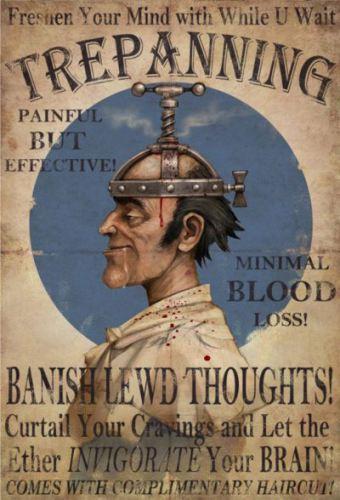

In the dark ages of medicine, meaning anything before 50 to 100 years ago, those afflicted with epilepsy were treated, how shall we say, less than compassionately. They were often thought to be infected by some evil miasma, or possessed by a lurking devil or witch or warlock, or were afflicted with some contagious process. They were isolated from society, feared and shunned by all, and often subjected to horrific treatments – everything from freezing water to cutting holes in the skull to let out the evil spirits (trepanning).

This is not an uncommon reaction when people are faced with things that they don’t understand. And 100 years ago the medical profession actually understood very little.

A case in point would be Philadelphia physician Dr. Ralph Spangler who suggested that rattlesnake venom, which interestingly he had been using to treat tuberculosis (go figure), might be useful in treating epilepsy. He published an article about a Texas man who had been bitten by a rattlesnake and subsequently the epileptic seizures that had plagued him suddenly ceased. In this empirical observation of a single case he jumped to the profound conclusion that snake venom cures seizures. Thankfully cooler heads prevailed and other physicians pointed out that snake venom not only didn’t, and couldn’t, help epilepsy but rather frequently caused allergic reactions as well as hemolytic destruction of the blood. Not pretty.

The history of medicine is replete with such examples.