The Invisible Man

Adapted by Oren Jacoby

Based on novel by Ralph Ellison

Directed by Christopher McElroen

at Court Theatre, 5535 S. Ellis (map)

thru Feb 19 | tickets: $35-$65 | more info

Check for half-price tickets

Read entire review

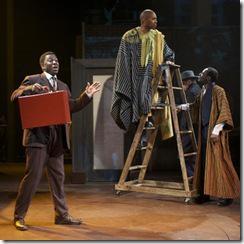

‘Invisible Man’ a major achievement and largely thrilling ride

Court Theatre presents

The Invisible Man

Review by Catey Sullivan

Ralph Ellison’s sprawling novel “Invisible Man” all but defies adaptation. It’s not just the epic length of the seminal book, although its 600+ pages provide a daunting challenge to would-be adaptors trying to wrestle it into a manageable few hours traffic on stage. The piece is as deep as it is long: As it traces the journey of a black man through 1930s America, every last paragraph in “Invisible Man” is thick with subtext and symbolism. The story is at once an epic, a parable, an allegory, a coming-of-age saga and a Picaresque adventure. Beyond the sheer difficulty of transforming the source material, those who would stage “Invisible Man” have for decades faced another formidable obstacle. Ellison, and his estate after his death, simply refused to grant the rights to any and all who would attempt to make a film or a stage play from the book.

There’s not a single passage in Jacoby’s adaptation that isn’t taken directly from the book, something which is both an artistic triumph and an audience handicap. The former is due to the relentless, emotional drive of Invisible Man; the story hits both the head and the heart with compelling force. The handicap is apt to impact anyone who sees the production without being familiar with the book. “Invisible Man”, like Homer’s “Odyssey” and James Joyce’s “Ulysses”, has kept scholars and students busy since its publication.

There’s so much going on both overtly and between the lines of Invisible that it almost requires a companion tome of critical analysis if one is going to fully appreciate it. Pared down to a series of events on stage, the story maintains high intensity emotions, but isn’t an easily accessible piece of theater. As the often surreal, impressionistic narrative jumps through time and place, audiences may well be left asking where the connective tissue between episodes is, and what they mean. In other words, Jacoby’s adaptation captures the action but not always its significance.

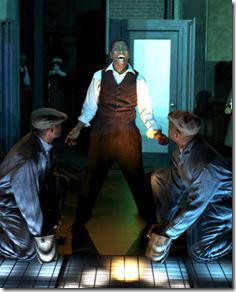

The most inaccessible portion of the production comes following an industrial accident, wherein the Invisible Man – working in a paint factor – is caught in an explosion and winds up coated in white paint. From the basement of the factory, the action abruptly skips to a nightmarish hospital where sadistic doctors and nurses administer a primitive, brutal form of electric shock treatment on the Invisible Man, talking of lobotomies while he screams and thrashes uncontrollably. It’s a virtually context-free scene that ends as abruptly as it begins, and seems to have little connection to anything else. A bit of additional background would go a long way here toward making the painful scene less jarringly out of place.

|

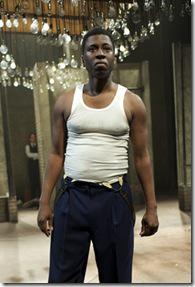

That said, Invisible Man is a major achievement and a largely thrilling ride from start to finish. As the tormented beleaguered and ultimately enlightened title character, Teagle F. Bougere does the heavy lifting here, and magnificently so. Both narrating the action and central to it, he’s on stage for all of the piece’s three-hour running time. His energy and range are formidable, beginning as an eager, naïve young man certain that the world will reward his intelligence, integrity and ambition and incrementally morphing into the disillusioned, unseen outcast. Even if it isn’t entirely clear what quasi-magical metaphorical forces send Invisible Man to live (no spoiler – Invisible Man starts at the end and winds back forward) living in a cave illuminated by more than 1,000 light bulbs beneath the New York City streets, the components of his journey there are vividly, memorably etched.

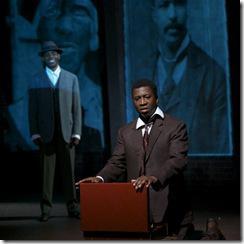

The ensemble cast weaves a tale of woe and triumph on a largely bare stage, often backed by Alex Koch’s haunting video projections, which are created from more than 300 archival films, 150 Library of Congress photos and projected on some 16 on-stage surfaces.

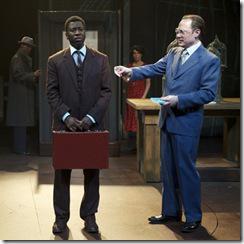

A.C. Smith is also memorable, first as an African American college president who turns out to be as backhanded and unjust as any of the obviously, egregiously racist white folks the Invisible Man encounters down south and later as a Black Nationalist intent on fomenting rebellion. Lance Baker stands out as an almost unwatchably slimy southern good ol’ boy (who is in fact, as bad as they come), and then veers 180 degrees to portray a tormented young man of means disgusted by the racism and injustice that surrounds him. As Norton, a philanthropist whose beneficence in funding an all-black college is actually more self-aggrandizement than altruism, Bill McGough calls to mind the dangerously ignorant, showy liberalism of the rich white daughter in Native Son. In proclaiming that blacks are his “destiny,” Norton reveals that he views the entire race as a prop to help him fulfill his own dreams rather than a vast population with limitless potential to fulfill their own.

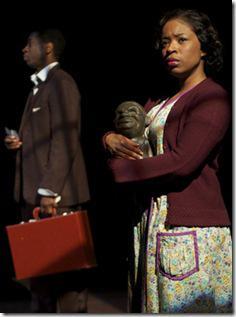

The primary flaw in Ellison’s opus is his lack of female characters, something that shows up on stage. In the book, women are either temptresses or earth mothers, and only superficially sketched in both instances. That’s evident in Court’s production, with the trio of supporting women (Kimm Beavers, Tracey N. Bonner, Julia Watt) relegated primarily to the background. Given the scope of the production, that’s almost a quibble. In its exploration of being black in the U.S. of A., “Invisible Man” was (and is) a monumental, ground-breaking piece of literature. The same can be said of its staging.

Rating: ★★★½

The Invisible Man continues through February 19th at Court Theatre, 5535 S. Ellis (map), with performances Wednesdays-Thursdays at 7:30pm, Fridays at 8pm, Saturdays at 3pm and 8pm, Sundays at 2:30pm and 7:30pm. Tickets are $35-$65, and are available by phone (773-753-4472) or online here (check for half-price tickets at Goldstar.com). More information at InvisibleInChicago.org. (Running time: 3 hours 10 minutes, which includes two intermission)

All photos by Michael Brosilow