by Hannibal Rhoades / Intercontinental Cry

The ongoing saga around ‘human safaris’ and the closure of the Andaman-Nicobar trunk road has taken new turns in the past few months causing frustration and fostering innovation in the campaign to end this despicable phenomenon.

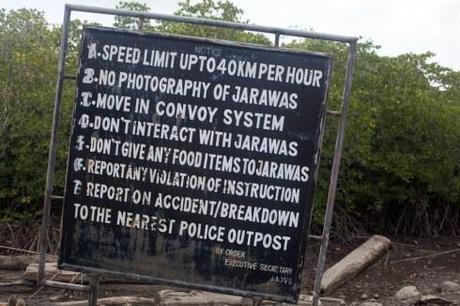

Long decried as a deeply immoral practice by groups such as Survival International, Search and by Intercontinental Cry, these safaris involve tourists being offered trips along the controversial highway, which runs through the middle of the Jarawa Indigenous reserve, to allow them to ‘spot’ members of the Jarawa. This 400-strong tribe of hunter-gatherers has only had friendly contact with outsiders since 1998, which makes them particularly susceptible to devastating epidemics of foreign diseases.

Numerous reports have demonstrated that ‘sighting’ these people is only the start of the sub-human treatment to which they are subjected. As exotic camera fodder, members of the Jarawa are frequently and degradingly pressured to dance for tourists in return for biscuits and fruit. This state of affairs has led India’s Minister for Tribal Affairs to call these tours both an “embarrassment” and a “disgrace”.

Despite the protestations of officials, events last year revealed that elements of the island’s law enforcement have had a role to play in facilitating or at least turning a blind eye to human safaris.

A police constable suspected of forcing Jarawa women to dance for tourists on film was arrested last January. The man, who was made visible in the footage in question, was identified by Jarawa women. In the video, he can be seen ordering these women to “Do it. Dance,” and directing them so that they could be more easily filmed.

This arrest constituted an uncharacteristically decisive action by island authorities who have previously failed to protect the Jarawa from damaging disturbances.

The island’s government has long claimed that the trunk road must remain open as it is a commercial ‘lifeline’ between the north and south, despite the fact that an alternative and quicker sea route is both possible and a potentially cheaper option for transport and tourism.

These same authorities have ignored several Indian Supreme Court orders to close the road, or inhibit its use for tourism, going back to 2002. As recently as January 2013, the Supreme Court passed an interim order banning all use of the trunk road for tourism purposes in a move that was praised by those concerned about the Jarawa.

In the interim order’s immediate aftermath, traffic along the trunk road decreased by two thirds. And despite the Andaman and Nicobar authorities tinkering with the Jarawa reserve’s buffer zone to allow two major tourist attraction to remain open, the benefits of the ban for the Jarawa were clear for all to see.

In an unfathomable move, the Supreme Court recently reversed its interim ban after just two months, allowing the road to be fully re-opened. Tour operators who had been unable to use the road were reportedly readying their vehicles within days of the decision, gearing up to resume the profitable ‘human safaris’.

This total u-turn was accompanied by equally distressing news that the Court had asked Andaman and Nicobar authorities whether they wanted to keep the Jarawa isolated or make an attempt at assimilation.

Any decision to ‘mainstream’ the Jarawa would, at present, violate the government’s official Jarawa policy, which states that:

“No attempts to bring them (the Jarawa) to the mainstream against their conscious will…will be made.”

Despite this, a number of politicians have and continue to call for an assimilation program against the Jarawa’s wishes.

That the Supreme Court would both lift the ban and propose that the Andaman and Nicobar government should have the final say over the Jarawa’s fate is shocking. Assimilation of Indigenous peoples has proven throughout history to have a devastating impact on the cultures, health and livelihoods of Indigenous populations. In some cases, it has even directly led to the extinction of entire peoples.

These recent court-government discussions indicate that whilst the trunk road remains open to business, and the 200,000 tourists who visit the islands annually, the Jarawa’s rights, and specifically their right to self-determination, will remain at risk.

Recognizing this threat and a need to pressure the Indian Supreme Court into reconsidering its decision so that island authorities can no longer ignore the issue, Survival International has launched a tourism boycott designed to cut off the ‘supply’ of tourists that are feeding the demand for exploitative human safaris.

Survival is also demanding, as they have been for some years, that the road be permanently closed and an alternative sea route put in place for travel. According to Survival director Stephen Corry, this would be “better for locals, tourists and the Jarawa a-like.”

Two hundred travel companies and thousands of tourists have been asked to join in the boycott. Thus far, thousands of prospective visitors have signed up and slowly but surely tour operators like Travelpickr and Orixa Viatges are joining them.

With the UN Committee for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination also expressing its considerable concern, pressure is mounting on the Andaman and Nicobar and also the Indian government once again to accord the Jarawa their rights and end human safaris once and for all.

To add your voice to the movement to end human safaris please sign the tourism boycott here.

Publisher’s Note: in a previous version of this article it was asserted that a police constable had just been arrested for being suspected of forcing Jarawa women to dance. IBN Live originally broke the story; however, according to the date stamp we observed on the IBN Live website, we were led to believe that the story had been released this week, when in fact it was released in February 2012. The present version of the article accounts for this fact. Our sincerest apologies for any inconvenience this may have caused.