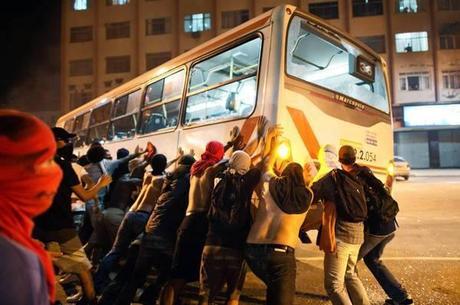

Demonstrators in Niteroi, near Rio de Janeiro, overturn a bus during protests. Clashes with police continued even as bus fare hikes were rolled back in two cities after protests on June 20, 2013.

When a tear-gas canister rattled around at Andrea Coelho’s feet, a masked young man picked it up and tossed it back at police. Right there, the kindergarten teacher decided she backed him and his fellow Black Bloc anarchists.

Coelho was one of thousands of teachers marching through central Rio de Janeiro to demand better wages and school conditions when police decided to disperse the demonstration. A few nights before, striking teachers occupying the city council building were beaten and dragged out by officers.

“It was the Black Bloc that protected me in that protest,” Coelho, 47, said at the beginning of a march last week that again descended into fighting between anarchists and police. “The police came in firing tear gas, hitting us with clubs. A young Black Bloc stepped right in between me and the police. If it weren’t for them, the police would have destroyed us.”

That sentiment has helped turn the anarchists in Brazil into a driving force behind protests in recent weeks. The demonstrations have lessened in size but not frequency since masses took to the streets in June, fed up with a litany of problems that mostly center on corruption, woeful public services, and big spending on the upcoming World Cup and 2016 Olympics.

More protests erupted Monday as demonstrators railed against the government auction of a big offshore oilfield, which petroleum unions think should remain completely in Brazilian hands, and the anarchists rallied in Rio’s historic center to support the strike of the teachers and oil workers.

Chased by demonstrators, police officers retreat during a protest near the state legislative assembly in Rio de Janeiro, on June 17, 2013.

Black Bloc is a violent [sic] form of protest and vandalism that emerged in the 1980s in West Germany and helped shut down the 1999 World Trade Organization conference in Seattle.

It’s clear that the masked, young Brazilians are following the main anticapitalist tenets of earlier versions, smashing scores of banks and multinational businesses during demonstrations and directly confronting riot police. The twist in Brazil, experts say, is that the tactics haven’t been quickly rejected by more mainstream protesters as they have been in places like Mexico, Chile and Venezuela. That could allow the movement to grow significantly.

During a protest in Rio last week, one young anarchist sprinted through a haze of tear gas as his throat burned and ears rang from a series of stun grenades police unleashed moments before.

Taking cover behind a battered metal newsstand in Rio’s historic Cinelandia district, the 25-year-old dreadlocked man steadied himself, tightened the straps of goggles he was

wearing, and yelled to a cluster of 30 black-clad demonstrators facing a line of riot police half a block away.

“Fight! Fight! Fight!” he screamed amid one of Brazil’s most violent protests since June. “It’s all going down right now!” The protesters hurled rocks at police. The officers responded with more stun grenades and tear gas, scattering the adherents of Black Bloc.

“People are fed up, and because of the police violence against peaceful protests, the Black Bloc returning that violence has become a way for people to express their indignation,” the young man said at the end of the protest. Like seven other Black Bloc adherents interviewed, he wouldn’t give his name, citing fears of arrest and the tactic’s hallmark anonymity. “I don’t expect a majority of people to support it, but I know they understand the anger.”

Black Bloc jumped via social media from the developed world to places such as Egypt and Brazil, where experts say it’s potentially more explosive because it feeds off deeper social unrest. It’s almost certain to affect Brazil’s World Cup and Olympics.

“The police, violence, poverty, hardship of life and economic inequality in Brazil can radicalize the situation to a greater degree,” said Saul Newman, a professor at Goldsmiths College in London whose research has focused on anarchism. “It’s hard to predict, but because of these conditions and because it’s new in Brazil, it could grow.”

In the interviews with Black Bloc adherents, all repeated what’s been heard in the U.S. and Europe before: They have no leaders, they operate in anonymity; there are no lists of demands for the government to meet.

Black bloc in Cairo, Egypt, January 2013.

Wearing black and covering their faces to make it hard for police to identify them, they head to demonstrations armed with slingshots, Molotov cocktails and homemade wooden shields with “BB” printed in white. Many look to be in their mid-to-late teens. Their aim is to use action like destroying the property of multinational companies and confronting riot police to disrupt a political system they say doesn’t allow for their participation and only represents entrenched economic interests.

But as in Egypt and elsewhere, the Black Bloc in Brazil says it also exists to protect other protesters from heavyhanded police tactics.

Brazilians widely consider their police poorly trained and violent, a force that is infamous for extrajudicial killings. A 2008 United Nations report said Brazilian police were responsible for a significant portion of the country’s 48,000 homicides the year before.

http://www.vancouversun.com/news/Support+anarchists+rising/9070769/story.html