a small community and are part of a marginalized group.

“For some it doesn’t feel safe. The risk is that these small communities get divided, and rather than being seen as supporting economic development they are critics,” says Stienstra.

“So by linking women in Nova Scotia with women in Labrador, we make sure that they don’t feel alone, the’re all dealing with similar things. Because together you have more strength than you do alone.

Stienstra’s group will focus on facilitating this alliance-building effort, inviting people to take part, and raising the public profile of their concerns. As an example, next spring they hope to invite Nova Scotia women who are willing to sustain such a relationship to do a five-day knowledge sharing tour in Labrador.

Why the focus on women?

“What I have learned from the aboriginal women in our group is that women are often the keeper of communities. That is partly because many women’s approaches are relational, and communities are built on relationships and are not about individual gain,” Stienstra believes.

Stienstra argues that the concerns she raises should be part of the Maritime Link discussions in Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland.

“We really need to think about this as fair trade, says Stienstra. The people who are living with the effects are paying the long term environmental, cultural and social cost for cheaper and greener power here.”

“Electricity isn’t neutral, it does’t just come from nowhere. It’s somebody’s land and somebody’s river and somebody’s home, and those somebodies are the ones who will bear the long term burden of this development.”