Ready, set, type! Maksim Kabakou/Shutterstock

Ready, set, type! Maksim Kabakou/Shutterstock

By Sally O’Reilly, The Open University

Lecturer in Creative Writing, The Open University

We live in a culture obsessed with speed: fast-food, Twitter, overnight celebrity, instant make-overs and cutting edge techno-gadgets. We drive too fast, desperate to get ahead literally as well as metaphorically. And when we get home we surf TV, scroll through Facebook, eat, drink and talk on the phone. Apparently, the only thing we want to slow down in the modern world is the aging process – and it’s no surprise that our solution to that problem is a quick injection of Botox or a lunch-time facelift.

Far from being an oasis of tranquillity, the world of books is not immune to the demands of 24/7 society. Publishers – keen to get a new writer’s name on the radar – are at the very least likely to commission a book a year from each author. Some want writers to work even more quickly. Six months is seen by some as a reasonable gestation period for a genre book; three months is not unknown. (Literary writers get more leeway, but the pressures are still there. Prizes must be won; the public must be satisfied.) After all, the aim is to get the book out there, in front of readers, on Amazon.

As for the other writers, with that brilliant, world-changing novel as yet unwritten, the answer is surely to write one as soon as possible. Until the thing exists in tangible form, then the dream of being a writer will never become a reality. One solution is to sign up with NaNoWriMo, a global writing project which takes place every November. Writers log in, pledge to produce 50,000 words by the end of the month – and off they go. Some fall by the wayside, but the organisers report that last year more than 300,000 reached the target: “They started the month as auto mechanics, out-of-work actors, and middle-school English teachers. They walked away novelists.”

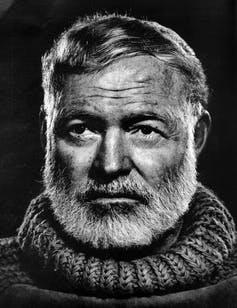

Up to a point. Those NaNoWriMo completers have certainly written enough words to fill a novel – although a fairly short one in contemporary terms – but this is inevitably a process that privileges speed over quality. As Ernest Hemingway observed: “the first draft of everything is shit”. Equally, even if it’s accepted that these 50,000 words form a work in progress, the value of writing that much that quickly is unclear.

My own experience is that writing a first draft without reflection can in itself be a strange form of evasion – you keep writing in the vain hope that by producing lots of words the problems in your narrative will resolve themselves. But sometimes it is essential to stop and think – and question. Before I completed my first novel, I began two other novels that hit the wall at 30,000 words. I fell short of NaNoWriMo’s 50,000 goal, but wrote in that spirit, churning out words against the clock, smoking furiously. (I was young then, and thought this was part of the deal.)

There are pros and cons of writing under pressure. Every writer is different, and this applies to speed of production as much as it does to style. In the “speed” corner we have George Simenon, who would have been a NaNoWriMo natural, with an average novel production time of four weeks; and John Grisham, who wrote his bestseller The Pelican Brief in 100 days. One of the most notorious writers both at and on speed was Jack Kerouac who penned On the Road in three weeks, aided by Benzedrine. The result, produced on a 120-foot scroll manuscript, prompted Truman Capote’s killer put-down: “That’s not writing, it’s typing”.

In the slow corner is Donna Tartt, whose career does not appear to have been damaged by producing a novel every decade. Then there’s Tom Wolfe, who took 11 years to write A Man in Full and J.R.R Tolkien, who began writing what was to be The Lord of the Rings in 1936 and finished in 1952. But the daddy of slow writing must be William H Gass, who took 30 years to write his masterwork, The Tunnel.

I’m not suggesting that one group is superior to the other, but it’s important to remember that along with their unique voice each writer found their natural speed. My last novel took four years to write and that seems to be my optimum pace. Some writers need to take their time. Writing a novel isn’t like going on The X Factor – itself a concept which is looking stale – and though impatience and dissatisfaction can fuel determination, they can also be a snare.

***

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Advertisements &b; &b;