Electrifying world-premiere from start to finish

Review by Catey Sullivan

Vaudeville by way of existential absurdism by way of a scathing commentary on a country where murder is committed without reprisal - so long as the victim has an abundance of melanin. They're all elements of Antoinette Nwandu's explosive Pass Over , a drama that reshapes Waiting for Godot and the Bible's Book of Exodus into a scorching condemnation of a world where skin color brands you as a target and open season never

Directed by Danya Taymor, Steppenwolf's 80-minute production is electrifying from start to finish. It is both riveting and excruciating, thanks to Nwandu's uncompromising ability to lay bare the realities of an urban wilderness defined by a seemingly unbreakable cycle of fear, brutality and dreams forever deferred.

The Bible's Moses spent 40 years wandering in the desert wilderness, leading his tribe in a quest to find the elusive Promised Land. In , Moses is a young black man who, like his Biblical namesake, is also seeking something better. But as the days and nights blur together, Moses (Jon Michael Hill) and his best friend Kitch (Julian Parker) seem no closer to escaping the exile imposed on them by systemic poverty, violence and brutal oppression.

For Moses and Kitch, the world is as barren and grim as any desert. Their yearning to break free is heartbreaking in its futility - there's no sign of deliverance from a higher power in , no burning bush, no heavenly promise of a promised land. And there's this: Biblical Moses spent 40 years in the desert. Moses and Kitch are part of an exile that goes back centuries. Half a millennia after the first slave ship set sail, they're still wandering.

Yet in this all-but unimaginably bleak landscape, Nwandu spins a banquet of gorgeously rhythmic and descriptive poetry. Moses and Kitch speak in a vernacular both hypnotic and harsh, a language where the ugliest slurs are reclaimed and transformed into something that evokes a bond of brotherhood. Nwandu also instills with humor. The juxtaposition of laughter, violence and poetry is jarring, brilliant and mesmerizing.

Like Waiting for Godot, focuses on two men trying to decide whether the wait - whether life itself - is worth the effort. Where Godot 's Didi and Gogo long for the arrival of the mysterious Godot, Moses and Kitch speak of yearning to "pass over." The phrase has multiple meanings in Nwandu's drama: At the heart of all of them is Moses and Kitch's hope that they've been chosen for something other than a stunted lifetime of soul-killing futility.

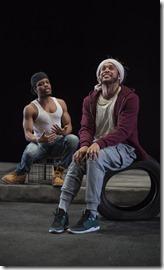

Instead of the gnarled tree of Samuel Beckett's classic, Moses and Kitch live under a battered streetlight. Like Didi and Gogo, they play games, try to rid their boots of irksome pebbles they can never quite shake out and are so closely linked they can finish each other's sentences.

Nwandu's dialogue carries distant echoes of iconic duos such as Laurel and Hardy or Abbott and Costello. But unlike the comics of yore, Moses and Kitch live in a world filled with a smothering sense of dread. Gun shots ring out at random, causing both to dive for cover mid-sentence.

In Nwandu's airtight plotting, the menace comes from outsiders. A preternaturally cheerful, dandified man with a picnic basket (Ryan Hallahan) shows up first. He smiles, offers Moses and Kitch food (including good old American apple pie), and speaks with the refined, honeyed drawl of an antebellum southern gentleman.

Later, a cop (also played by Hallahan) materializes, rising from upstage in a way that's deeply unsettling and not quite human. Without saying a word, he fills the stage with the sort of awful dread that accompanies dead-of-the-night sleep paralysis - that terrifying state where you cannot seem to move or breathe and cannot fully tell whether you're awake or asleep. The cop's appearance seems to suck all the air from the room, suffocating all within.

Taymor's three-man cast is extraordinary. As Moses, Hill travels the length of the emotional spectrum with crushing impact. Toward the end of the piece, Moses utters a plea that almost breaks the fourth wall - it's a moment that embodies the rage of a thousand generations and it is spectacular in its urgency.

Parker delivers a star-making turn, giving Kitch a physicality that's as powerful as the most exquisitely rendered ballet. He's in near constant motion, sparking with a restless tension that cannot be tamped.

Hallahan gives the polite stranger shadings of a shark circling for the kill. His smile is filled with knives, and when he finally reveals himself in the final scene, it's as horrific as it is indelible. As the cop, he barely says a thing, but the monstrousness of the character is as vivid and frightening as sudden bloodshed.

Wilson Chin's spare set captures the stark ugliness of a corner left to rot; long forgotten by those with the means to make it better. And with the light and sound design by (respectively) Marcus Doshi and Ray Nardelli, the corner becomes a world entire.

is the rare drama that will keep you utterly rapt from start to finish, while also spinning an unforgettable commentary on the problems that plague 21st century America. There's nothing preachy about it, even as it makes its points with stunning force. If you miss this production, you'll have missed one of the seminal dramas of the year - perhaps of many, many years.

continues through July 9th at Steppenwolf Theatre, 1650 N. Halsted (map), with performances Tuesdays-Fridays at 7:30pm, Saturdays 3pm & 7:30pm, Sundays 3pm. Tickets are $20-$89, and are available by phone (312-335-1650) or online through their website (check for half-price tickets at Goldstar.com ). More information at Steppenwolf.org. (Running time: 80 minutes, no intermission)

Photos by Michael Brosilow

Ryan Hallahan (Mister, Ossifer), Jon Michael Hill (Moses), Julian Parker (Kitch), Gregory Geffrard (u/s Moses), Jeffrey Owen Freelon Jr. (u/s Kitch), Christopher Sheard (u/s Mister, Ossifer).

behind the scenes

Danya Taymor (director), Wilson Chin (set design), Dede M. Ayite (costume design), Marcus Doshi (lighting design), Ray Nardelli (sound design, original music), Cassie Calderone (stage manager), Kathleen Barrett (asst. stage manager), JC Clementz (casting director), Aaron Carter (artistic producer), Tom Pearl (director of production), Tasia Jones (asst. director), Aram Kim, Zhao Mingshuo (asst. scenic designers), Kaili Story (asst. lighting design), Sarah Illiatovich-Goldman (script supervisor), Lucas Garcia, Lauren Katz (additional research), Aaron Stephenson (sound board operator), Jacob Brown, Kevin Lynch, Mark Vinson (additional carpentry), Bennett Seymour (additional properties), Sarah Diefenbach (wardrobe crew), Gianna Petrosino (stage manager apprentice), Rebecca Adelsheim, Rebekah Camm, Gregory Geffrard, Lavina Jadhwani , Neel McNeill, Derek Matson, Derek McPhatter, Leean Torske (audience engagement associates), Anne D. Shapiro (artistic director), David Schmitz (executive director), Michael Brosilow (photos)

Tags: 14-0617, Aaron Carter, Aaron Stephenson, Anne D. Shapiro, Antoinette Nwandu, Aram Kim, Bennett Seymour, Cassie Calderone, Catey Sullivan, Christopher Sheard, Danya Taymor, David Schmitz, Dede M. Ayite, Derek Matson, Derek McPhatter, Gianna Petrosino, Gregory Geffrard, Jacob Brown, JC Clementz, Jeffrey Owen Freelon Jr., Jon Michael Hill, Julian Parker, Kaili Story, Kathleen Barrett, Kevin Lynch, Lauren Katz, Lavina Jadhwani, Leean Torske, Lucas Garcia, Marcus Doshi, Mark Vinson, Michael Brosilow, Neel McNeill, Ray Nardelli, Rebecca Adelsheim, Rebekah Camm, Ryan Hallahan, Sarah Diefenbach, Sarah Illiatovich-Goldman, Steppenwolf Theatre, Tasia Jones, Tom Pearl, Wilson Chin, Zhao Mingshuo

Category: 2017 Reviews, Catey Sullivan, Drama, New Work, Samuel Beckett, Steppenwolf, World Premier