The standing dead.

I live in the Laramie Valley in the Rocky Mountains, at 7000 feet elevation, far from any ameliorating marine effects. Winters are cold and long. What’s a lover of wild plants to do? Well … turns out plants are common right now, even herbaceous perennials and annuals! They're dead, of course. But if we look close, there's plenty of interest.

Musk or nodding thistle, Carduus nutans.

Plenty of plants to choose from.

I harvested a variety of dead plants, and brought them inside for macro portraits. As always, I saw things I hadn’t seen before. This time I was better able to capture them, as I now have a tripod. In the early days, no photographer would shoot without a sturdy base, even though it sometimes meant hauling a heavy tripod a long way to a precarious perch. Early cameras took so long to collect enough light for detailed images that a photographer couldn’t possibly hold one by hand.

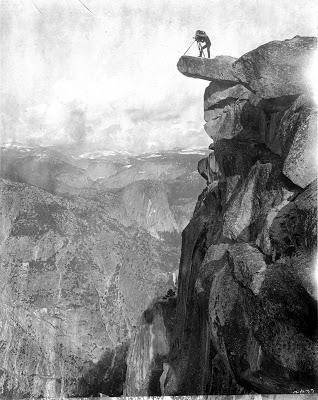

In the early days, no photographer would shoot without a sturdy base, even though it sometimes meant hauling a heavy tripod a long way to a precarious perch. Early cameras took so long to collect enough light for detailed images that a photographer couldn’t possibly hold one by hand.

WH Jackson makes a view from Glacier Point, Yosemite National Park (ca. 1884); source.

In his early work in the American West, William Henry Jackson typically used exposure times of 5 seconds or more for "views"—landscape photos. Though "fast" shutter speeds of 0.5 seconds were possible for action shots, detail and beauty were paramount in making views, and long exposures were necessary.Now our fast and clever cameras let us shoot hand-held in most situations, even for exposure times measured in seconds. In fact, some photographers are of the opinion that tripods will soon be obsolete.

“Between the much-improved high-ISO performance of modern imaging sensors and the excellent image stabilization technology available for most systems today, it would appear that we’re running out of reasons to use tripods anymore. After all, if we can shoot hand-held at shutter speeds as slow as 1.5 seconds and ISOs as high as 6,400 and still get great images, what do we need a tripod for?” Alvano SerranoBut there are situations where we need the stillness of a tripod—for example, in low light where a flash can’t be used, or for artistic long-exposure shots.

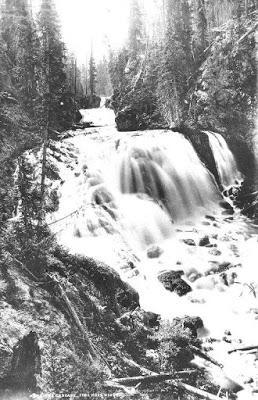

With exposure times of 5 seconds, William Henry Jackson’s waterfalls and streams were artistically blurred. Little Firehole Falls, Yellowstone National Park, 1874(?); source.

Two sessions of experimentation convinced me that shooting with a tripod is a hassle! (compounded by the challenges of macrophotography). I also decided it was worth it. With the camera on a firm foundation, I could carefully adjust settings and view results. A side benefit—I learned several camera features too.

Being so close to the subject, a macro lens produces a narrow depth of field, i.e. only a small part of the scene is in focus. This is not necessarily bad. Macros can create interesting compositions, for example a sharply-focused subject against a blurred background. But the depth of field can be too narrow to capture everything desired. In fact, insufficient depth of field is one of the two problems I’ve had with macrophotography (the other is poor focus—a tripod helps here too).

Many cameras have a mode dedicated to depth of field. In aperture priority mode (Av on my Canon Rebel), the aperture or opening for light can be adjusted to create less or more depth of field. This will be a smaller or larger f-stop number, which I know better than to try to explain. See A Tedious Explanation of the f/stop (only a little tedious).

Then I found I needed more light. But in aperture priority mode, how can I adjust anything else? The camera manual explained that I could still use exposure compensation, even in Av mode. Sure enough, it worked.

With the stillness of the tripod, I could look at settings in the LCD monitor, adjust them, use longer exposure times without worrying about camera shake, adjust depth of field to my taste, bring into sharp focus things I wanted to feature, and then press the button.

Abstract #1—showy milkweed (Asclepias speciosa)

All this may seem complicated, with lots of details to remember—not something I enjoy. And this is just the simple stuff; there are many more options! But I like the results. After some early frustration, it became interesting and even fun. And that’s what we look for mid-winter in Laramie.

Milkweed pods—dry, open, empty. Most of their seeds have been cast to the wind.

Pod is about 9 cm long.

Abstract #2—Scotch thistle (Onopordum acanthium)

The pits once held seeds (technically achenes or cypselas).

Nodding head of nodding thistle (also first two photos in post).

A forest of phyllaries (bracts).

Dock, Rumex sp.

Dock’s winged fruit are about 4 mm across. The brown bulges are called callosities or tubercles, and are useful for identification.

What’s this lovely arrangement?

It's yellow sweetclover, Melilotus officinalis. Dried pods (legumes) are about 3 mm long; each contains a seed.

I wonder—how easy will all this be outside? My tripod can hold the camera as low as 4.5 inches above the ground. Will I be able to capture blooming flowers? (Yes … I’m dreaming of warmth, verdant growth, and bright colors!)

Pasque flower.