Freud’s Last Session

Written by Mark St. Germain

Directed by Tyler Marchant

at Mercury Theater, 3745 N. Southport (map)

thru June 3 | tickets: $45-$55 | more info

Check for half-price tickets

Read entire review

An smartly entertaining dose of therapy from Freud himself!

Carolyn Rossi Copeland, Robert Stillman, and Jack Thomas presents

Freud’s Last Session

Review by Clint May

Any debate between a believer and a non-believer (about anything, anywhere, at anytime) is probably going to remain frustratingly agnostic. There’s an evolutionary (already I have to use an incendiary term) reason for this called the ‘argumentative theory of reasoning’ and it does a lot to explain how our culture gets more, not less, polarized as time passes. Like the old fable of the wind vs. the sun, blowing harder only makes people draw their beliefs to themselves ever tighter, sometimes to the point of strangulation. With ever escalating and increasingly absurd arguments being bantered about and toted as fact—remember when Stephen Colbert coined the word ‘truthiness’?—it’s no wonder Mark St. Germain thought it was time to write something that said, “Let’s remember, we’re all still human here no matter which side you’re on.” Freud’s Last Session creates a fiction to bring two paragons of the 20th century together, not as a means of actually answering any of the questions it poses, but as a didactic illustration of the importance of a continuing and civilized debate.

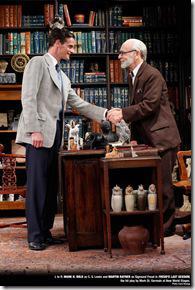

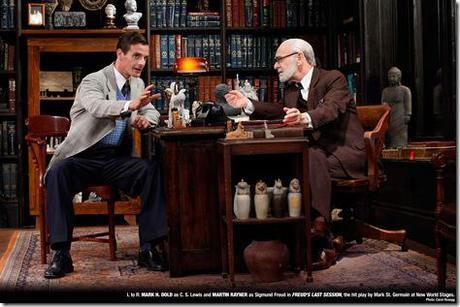

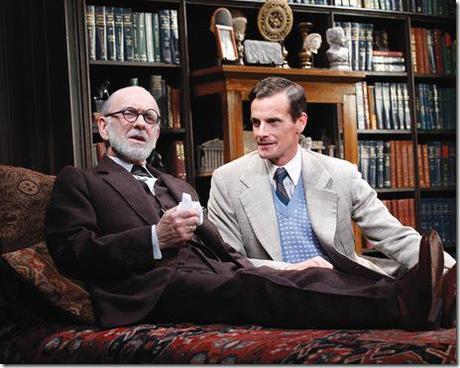

Set on the day Great Britain declared war on Germany and just a few weeks before Freud’s requested euthanasia, it begins with C. S. Lewis arriving at Freud’s study seemingly to be chastised for including a caricature of psychoanalytic hubris in his recent novel. Lewis (Mark H. Dold) has relatively recently begun his path from former atheist to one of the most revered of Christian apologists. Freud (Martin Rayner) is already the Sigmund of legend with his now famous glasses, beard and cigar as firmly entrenched in pop culture as Einstein’s hair. Dying from oral cancer but lacking none of his dryly dark humor and incisively analytical mind, Freud is intrigued for one last chance to study how an avowed atheist “angry at God for not existing” could become a true believer. Forty-one year old Lewis has the proud bearing of a knight with a geas in contrast to Freud’s desire for pure scientific rigor. Both are big intellects, but neither can completely be free of the purely emotional desire to protect the worldview they’ve created for themselves. Sparks occasionally fly, but on the whole their discussions about God and sex and meaning remain respectful, punctuated with tension from air raid sirens and radio announcements that bring their discussion into the larger world of impending doom.

The arguments on display, perhaps by necessity, never get much deeper than a Philosophy 101 class. Syllogisms from Epicurus’ problem of evil to Lewis’ own version of the “Liar, lunatic or Lord” argument (later just “Lewis’ Trilemma”) are trotted out and pitted against Freud’s own psychoanalysis, often to quite humorous effect. Humor plays an essential role, diffusing tension and building the necessary rapport for these two mannered gentlemen. In the bright light of 80+ years of review, we’ve had a lot of philosophers and scientists weigh in on these topics. The trilemma was just a false dilemma and psychoanalysis has fallen out of favor. Both men have been become legends beyond the actual validity of their arguments, not unlike Ptolemy after Copernicus or Newton after Einstein. They held incommensurable (and unprovable) viewpoints, but as imagined by St. Germain, they’re able to view each other as people, not positions. Fallible and frail but not unwilling to discuss the eternal topics, Freud and Lewis’s mostly convivial interactions recall Mark Vonnegut’s immortal words, “We’re here to get each other through this thing, whatever it is.” Compassion wins over controversy in the end.

Rayner inhabits a fantastic Freud that is at times cantankerous but also somewhat avuncular. The cancer that consumes his mouth brings him conveniently down from history’s pedestal, and allows Dold’s Lewis (also a delight to behold, straddling the fine line of zealot and intellect) to connect on a human level. St. Germain’s script at times applies psychoanalysis to itself with an unnaturalistic self-awareness of its humor and acknowledged inability to actually answer any important questions in a short amount of time. It won the Off Broadway Alliance award in 2011 for Best Play, and had it dug deeper into the questions it purports to be boldly tackling, it might have been the play of the decade.

The Sun, it turns out, actually does orbit the Earth—the barycenter is just so far inside the Sun it’s true only in a purely semantic sense. Thus Copernicus himself would have to budge a little after Newton. Watching these two spare is like watching two massive bodies attempt to alter each other’s orbits. Freud’s incredibly small deference to Lewis in the form of the acknowledging the importance of music and feeling in beliefs is like watching a massive celestial body shift one degree. It’s disappointing to see no such deference from Lewis to rationality, though one could argue that as an apologist, his stated goal was to bring rationality to faith. The fundamentals don’t change, but respect and the ability to listen remains. Change, even when it seems a sudden lighting bolt on the road to Damascus, is actually the result of the slow accretion of time and persuasion. It’s tantalizing to think what this production could have been had it been expanded to include a Freud in his prime and a pre-conversion Lewis.

Taken as it is, Freud’s Last Session is a simple, luminous one-act that will do more to engender respect for titanic differences than it will to spark any new revelations concerning God, sex and man’s place in the cosmos (conversations about them after notwithstanding). The tough questions need tough people, and in our age of information wherein our memories are being offloaded to Google and propaganda becomes more pernicious, critical thinking is all the more important. Viewpoints will come and go, and trepidation on the road to awareness is essential to hold off the lack of intellectual rigor that creates a seemingly self-contained world that consumes the unwary. As luminaries with their own flawed logic, Lewis and Freud’s parlay is a gentle parable to remind the world to have some humility, for today’s truths are inevitably tomorrows mythologies.

Rating: ★★★★

Freud’s Last Session continues through June 3rd at Mercury Theater Chicago, 3745 N. Southport (map), with performances Wednesdays 2pm & 7:30pm, Thursdays 7:30pm, Fridays 8pm, Saturdays 2pm & 8pm, Sundays 1pm & 5pm. Tickets are $45-$55, and are available by phone (773-325-1700) or online at vendini.com (check for half-price tickets at Goldstar.com). More information at MercuryTheaterChicago.com. (Running time: 85 minutes with no intermission)

All photos by Carol Rosegg