"An Oak, whose leaves are as large, and which bears such large fruits, is well suited to attract the attention of lovers of foreign cultures, and to find a place in the parks and gardens of a large extent." FA Michaux, 1810 (translated from French). TreeLib photo.

In 1785, 15-year-old François-André Michaux traveled to America with his father, André Michaux, Royal Botanist to Louis XVI. They had been provided a commission and instructions to collect unusual plants and useful trees. The latter were especially valuable, as European countries were running out of wood. Like fossil fuels today, wood was critical for transport (e.g., large armadas of wooden ships!) and in manufacturing (charcoal for iron smelters, glassworks, and more).Michaux the younger returned to France in 1790, as did his father six years later. Together they went to work on what would become the great Histoire des Arbres Forestiers de l’Amerique Septentrionale. It was published in 1810 in French by François-André alone, as his father had died in 1802 (subsequent references to "Michaux" in this post are to the younger). It would be published in English as The North American Sylva (1).

Quercus macrocarpa, Over Cup White Oak (today's Bur Oak). Michaux 1810; BHL.

Among their discoveries was an oak with exceptionally large acorns, the basis for the species name given by Michaux—macrocarpa. The common name at that time, Over Cup White Oak, refers to the sizable cup that sometimes nearly covers the nut. Unfortunately the wood was "inferior in quality to that of true white oak" (2).Quercus macrocarpa is one of nearly 100 oak species in North America north of Mexico (3). While it's easy to recognize a tree as an oak (with leaves), trying to distinguish among oak species can be very frustrating. Many oaks hybridize, acorns often are lacking or immature, and the tiny flowers are similar among species and not useful in identification. Botanists generally rely on leaves and twigs. But leaves are variable, even on a single tree, so one must collect a representative selection of mature sun leaves (not shade) for identification. Twigs with mature buds can be helpful (FNA).

Male catkins (flower clusters) of Bur Oak, tiny male flowers in insert. Oak flowers are unisexual, and trees are monoecious (with flowers of both sexes). MWI photo.

In South Dakota however, we have it easy. Bur Oak is the only oak species native to the state. This lack of diversity is disappointing but it does make life simpler. And we will take a close look at our oak anyway. Nothing wrong with enjoying a tree.Michaux considered the Bur Oak "a very beautiful tree ... its foliage appeared to me to be very thick and quite dark green. Its leaves, larger than those of other species which grow in the United States, often are 40 centimeters in length, and 20 centimeters at their widest part. They are crenellated at their summit ... and cut very deeply in their lower two thirds."

A classic Bur Oak leaf: crenulate at the tip, deeply lobed below, fiddle-shaped overall.

Gazing up through Bur Oak canopies is a lovely way to spend an afternoon.

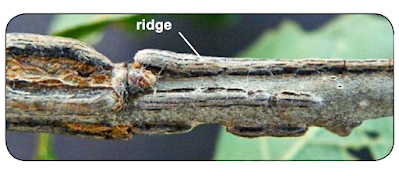

All oaks have clusters of terminal and lateral buds at the tips of twigs, which helps in recognizing leafless oaks in winter. Older twigs of Bur Oak often have corky ridges.

Terminal and lateral buds clustered at tip of a Bur Oak twig. MWI photo.

Corky ridge on an older Bur Oak twig. Nature Manitoba.

An acorn is by definition the fruit of an oak; illustration from Cronodon.

The fruit of the Bur Oak is, of course, an acorn—a nut in a cup. Those of the Bur Oak are usually distinctive: "The acorns, oval in shape, are also [like the leaves] larger than those of all other species of Oak trees found in North America ... These acorns are contained, up to two thirds of their length, in a thick, unequal cup, and whose edges are lined with loose and flexible filaments" (Michaux 1810).The overlapping scales of the cup of the Bur Oak are bumpy (tuberculate). Those near the rim have elongate tips, which make the cup look fringed—the basis for another common name, Mossy-cup Oak. But the fringe may be absent, as Michaux noted. "Sometimes, however, when these Oaks are found in the middle of dense forests, or the summers are not very hot, these filaments [elongate tips] do not appear, so that the edge of the cup is completely plain, and appears as if folded internally."

Sometimes the cup nearly encloses the nut. Bur Oak acorns in Missouri. Grey Wanderer photo.

When I arrived at Newton Hills State Park in far eastern South Dakota last month, I secured a site in a small area for tent campers in an oak opening (Bur Oaks prefer open habitat). Having forgotten my trip to eastern Nebraska long ago, I was surprised by the stature of the Bur Oaks. Being a westerner, it's not what I'm used to.

Canopies composed of beautifully sinuous branches.

Another campground, more oaks.

Everything about them was photogenic, including the bark.

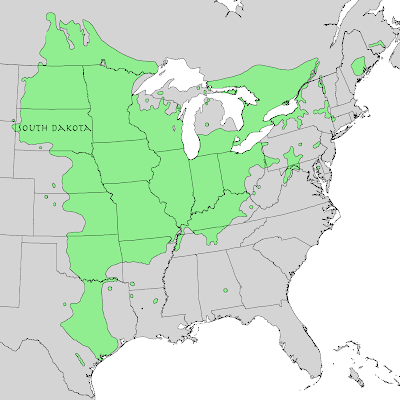

Quercus macrocarpa; from USGS digitized "Atlas of United States Trees" by Elbert L. Little, Jr. Source. This is a 1971 map; Bur Oak is now known to grow farther west in northeast Wyoming.

Bur Oak has a large range, from New England through the Midwest and south nearly to the coast in Texas. Its western limit is near the Hundredth Meridian as far north as Nebraska. But it grows farther west and north in the Dakotas, Wyoming, Montana and Manitoba. In fact it's the most northerly of our native oaks, being the most cold tolerant (Nelson et al 2014). Less hospitable habitat may be reflected in stature (4). These are the Bur Oaks I know—scrappy little trees or even shrubs.

Bur Oaks in front of Ponderosa Pines, northeast Wyoming. Matt Lavin photo.

Western Bur Oak acorns are smaller than those of eastern trees; note thumb for scale. Matt Lavin photo.

Notes

(1) The American Sylva has a complicated history, with at least a dozen known editions in multiple printings and formats (Constantino 2018). Most recently (2017), the New York Botanic Garden published 277 color plates from the Sylva in The Trees of North America: Michaux and Redouté’s American Masterpiece.

(2) Not everyone agrees with Michaux. According to the Flora of North America, "Wood of Q. macrocarpa is similar to that of Q. alba [White Oak] and produces one of the best and most durable oak lumbers."

(3) North American oaks are divided into three sections: white, red, and golden. Bur Oak belongs to the white oaks, characterized by leaves with no bristles on the tips or lobes, acorns produced every year (if conditions allow), and acorn cups with tuberculate (bumpy) scales (Nelson et al. 2014).

(4) Smaller Bur Oaks in the west and northwest are sometimes recognized as Quercus macrocarpa var. depressa (see Tropicos for the name's origins). In a study of Q. macrocarpa in the Black Hills and parts of New Mexico, Maze (1968) saw evidence of past hybridization with the more southern Q. gambelii; ongoing hybridization is unlikely because today's species are not sympatric. Maze recognized hybrids based on leaf and cup morphology, not tree stature. However one hybrid was described as being shrubby. In Flora of North America, the smaller form is considered an endpoint in clinal (continuous) variation from east to west, but more study may support recognition of var. depressa.

Sources (in addition to links in post)

Costantino, Grace. 2018. Exploring the First American Silva. Biodiversity Heritage Library Blog.

Maze, J. 1968. Past hybridization between Quercus macrocarpa and Q. gambelii. Brittonia 20:321–323.

Michaux, François-André. 1810. Histoire des arbres forestiers de l'Amérique septentrionale. Paris, L. Haussmann. (Quercus macrocarpa p 34–35 and Plate 3). BHL

Nelson, G, et al. 2014. Trees of eastern North America. Princeton U Press.

This is my June contribution to the monthly gathering of tree followers kindly hosted by The Squirrelbasket. More news here.