Gypsy

Jule Styne (music), Arthur Laurents (book)

and Stephen Sondheim (lyrics)

Directed by Gary Griffin

Chicago Shakespeare at Navy Pier (map)

thru March 23 | tickets: $48-$88 | more info

Check for half-price tickets

Read review

A stage classic in every way

Chicago Shakespeare Theater presents

Gypsy

Review by John Olson

It’s often said that Gypsy is the greatest American musical, and one that could stand on its own even without its songs. This production, directed by Gary Griffin, makes a strong case for that argument. While the music and dance are performed superbly by leads and supporting players alike, Griffin’s direction never takes its eye off the storytelling and he gives us a most touching portrait of the iconic stage mother Rose and the three people caught up in her orbit. His Rose, Louise Pitre, shows us a sad woman who desperately needs the recognition of show business. While other productions of Gypsy have often introduced audiences to Rose as an eccentric but amusing stage mom, Griffin and Pitre waste no time in showing us Rose’s pain. The show’s second scene, where Rose tells her retired father the urgency of her need to leave Seattle and pursue a vaudeville career for herself and her daughters – is set in a shabby 1920’s home and plays like a scene out of Clifford Odets. When Pitre transitions from dialog into song with “Some People,” the dramatic tension continues seamlessly. In this and all the other songs, Pitre and her supporting cast make thoughtful interpretive choices throughout the show that are rooted in the imperatives of the scenes, rather than simply relying on the familiarity of standards like “Small World” and Together, Wherever We Go.” These numbers still work as show tunes but they tell us what the characters are experiencing and thinking at the moment. That above all, is what makes Gypsy a “Sondheim” show, even though Stephen Sondheim wrote only lyrics to Jule Styne’s music. Gypsy observes the creative tenet that musical numbers should advance story and character development rather than simply to entertain. In that quality, Gypsy may be the

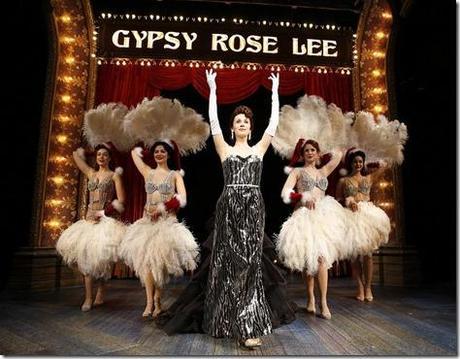

So if Gypsy is not just a great musical, but a great play, then it must follow that Rose is not a great musical theater role, but a great theater role, and Pitre may be remembered for approaching it as such. Vocally, she’s not as much of a belter as we’re used to hearing in the role. She has solid pipes, but sings in shorter phrases, with more breathing and fewer sustained notes. But what’s more important is the way she acts the songs. Whether she’s quietly seducing her paramour Herbie in “Small World” or reassuring him in “You’ll Never Get Away from Me,” she keeps us in touch with what’s driving Rose. Pitre show us Rose’s fear of being left behind and alone. While this is not a Rose you’ll necessarily want to invite over for dinner, you know where she’s coming from. Pitre and Griffin may take Rose a bit too far over the edge in the Act One closer of “Everything’s Coming Up Roses” after June and all the boys have left the vaudeville act. Here, Rose appears to have a full-on nervous breakdown. It’s astonishing, but it leaves you wondering if she’s left any room to go further for the Act Two “Rose’s Turn,” the number that’s typically performed as Rose’s collapse. Rose has calmed down quite a bit as Act Two opens – she seems resigned to the fact that the vaudeville act is finished – but this mood seems an improbably long way from the Rose we saw just before intermission. That concern aside, Pitre gives a believable Act Two journey. She goes from resigned to hopeful, as Louise gets her shot at stardom (albeit as a stripper in a Wichita burlesque house) and her “Rose’s Turn” is not so much a breakdown as a justifiable rant. While her daughters have actually achieved the stardom she sought for them – Louise as stripper Gypsy Rose Lee and June as an actress – Rose is alone and set aside. Pitre shows us Rose’s rage at the cruel irony of that.

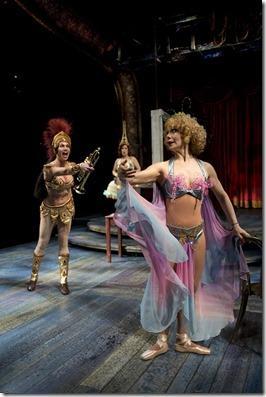

Supporting Pitre is a very solid cast, with a believable Jessica Rush as the young and tomboyish Louise who transforms into the elegant stripper Gypsy Rose Lee. A good singer who can fake sounding bad in the early scenes, she makes a cute tomboy, and then charms as the awkward teen lost in the shadow of her more talented sister June (the very funny Erin Burniston). Louise has a heart-breaking crush on the hunky “newsboy” Tulsa, played by Rhett Guter – a strong singer and dancer who also brings an edge to his ambitious character that we don’t always see. Keith Kupferer, Chicago’s go-to guy for middle-aged everyman, is pretty much a perfect Herbie – even showing some solid vocal ability in what must be one of his few, if not his first, musical theater roles. Griffin, musical director Rick Fox and choreographer Mitzi Hamilton have brought together a top-notch ensemble of child and young adult actors as the newsboys, farmboys and Hollywood blondes of Mama Rose’s various acts. Local actors John Reeger, Matt DeCaro and Marc Grapey do great work in a variety of supporting roles. And, no review of Gypsy can ignore a shout-out for the strippers in the ever-crowdpleasing number “You Gotta Get a Gimmick.” Here Griffin gets no less than Chicago’s esteemed Barbara Robertson to play Tessie Tura, who, along with Molly Callinan and Rengin Altay, deliver the goods in great style.

Seeing a show I know and enjoy so well performed on the Chicago Shakespeare’s Courtyard thrust stage reminds me how much I like the space. Gypsy, like any other backstage musical, is naturally proscenium-bound, given that so much of the action takes place on traditional stages, but. Griffin and set designer Kevin Depinet make it work on the thrust stage, with surprisingly minimal use of the proscenium. This allows us greater proximity to the actors and intimacy than we can usually get with Gypsy. The set is really little more than a proscenium arch, an overgrown and hovering pile a canopy over the stage, with small set pieces wheeled on for various scenes. The three-dimensionality of the thrust staging gives the piece a more natural, less presentational feel, and Virgil C. Johnson’s authentic 1920’s and ’30s costume designs and Melissa Veal’s wigs add to the realism of this presentation. There’s just one criticism of the design team, and it’s a big one: sound amplification that left a reverberation throughout – most noticeably in the dialog scenes. If this were the Olympics, we’d have to deduct points (maybe half a star?) for this error, but let’s presume this flaw has been fixed since opening night.

One of the strengths of Gypsy, surely, is the way book writer Arthur Laurents not only captured the bygones eras of vaudeville and burlesque, but gave the story an immediate feeling. The emotions within it are enduring, so we don’t feel distanced from the characters, even though the show’s action is happening in a different time. Beyond that, Gypsy has an edge not found in most of the “Golden Age” musicals, and a lack of the easy sentimentality that makes so many of them feel dated. It’s amazingly fresh and hard to believe it’s a 55-year-old piece. This production treats Gypsy like the enduring classic it is, deserving of mention in the same breath as the mid-century works of Miller, Williams, Inge and the like. Though Chicago Shakes is known more as a home for classics of pre-modern drama, it feels right at home here.

Rating: ★★★★

Gypsy continues through March 23rd at Chicago Shakespeare at Navy Pier, 800 E. Grand (map), with performances Tuesdays at 7:30pm, Wednesdays at 1pm and 7:30pm, Thursdays-Fridays at 7:30pm, Saturdays 3pm and 8pm, Sundays 2pm. Tickets are $48-$88, and are available by phone (312-595-5600) or online through their website (check for half-price tickets at Goldstar.com). More information at ChicagoShakes.com. (Running time: 2 hours 40 minutes, includes an intermission)

Photos by Michael Brosilow

artists

cast

Louise Pitre (Rose), Jessica Rush (Louise), Keith Kupferer (Herbie), Erin Burniston (June), Rhett Guter (Tulsa), Brandon Haagenson (L.A.), Adam Fane (Angie), Joseph Sammour (Yonkers), Barbara E. Robertson (Tessie Tura), Molly Callinan (Mazeppa), Rengin Altay (Electra), Marc Grapey (Uncle Jocko, Cigar, Phil), John Reeger (Pop, Mr. Goldstone, Minsky’s Announcer, Bourgeron-Cochon), Matt DeCaro (Weber, Kringelein, Pastey), Cullen J. Rogers (Georgie, stage hand), Moira Hughes, Katherine Mallen Kupferer (balloon girls), Benedict Santos Schwegel (Ulysses, newsboy), Emily Leahy (Baby June), Caroline Heffernan (Young Louise), Betsey Farrar (waitress, Caroline, Ethel Mae), Dana Parker (Caroline, Dolores, Renee), Kelly Anne Krauter (Marjorie Mae, stage hand), Maddie DePorter (showgirl, stage hand), Alex Grace Paul, Lauren Roesner (showgirls), Nate Becker, Killian Hughes (newsboys), Jared Rein (stage hand).

behind the scenes

Gary Griffin (director). Kevin Depinet (scenic design), Virgil C. Johnson (costume design), Philip S. Rosenberg (lighting design), Lindsay JoneRay Nardelli, Dan Head (sound design), Melissa Veal (wig, make-up design), Mitzi Hamilton (choreography), Rick Fox (music direction, additional orchestrations), Bob Mason (casting), Stephanie Klapper (New York casting), Deborah Acker (production stage manager), Michael Brosilow (photos)

14-0221