The Laramie Project:

10 Years Later

By Moises Kaufman, Leigh Fondakowski,

Greg Pierotti, Andy Paris and Stephen Belber

Directed by Greg Kolack

Redtwist Theatre, 1044 W. Bryn Mawr (map)

thru April 7 | tickets: $25-$30 | more info

Check for half-price tickets

Read entire review

An update on Hate – and Hope

Redtwist Theatre presents

The Laramie Project: 10 Years Later

Review by Lawrence Bommer

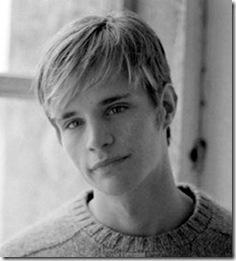

October 12, 1998—that’s the night of horror when 23-year-old Matthew Shepard was tied to a fence. As he faced the lights of college town Laramie, Wyoming, he was tortured to death by creatures named Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson. (McKinney, the more evil perpetrator, inflicted 21 vicious hits on Matthew, with a brand new gun that supposedly made him a man.) The equally young predators singled out this frail young gay man because he seemed the perfect target, friendly and trusting enough to trust them to give him a ride. But also because he was gay. After robbing him of chump change, the bullies went on to inflict unspeakable torment on this sweet soul—not just that terrible “fence-icruxion” but six days of agony in a hospital before death freed him of more agony.

Richly orchestrated by Greg Kolack, the eight performers in this Redtwist Theatre’s Chicago premiere deliver a combustible collage of well-balanced, tell-all anecdotes and observations from Laramie citizens, police, and scholars. We also hear interviews with Matthew’s outspoken mother Judy and both killers. This crazy-quilt confessional gives hope and takes it away. It confirms, confuses and contradicts stereotypes about Westerners, Republicans, and cowboy justice. Though never preaching to the choir, it finally affirms that, though Matthew died for no one’s sins, his unwanted sacrifice may someday equal in good deeds the sheer evil that caused it.

Returning to the scene of the crime (in a state that served as the setting for “Brokeback Mountain”), the Tectonic actors discovered that the town, the home of the University of Wyoming, has grown through dirty coal-mining and other environmental exploitation, only recently succumbing to the recession. Still haunting the locals is the stigma of a very speakable 1998 hate crime, an assassination which will be as associated with this town as Chernobyl, Littleton and Johnstown are with their calamities. The university now has a Rainbow Resource center and a barely visible Matthew Shepard Memorial Bench. The town also sponsors an annual AIDS Walk; afterwards drag queens entertain the patrons at a cowboy bar.

Yet, just as Tyler Clementi’s suicide proves that bullying is far from over, Shepard’s name both sums up and predicts homophobia, just as the Stonewall riots do resistance. (Happily, it’s also on the name of the nation’s first anti-hate crime legislation.)

Understandably but pathetically, many Laramie citizens want to find a phony “closure” on the gratuitous outrage. Egged on by a shamefully unbalanced and utterly fallacious “20/20” update in 2004, they try to believe that it wasn’t a hate crime after all—it was a drug deal gone wrong, a robbery that got out of hand by meth-addled muggers. Blaming the victim, they dismiss the supposedly unwary Matthew as in the wrong place at the wrong time. But for McKinney and Henderson he was the right victim as well.

As the cops who knew the facts point out, this mythologizing is weird wishful thinking. McKinney and Henderson pretended to be gay to lure Matthew into their car (much as homosexual lovers/thrill-killers Leopold and Loeb lured Bobby Franks into their car over 70 years before).

As the 2008 anniversary forced Laramie to face its ugliest hours, the Laramie Boomerang blamed outsiders with their special agenda for stirring up bad memories and preventing the town from putting its pain behind them. “Let the boy go,” they plead. But, as an opponent says, “They want to write the murder off” as the work of two bad apples, not the homophobia that fed their rage. As a folklore specialist at the university explains, a town beset with scandal and shame will refuse to “own” their homegrown horror, abandoning responsibility by ignoring the facts and manufacturing a self-serving “urban myth.”

Only three people know for sure what happened that autumn evening. One is dead. When interviewed, Henderson, however, seems almost remorseful, ashamed that he was such a follower that he couldn’t stand up to the demonic McKinney. But in McKinney’s interview that thug all but admits it was a hate crime. This Nazi sympathizer– who, improbably, has always been kept imprisoned with Henderson no matter what prison they’re moved to (sounds like male bonding of the worst variety…)—says he hates gay people. (The interviewer, alas, never asks him if he has ever known any or if he ever felt any of Matthew’s pain.) Though his mother was brutally raped and murdered in Laramie, that ugliness apparently hardened McKinney to Matthew’s suffering. He found the young man “overly friendly,” the perfect mark for a robbery turned homicide. He’s more upset that the prison T.V. only gets ten channels.

As if to balance the indictments, the play digresses in the second act to depict the Wyoming legislature’s enlightening debate about a “defense of marriage” act that came to a surprising ending. An interview with the indomitable Judy Shepard further confirms our belief in American integrity and ultimate justice. (Judy Shepard will appear this Saturday in a benefit at Redtwist Theatre.)

Ironically, the infamous fence, from which a grievously injured Matthew stared down at a town without pity, has been torn down. (It should have been as preserved as fragments from the original Cross or panels from the AIDS Quilt.)

Happily, Tectonic’s “Laramie Projects” provide a powerful cautionary tale, a learning curve that rises to the occasion. Despite the town’s denial, a “new normal” has changed Laramie forever—and the nation. Matthew, who never sought martyrdom or sainthood, got no justice that night but at least his murderers’ lives are stunted forever. Tectonic and Redtwist’s triumph is to try to dig some good out of unfathomable evil. Theater, as always, appeals to our better angels. Redtwist deserves kudos for speaking so much truth to hate.

Rating: ★★★★

The Laramie Project: 10 Years Later continues through April 7th at Redtwist Theatre, 1044 W. Bryn Mawr (map), with performances Thursdays-Saturdays at 7:30pm, Sundays at 3pm. Tickets are $25-$30, and are available by phone (773-728-7529) or online here (check for half-price tickets at Goldstar.com). More info at Redtwist.org. (Running time: 1 hour 50 minutes, which includes one intermission)