War Song

Written by Jessica Wright Buha

Directed by Jack Dugan Carpenter

Berger Pk. Cultural Center, 6205 N. Sheridan (map)

thru April 19 | tickets: $25 | more info

Check for half-price tickets

Read review

Good intentions don’t make this song harmonious

The Plagiarists presents

War Song

Review by Clint May

“It must be admitted, truth compels me to admit, even here in the presence of the monument we have erected to his memory, Abraham Lincoln was not, in the fullest sense of the word, either our man or our model. In his interests, in his associations, in his habits of thought, and in his prejudices, he was a white man.”

–Frederick Douglass, “Oration in Memory of Abraham Lincoln” delivered at the Unveiling of the Freedmen’s Monument, 1876

Few other speeches from the post Civil War era sum up the conflicted attitudes of African Americans towards Abraham Lincoln, recently and instantly enshrined in the American mythology. Douglass makes many pointed references throughout, perhaps galled by the patronizing quality of the monument in front of which he was speaking. His absence from The Plagiarists War Song is conspicuous considering its content. Utilizing the development of the lesser-known speech “The Negro as Soldier” by Christian Fleetwood to explore race relations in America, the production is frustratingly one-dimensional. Rather than bringing this hero of the Civil War to life, he and his supporting characters feel more like caricatures. Only the songs themselves lend any genuine depth of emotion.

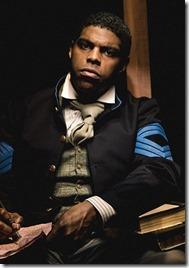

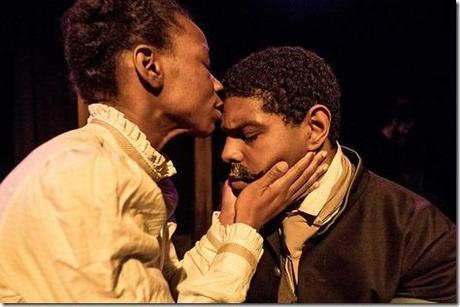

Quickly rising to the rank of Sergeant Major in the Colored Infantry, Christian (Breon Arzell) was awarded the Medal of Honor for saving the flag during battle. We encounter him years later at home with wife Sara (Jyreika Guest), fretting over the finer details of his speech. To aid him, he resurrects the “ghosts” of Abraham Lincoln (Derik Marcussen) and Walt Whitman (Christopher Marcum). Able to be plainly seen, talk and even cook a pie, the ghosts interact with both Christian and Sara as if they were regular houseguests. Sara is staunchly in favor of leaving America and returning to Africa, having never felt that the United States was her true home given all the abhorrent acts of discrimination still taking place. Christian feels that to do so would be to admit defeat too soon after so much blood had been shed to move the races towards harmony. He sees the glory of the soldier in war as a defining factor in advocating for universal brotherhood. Caught in the middle, “Mr. L” begins as his idealized self but reveals parts of his less admirable character when prompted by Sara’s ire—notably, his idea that the two races would be better off being separated again seeing as how their forcible removal from their homeland almost dissolved the Union.

Lincoln’s mutability of mind is well known. As W.E.B. Du Bois (whose work informs parts of War Song) would later say to sum up our continued frustration at painting a continuous portrait, Lincoln was “big enough to be inconsistent.” A person can—and many have and always will—cherry pick quotes and speeches to create any Lincolnian viewpoint they would like. Any time he’s brought up in works of art, it’s bound to create a degree of consternation because the man himself is such an enigma. Separating his morality from his political maneuvering can drive a historian to drink. It would be safe to say that it would be his relationship with Frederick Douglass and the achievements of African American’s fighting in the Civil War that had a profound impact on his personal racial views outside his moral distaste for slavery. As Christian and Sara struggle to make sense of their identity, Lincoln’s failings and virtues are trotted out and thrown against the other as they battle.

Many of Jessica Wright Buha’s choices elude explanation beyond the conspicuous absence of Douglass (himself a vocal advocate of enlistment for African Americans). Reduced to an unpleasantly scowling singularity of mind, Sara is not allowed her own ability to bring forth historical characters. Whitman is a clumsily effete dandy, mostly fussing over a pie while making the occasional soliloquy from his repertoire of Civil War poetry in which, among other things, he finds beauty in death. Then there’s a final moment in which, suddenly fed up with the inadequacy of words, Christian aims a musket at Lincoln. However metaphorical such an action might be (Abe’s already deceased and the musket is not loaded), it reeks of dramatic desperation and is totally out of established character.

Given this, director Jack Dugan Carpenter and cast struggle in vain to find anything in their respective historical counterparts that makes them come to life. Too often they feel tuned towards a particularly lively Discovery Channel reenactment. Only near the end do the tensions and stakes rise. They just feel too often to know that they are history and their dialog is too closely hewed to politically correct recitation to break free into characterization. It might have been better to remove all the dialog and make this true to its name—only songs and poems about war. Backed up by the trio of Wyatt Kent, Sean McGill and Kathryn Miller, the absolutely appropriate venue of the Berger Park Coach House begins to fade away on the melancholy melodies interspersed throughout.

Fleetwood is a underappreciated figure of the Civil War and civil rights. To sing his unsung praises and by extension the achievement of African American soldiers is an always admirable goal. As his speech points out, their achievements were unjustly and quickly forgotten after the treaties are signed. What’s more, he inspires us to move beyond petty distinctions of black and white to simply people. Perhaps that is meant to make us ignore his initially imploring approval from two deceased white gentlemen instead of Sojourner Truth. [Sidenote: I’d love to see a play where another group fight for equal rights by pointing out the nobility of things that don’t involve war]. It’s a sadly still contemporary (and very old) set of arguments you might have heard recycled in the fight for LGBT rights vis-à-vis that toughness and devotion to country in military efforts should result in equality. War Song makes inexplicable choices, but it can’t be faulted for not making a good point.

Rating: ★★

War Song continues through April 19th at Berger Park Cultural Center, 6205 N. Sheridan (map), with performances Thursdays at 7:30pm, Fridays and Saturdays at 8pm. Tickets are $15-$25, and are available online through BrownPaperTickets.com (check for half-price tickets at Goldstar.com). More information at ThePlagiarists.org. (Running time: 90 minutes, no intermission)

Photos by Joe Mazza

artists

cast

Breon Arzell (Christian Fleetwood), Jyreika Guest (Sara Fleetwood), Derik Marcussen (Abraham Lincoln), Christopher Marcum (Walt Whitman), Wyatt Kent (Musician, trumpet), Sean McGill (Musician, drums), Kathryn Miller (Musician, guitar, violin)

behind the scenes

Jack Dugan Carpenter (director), Emma Cullimore (costume design), Gregory Peters (production manager), Katie Ritchie (stage manager), Melissa Schlesinger (props and set design), Samantha Decker (assistant director), John Jacobson (lighting design), Kathryn Miller (music director), Mallory Nees (original music composition, music arranger), Ned Ricks (Civil War expert), Joe Mazza (photos)

14-0333